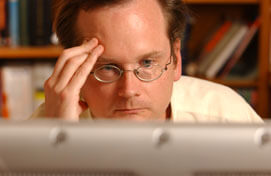

Attracting the Unabomber. While overselling behavior modification

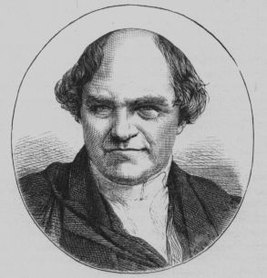

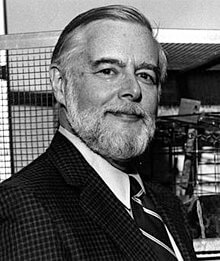

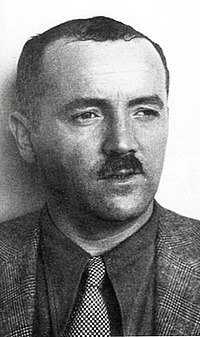

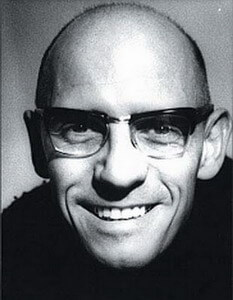

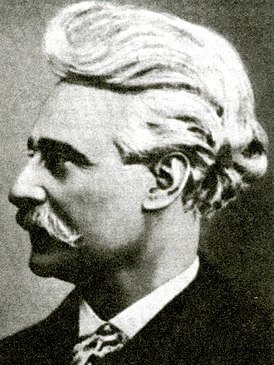

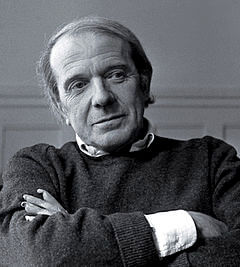

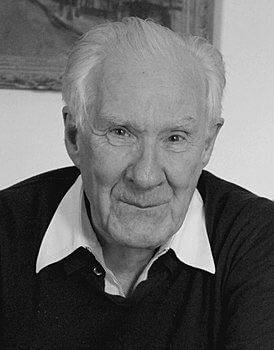

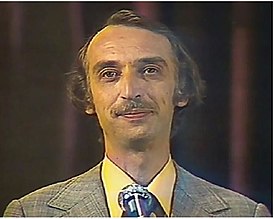

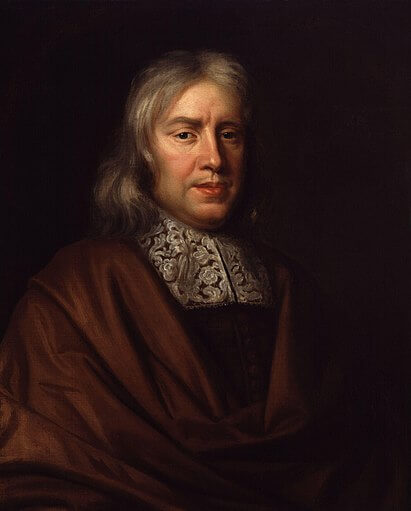

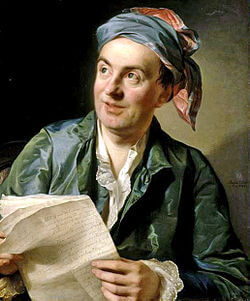

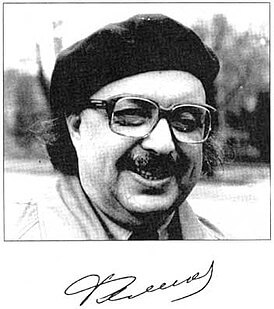

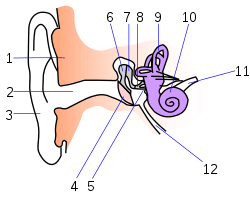

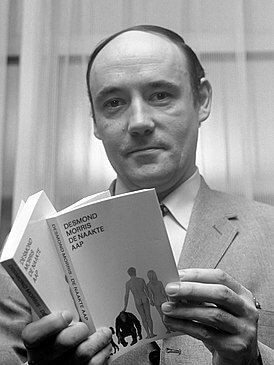

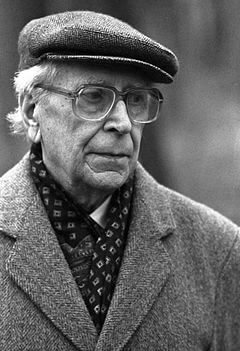

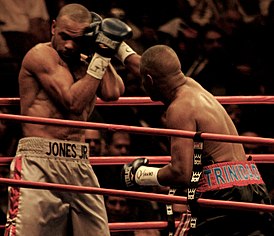

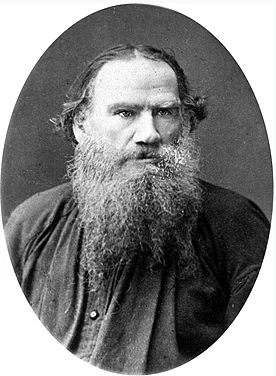

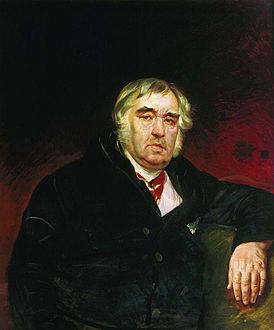

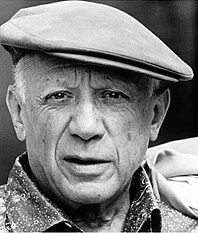

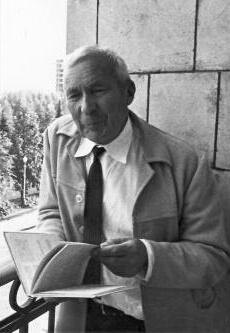

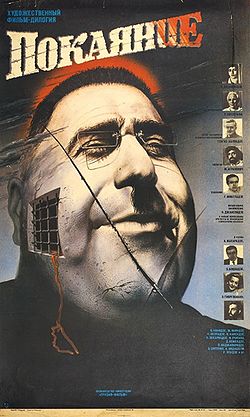

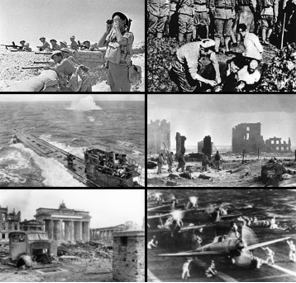

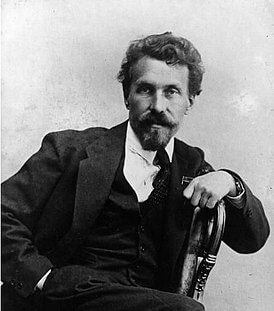

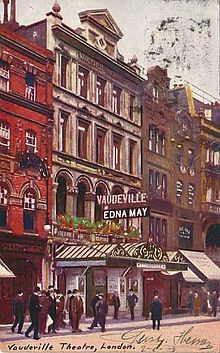

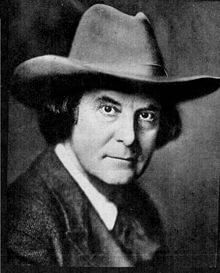

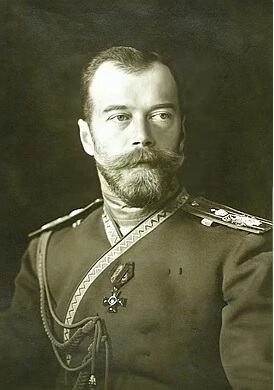

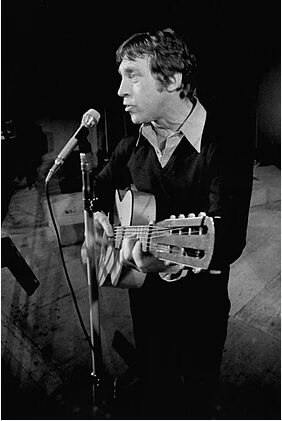

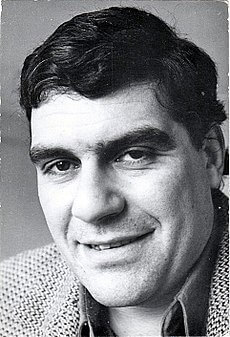

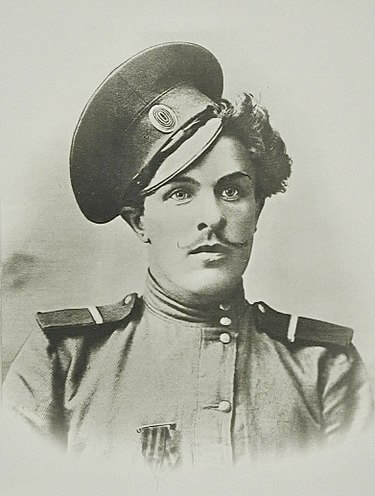

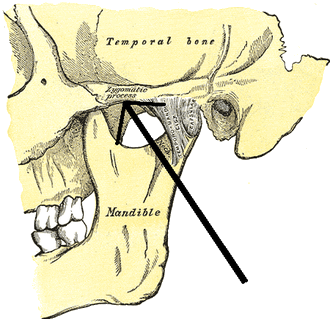

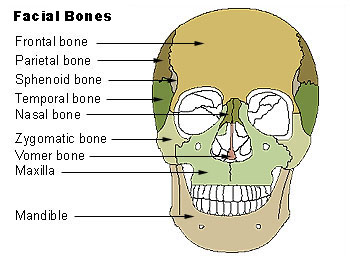

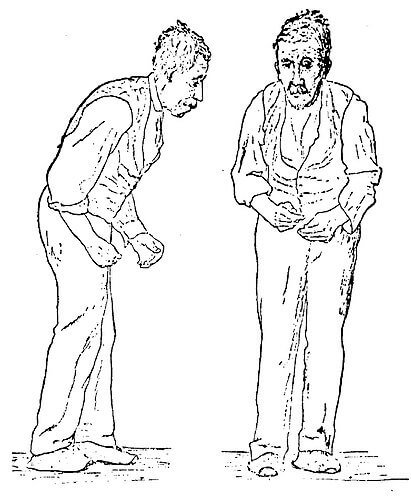

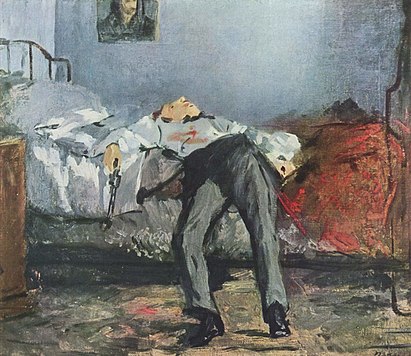

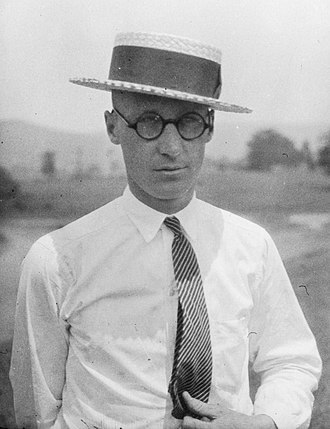

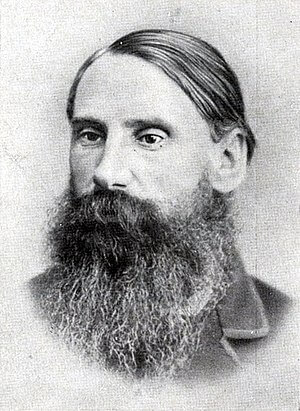

The assassination attemptOn November 15, 1985, James McConnell became the victim of an assassination attempt by a serial bomber who is known to the media as the Unabomber because his earlier victims included professors and executives of airlines. At this writing, a man suspected of being the Unabomber has been arrested. Fortunately, McConnell was not killed, but his hearing was impaired by the soundof the blast. As far as I am able to determine, this sad episode marked the first time in the history of psychology that the murder of a psychologist was attempted, by an individual who did not know his victim, for the sole reason that the would-be assassin found the psychologist’s ideas offensive. McConnell was the intended victim of the bombing, but the Unabomber’s real target was applied psychology, specifically behavior modification. Unfortunately, the Unabomber selects his targets from those scientists who popularize technology with bold, simplified rhetoric that includes sweeping predictions about how technology will change society. McConnell wrote two magazine articles about behavior modification, Psychoanalysis Must Go for Esquire and Criminals Can Be Brainwashed Now for Psychology Today, either of which could have caught the Unabomber’s eye. The Unabomber targeted McConnell because he popularized behavior modification.

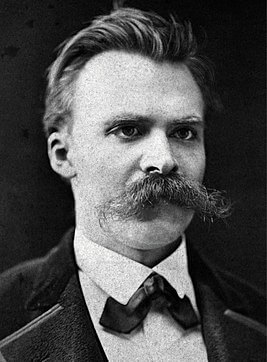

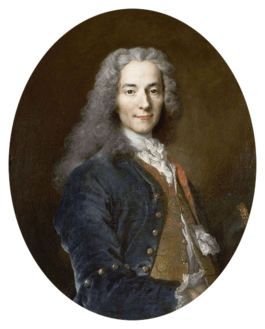

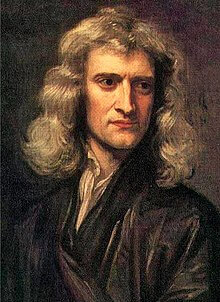

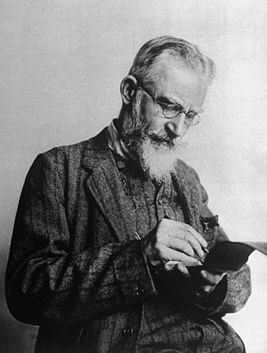

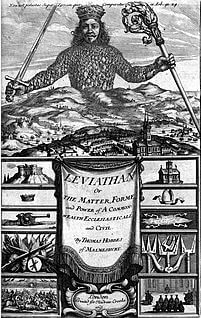

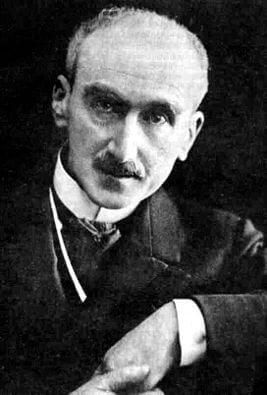

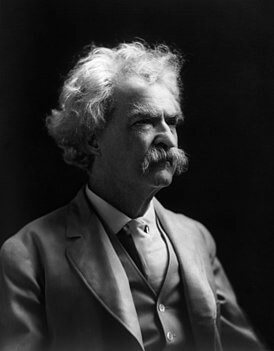

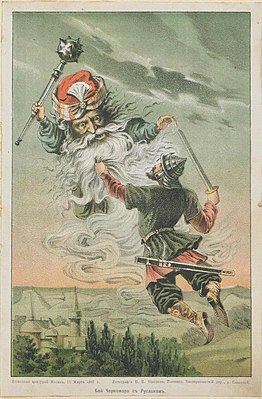

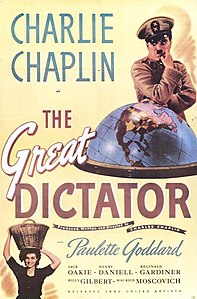

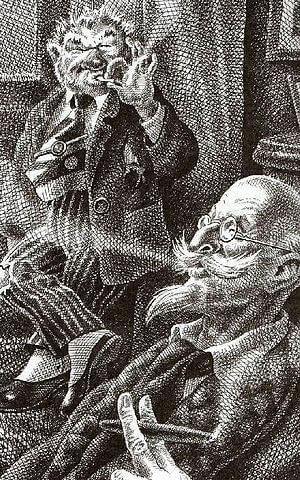

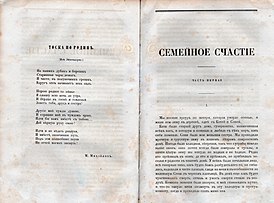

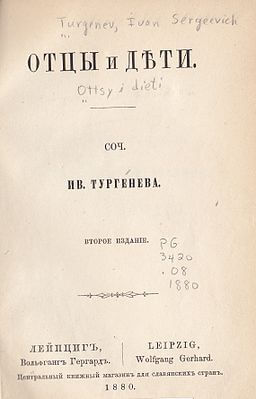

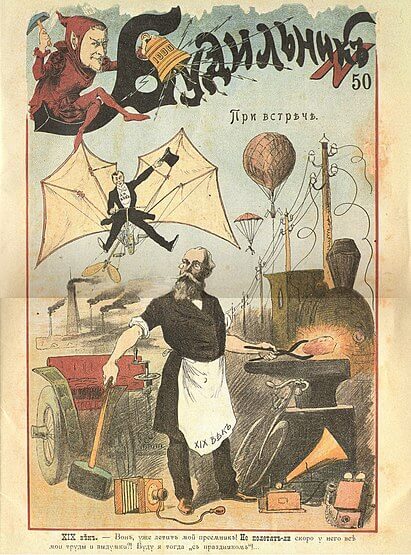

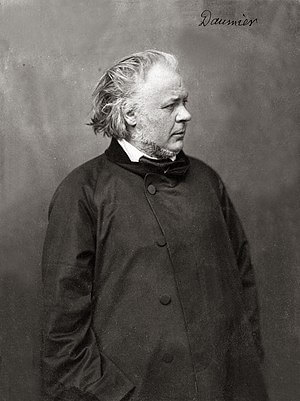

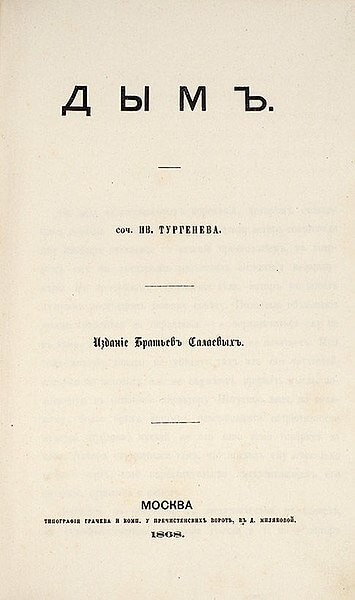

Overpopularizing behavior modificationAfter McConnell’s planarian research program collapsed, he turned to B. F. Skinner‘s brand of behavior modification, but his contributions to the field were not distinguished. Much as Thomas Huxley was a bulldog for Darwin‘s theory of evolution, James McConnell used his considerable rhetorical and public relations skills to popularize behavior modification. Just as John Watson oversold behaviorism during the 1920s in the media, James McConnell wrote articles for the popular press that oversold behaviorism during the 1960s. McConnell, who wrote that the entire history of scientific psychology may be viewed as a continuing search for better controls, failed to generalize this truism from planarian learning to behavior modification. McConnell naively believed that the application of a behavioristic conception of reward and punishment would solve the social problems of crime and mental illness. He failed to recognize that the evaluation of a behavioral modification program required control groups. Esquire tried to be funny about the 1960s, so the magazine provided an ideal forum for McConnell. In 1968, when its 35th anniversary coincided with political assassinations, Esquire commissioned a set of articles around the theme Salvaging the Twentieth Century. McConnell was commissioned to write not only about what was wrong with psychology, but also about what was worth salvaging. McConnell’s piece was Psychoanalysis Must Go, an article accompanied by a drawing in which Freud, his diploma, and his couch were caught in free fall against the background of a multistory, dingy, office building. After an unsupported, bald assertion that psychoanalysis doesn’t really help the patient at all, McConnell went on to predict that behavior modification would eliminate the need for mental hospitals and prisons. His article concluded with the following predictions: Mental hospitals as such will probably disappear in the next twenty years or so… Indeed, we should be able to discover methods of retraining criminals that will be so powerful we can guarantee that, once released, the prisoners will be most unlikely to commit a crime again. McConnell, 1968, p. 287

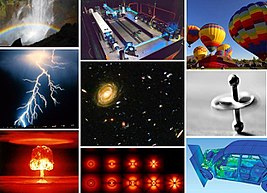

However, history shows that behavior modification led to the disappearance of neither crime nor mental illness. By overselling behavior modification as a panacea for crime, McConnell helped plant the seeds for the public disillusionment with psychological interventions that haunts our profession today. McConnell did not realize that his overoptimism set a trap for the next generation of applied psychologists. Today, a social critic could say that these programs were not as effective as promised. Brown demonstrated that the promoters of early applied psychology often drew metaphors from more prestigious professions such as medicine, as when the early promoters of IQ tests compared the IQ tests with thermometers. Because physics had high prestige from the nuclear weapons developed during World War II and because McConnell also knew that scary stories made news, he combined fear and the metaphor of the atomic bomb as a public relations tool to sell behavior modification when he wrote the following: The techniques of behavioral control make even the hydrogen bomb look like a child’s toy. McConnell, 1970, p. 74

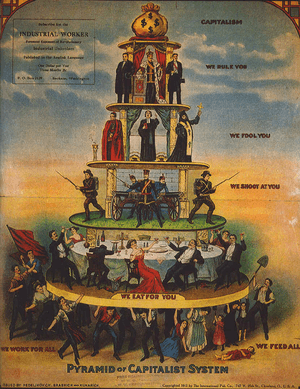

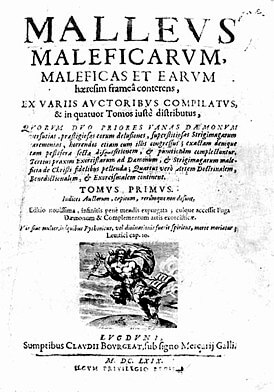

In Psychoanalysis Must Go, McConnell frightened his readers with a vision of an ascendant behavioral revolution so powerful and so pervasive it’s doubtful that your life will ever be quite the same again. Totalitarian, antidemocratic threats also scared the American public. In a book devoted to the cultural significance of American psychology following World War II, Herman noted that No science poked more holes in democratic ideals than psychology. p. 23.

McConnell knew that he could scare his readers by comparing behavioral engineers with an Orwellian vision of a totalitarian state. Therefore, he ended his editorial in Psychology Today with a vision of a behavioral engineer with a license to redesign American society along anticivil liberties principles: Today’s behavioral psychologists are the architects and engineers of the Brave New World. With his most provocative statement, McConnell wove prophecy, behavior modification, and antidemocratic rhetoric into a very scary, antidemocratic scenario: I believe the day has come when we can.., gain almost absolute control over an individual’s behavior.., and there is no reason to believe you should have the right to refuse to acquire a new personality if your old one is antisocial. McConnell, 1970, p. 74.

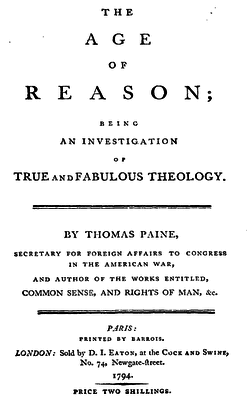

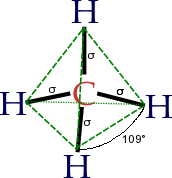

McConnell lived in a period in which the popular culture was saturated with revolutionary rhetoric. In the United States during the 1960s, there was rhetoric of a sexual revolution, a Black power revolution, a revolution in the culture of popular music called rock’n’roll, and the Vietnam War produced calls for a political revolution. Therefore, it is not surprising that McConnell, who was closely attuned to popular culture, would adopt revolutionary rhetoric to advance his views. As a Skinnerian behaviorist, McConnell could honestly write that Today’s revolutionary concept is that man’s behavior can be studied, and explained, in objective terms without any necessary reference to supernatural or spiritual or mentalistic entities. ‘Mind’… is as useless an explanatory concept to today’s scientific psychologist as the mythical element ‘phlogiston’ that chemists once believed caused all fires. McConnell, 1968, p. 176

McConnell caught a high-water mark of behaviorism, just before its ebb and the rise of modern cognitive psychology.

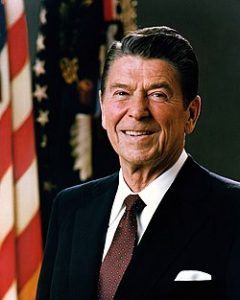

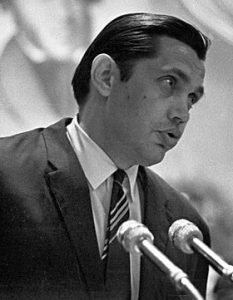

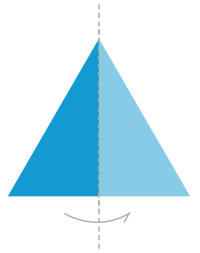

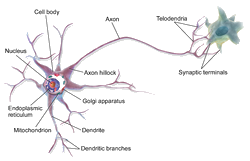

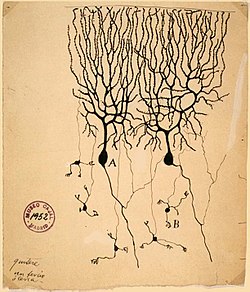

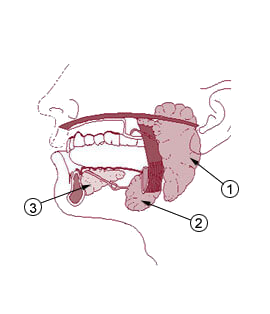

Conclusion: some historical lessons for today from the 1960sThe history of invertebrate learning illustrates how ideas are assimilated by the scientific community. During the 1930s, invertebrates were considered little robots, guided by instincts, in which the ability to learn was, at most, ephemeral. During the 1960s, James McConnell, a creative, charismatic comparative psychologist, used the media and revolutionary rhetoric from the counterculture to glamorize planarian learning and to attack the view of the scientific establishment that invertebrates could not learn. McConnell used a Pavlovian conditioning paradigm. When the adequacy of the early data was challenged by critics, McConnell and others caught up in the espirit de corps for planarian learning introduced control groups that are still used today for Pavlovian conditioning. Although his memory-transfer paradigm for studying the biochemical basis of memory was a failure, McConnell has not received the credit he deserves for establishing invertebrate learning. Today, invertebrate learning is so well established that citations to the earlier work are no longer considered necessary. Replication and peer review worked well for evaluating McConnell’s scientific ideas. Unfortunately, peer review does not provide a mechanism for regulating the popularization of psychological ideas by the media because journalists and the producers of television shows are not experts on the science. Because psychologists have a First Amendment right to express their views on psychological topics as they see fit, the problem of how to popularize psychology without misleading the public does not have a simple solution. As a celebrity-scientist, McConnell presented the mass audience of television, radio, and the popular press with a mixture of basic scientific information about Pavlovian conditioning in invertebrates, futuristic predictions about a memory pill, and entertainment. As a science writer, McConnell promised the public more than he could deliver. After the collapse of the planarian project, McConnell became a shill for B. E Skinner’s brand of behavior modification. A behavioral engineer could guarantee that a suitably retrained prisoner with a new personality would never commi t a crime. Ultimately, McConnell became more adept at publicity than in providing original contributions to the science. It appears that McConnell’s public relations efforts on behalf of behavior modification led to an assassination attempt on him by the Unabomber, a Luddite opposed to behavioral engineering. McConnell deserves to be remembered not only for his scientific creativity, but also because he was one of our field’s great popular writers. The public expects prophecy from its scientists. However, McConnell did pay a cost. He provided the public with the prophecy they expected and received the fleeting fame that comes from the publicity of the moment, but at the price of professional ostracism. Fidelity to the peer-reviewed literature is proposed as an ethical standard for evaluating coverage of psychological topics for and by the media.

ReferencesAbramson, C.I. A primer of invertebrate learning: The behavioral perspective. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Allport, S. Explorers of the black box: The search for the cellular basis of memory. New York: Norton.

Animal life: Strangest of tails. Newsweek, 54, p. 110.

ABaxter, R., & Kimmel, H.D. Conditioning and extinction in the planarian. American Journal of Psychology, 76, 665-669.

ABeach, E A. The snark was a boojum. American Psychologist, 5, 115 — 124.

ABenjamin, L.T. Why don’t they understand us? A history of psychology’s public image. American Psychologist, 41, 941-946.

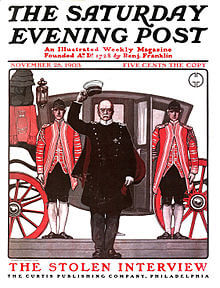

ABird, J. The worm learns. Saturday Evening Post, 237, pp. 66 — 67.

Bitterman, M.E. Critical commentary. In W. C. Corning, J.A. Dyal, & A. O. D. Willows, Invertebrate learning. New York: Plenum.

Block, R. A., & McConnell, J. V.. Classically conditioned discrimination in the planarian, Dugesia dorotocephala. Nature, 215, 1465 — 1467.

Bomber links an end of killings to his manifesto. The New York Times, p. 1.

Brown, J. The definition of a profession: The authority of metaphor in the history of intelligence testing, 1890-1930. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Carew, T. J., Walters, E. T., & Kandel, E. R. Classical conditioning in a simple withdrawal reflex in Aplysia californica. The Journal of Neuroscience, 12, 1426 — 1437.

Cmiel, K. The politics of civility. In D. C. Farber, The sixties: From memory to history. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Collins, H., & Pinch, T.. The Golem: What everyone should know about science. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Cordaro, L., & Ison, J. R. Psychology of the scientist: Observer bias in classical conditioning of the planarian. Psychological Reports, 13, 787 — 789.

DeZazzo, J., & Tully, T. Dissection of memory formation: From behavioral pharmacology to molecular genetics. Trends of Neuroscience, 18, 212 — 218.

Donegan, N.H., & Thompson, R.E. The search for the engram. In J. L. Martinez & R. E Kesner, Learning and memory: A biological view. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Farber, D.C.. The sixties: From memory to history. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Finger, S. Origins of neuroscience. New York: Oxford University Press.

Herman, E. The romance of American psychology. Political culture in the age of experts. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hilgard, E.R. Theories of learning. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Jacobson, A.L., Horowitz, S.D., & Fried, C. Classical conditioning, pseudoconditioning, or sensitization in the planarian. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 64, 73 — 79.

Jensen, D.D. Paramecia, planaria, pseudo-learning. Animal Behavior Supplement, 1, 9.

Koestler, A. Introduction: Behold the lowly worm. In J. V. McConnell, The worm returns: The best from The Worm Runner’s Digest. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall..

Krasne, F.B., & Glanzman, D.L. What we can learn from invertebrate learning. In J.T. Spence, J.M. Darley, & D.J. Foss, Annual review of psychology. Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews Inc.

Maler, N.R.F., & Schneirla, T.C. Principles of animal psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill.

McConnell, J.V. The after-effects of rotation of the visual environment. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Texas, Austin.

McConnell, J.V. Worms and things. The Worm Runner’s Digest, 1,1.

McConnell, J.V. Worms and things. The Worm Runner’s Digest, 2, 1 — 3.

McConnell, J.V. Worms and things. The Worm Runner’s Digest, 3, 1 — 3.

McConnell, J.V. Worms and things. The Worm Runner’s Digest, 3, 153 — 156.

McConnell, J.V. Memory transfer through cannibalism in planarians. Journal of Neuropsychiatry, 42 — 48.

McConnell, J.V. Cannibalism and memory in flatworms. New Scientist, 21, 465 — 468.

McConnell, J.V. Learning theory. In J.V. McConnell, The worm returns: The best from The Worm Runner’s Digest. Englewood Cliffs, N J: Prentice-Hall.

McConnell, J.V. Comparative physiology: Learning in invertebrates. In V. E. Hall, A.C. Giese, & R.R. Sonnenschein, Annual review of physiology, Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews, Inc.

McConnell, J.V. A manual of psychological experimentation on planarians. Ann Arbor, MI: The Worm Runners Digest.

McConnell, J.V. Worms and things. The Worm Runner’s Digest, 9, 11 — 8.

McConnell, J.V. Psychoanalysis must go. Esquire, 70, pp. 176, 279 — 280, 283 — 287.

McConnell, J.V. Confessions of a scientific humorist. Impact of Science on Society, 19, 241 — 252.

McConnell, J.V. Criminals can be brainwashed now. Psychology Today, 13, pp. 14, 16, 18, 74.

McConnell, J.V. Worms and things. The Worm Runner’s Digest, 15, 1 — 3.

McConnell, J.V. Understanding human behavior New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

McConnell, J.V. Worms and things. The Worm Runner’s Digest, 16, 1 — 3.

McConnell, J.V. Confessions of a textbook writer. American Psychologist, 33, 159 — 169.

McConnell, J.V. Worms and things. The Worm Runner’s Digest, 21, 1 — 2.

McConnell, J.V. Understanding human behaviorNew York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

McConnell, J.V. Hear! Hear! Fanfare, 10, 282 — 288.

McConnell, J.V., Jacobson, A.L., & Kimble, D.P. Che effects of regeneration upon retention of a conditioned response in the planarian. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 52, 1 — 5.

McConnell, J.V., Jacobson, R., & Maynard, D.M. Parent retention of a conditioned response following total regeneration in the planarian. American Psychologist, 14, 410.

McConnell, J.V., & Shelby, J.M. PMemory transfer experiments in invertebrates. In G. Ungar Molecular mechanisms in memory and learning. New York: Plenum Press.

Moskowitz, I. School for worms: Interview with James V. McConnell. The Steve Allen Show. Los Angeles: Curtis Circulation.

Polsgrove, C. It wasn’t pretty folks, but didn’t we have fun? Esquire in the sixties. New York: Norton.

Rose, S. The making of memory. New York: Anchor Press/Doubleday.

Serial bomber sent letters before package blast. The New York Times, p. 1.

Service, R.E. Will a new type of drug make memory-making easier? Science, 266, 218 — 219.

Thompson, R., & McConnell, J. Classical conditioning in the planarian, Dugesia dorotocephala. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 48, 65 — 68.

Thorne, B.M. WRobert Thompson: Karl Lashley’s heir? Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 31, 129 — 136.

Todd, J.T., Dewsbury, D.A., Logue, A.W., & Dryden, N.A Appendix: John B. Watson: A bibliography of published works. In Todd J. T. & E. K. Morris Modern perspectives on John B. Watson and classical behaviorism. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Travis, D. On the construction of creativity: The memory transfer phenomenon and the importance of being earnest. In K. D. Knorr, R. Krohn, & R. Whitley The social process of scientific investigation, sociology of the sciences Boston: D. Reidel.

Travis, G. D. L. Replicating replication? Aspects of the social construction of learning in planarian worms. Social Studies of Science 11, 11 — 32. | Smile, says U psychologist; It’s good for youContinuation. To top The learning goes even faster if one can make a videotape of the process. Then the person has a very objective record of how frequently he smiles — as well as how others respond to those smiles, says McConnell.

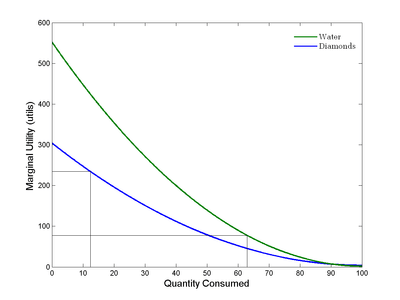

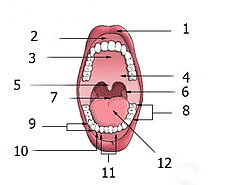

Learning seldom occurs unless we get feedback, either from monitoring our own actions, or through the responses of people around us. The two kinds of feedback are rewards and punishment.

Reward tend to increase our motivation, security and sense of accomplishment. But punishment tends to interrupt behavior, suppress emotions and make us feel negativity toward punisher. Frowns, McConnell says, are a form a punishment.

FROWNS, LIKE smiles, affect both the sender and receiver. Studies show that medical doctors who are frowning and critical toward their patients experience twice as many malpractice suits as doctor who are smiling and encouraging, McConnell states. Also, for some time I have worked with parents of delinquent children. More than 80% of these parents are punitive non-smilers. The other parents may smile, but the spend little time with their kids anyhow. I have never met a delsnquent’s parent who was warm, encouraging and smiling!

Go to a cocktail party and watch who is attracted to whom. People who smile draw more attention. They are better like and are perceived as being more friendly.

Frowns are a type psychopollution that are as deadly as smoke fumes or mercury in drinking water, McConnell declares. One can kill the spirit more easily than the body, I suspect. We legislate against polluted air and water, maybe we ought to legislate for more smiling, to improve mental health!

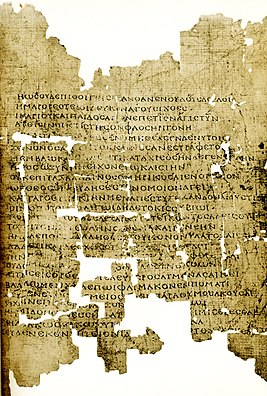

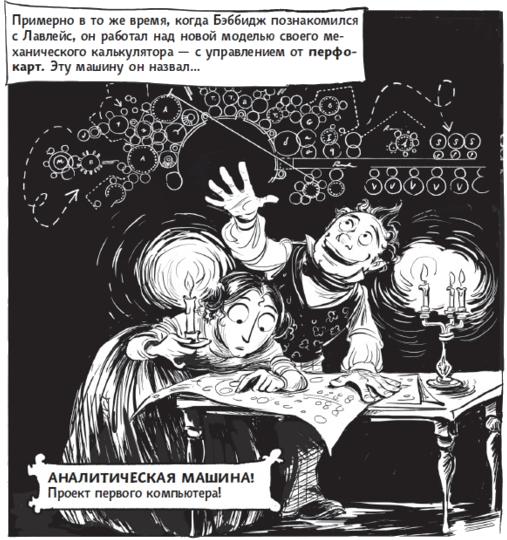

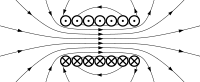

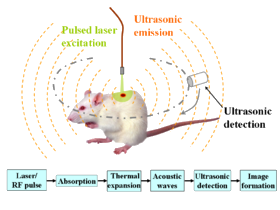

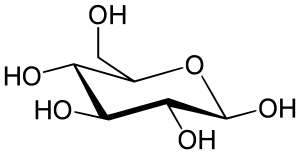

From the article by Georges Chapouthier From the search for a molecular code of memory to the role of neurotransmitters: A historical perspectiveThe question of memory transfers The third method, called memory transfers, was more likely to demonstrate specific effects. If trained brain extracts were in fact able to transfer memorized pieces of information from one trained animal to another, then a strong argument could thus be given for the existence of ’memory molecules’. This dramatic method does, however, come up against several methodological objections that will not be reviewed extensively.

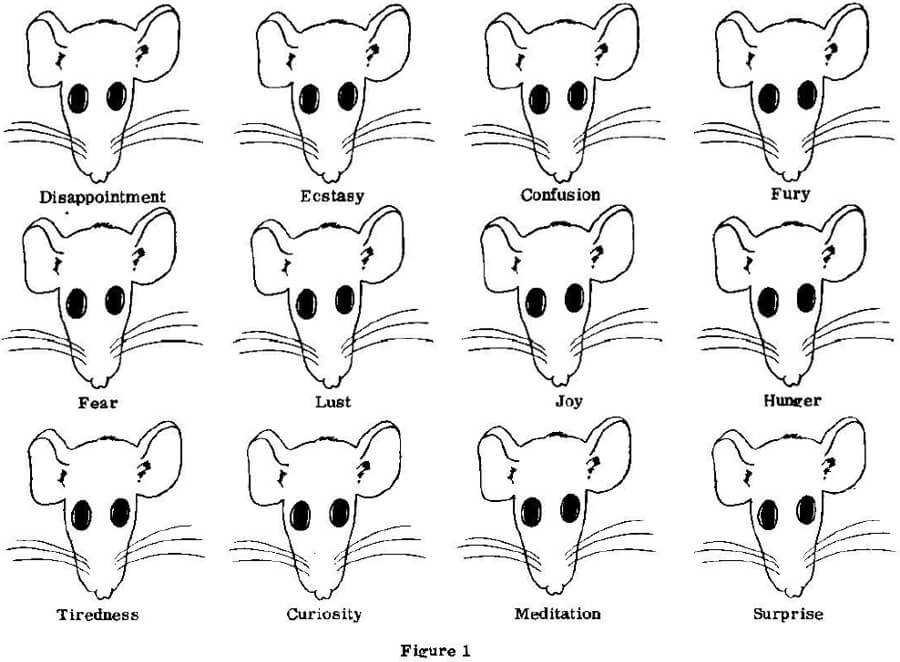

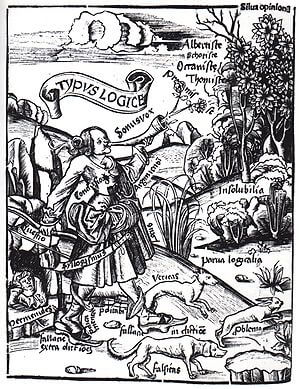

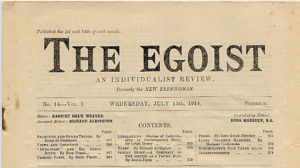

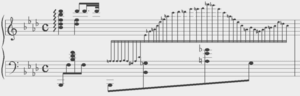

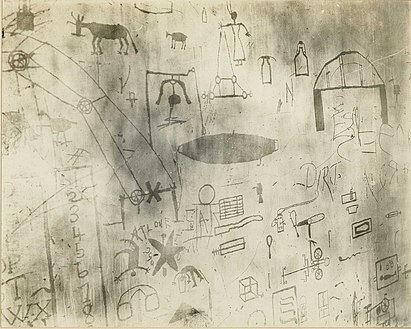

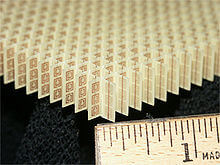

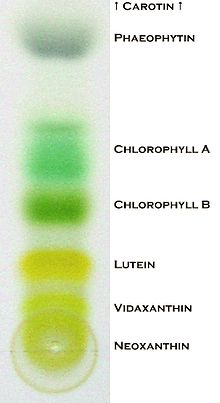

A first attempt to use this method was made by McConnell and his research group on planarian worms, and will be presented below. Several reports can also be found in McConnell’s journal, entitled The Worm Runner’s Digest, kept from 1959 to 1979. The journal originally began as a laboratory documentary record, mixing serious scientific reports with lab jokes. In October 1964, the diary turned into a more lavish publication. In 1967, one half kept the name of The Worm Runner’s Digest and continued to publish humorous articles, while the other half took the more serious title of the Journal of Biological Psychology. The two halves combined to form a whole, and the journal could be turned upside down and read from both sides!

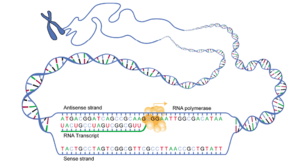

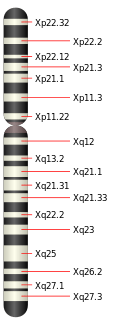

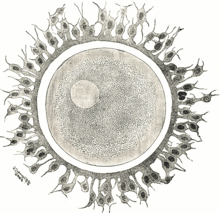

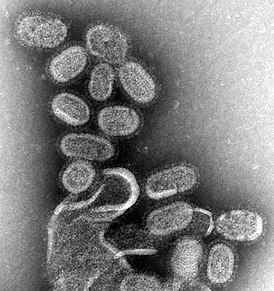

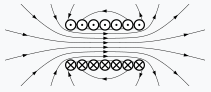

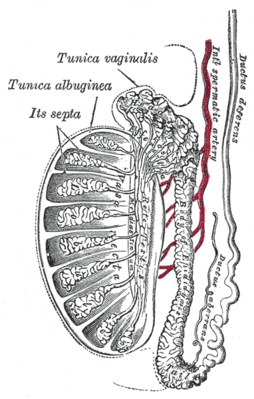

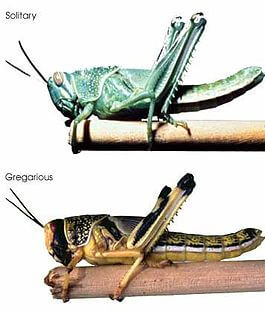

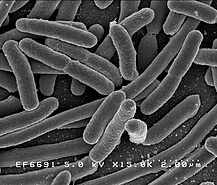

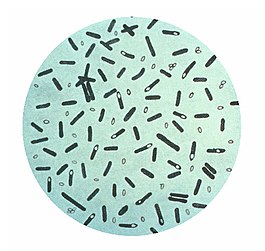

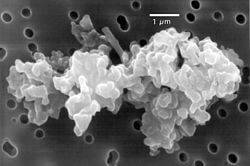

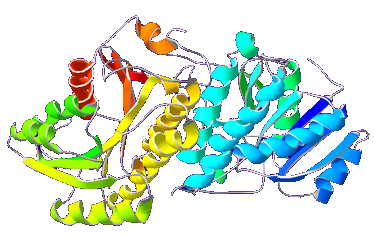

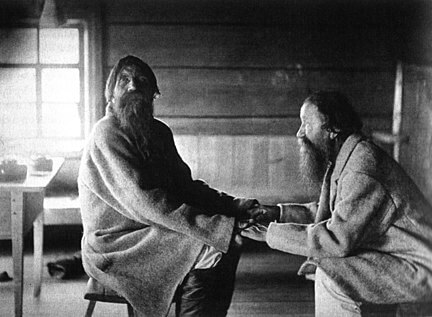

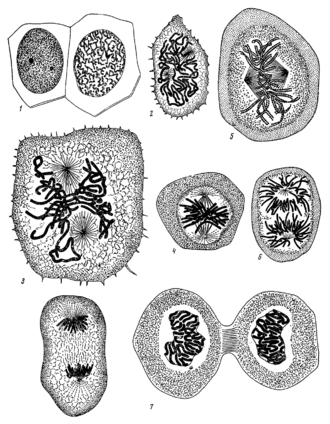

Planarian worms are capable of complete regeneration if cut into two or more pieces. They can also assimilate into their body ingested pieces of other animals of the same species, without major digestion; the phenomenon is similar to grafting, but is known as cannibalism. McConnell et al. claimed to have taught planaria several conditioning procedures. The research group argued that the conditioning remained after regeneration and using the cannibalism procedure could be transmitted from one trained animal to another one. The authors believed, however, that whereas regeneration could occur in water containing RNAse, the memory of this conditioning disappeared. Yet, RNA directly extracted from trained planarians seemed to be capable of ’transferring’ the acquired conditioning to naive animals. From all these data, McConnell’s group concluded that the memory of planarians was coded in RNA molecules and that these memory molecules could occasionally be transmitted from one worm to another.

As is often the case in work involving animal behavior, several biases were subsequently found in the studies and tended to undermine the provocative conclusions. The conditioning of planarians appears to be a more complex phenomenon than already thought. Such conditioning is often restricted to partial responses, far from the 100% responses of higher animals, and sometimes develops into a strange phase known as rejection of the reinforced goal. Yet the cannibalism itself was shown to modify certain behavioral responses in a way that Could appear to be conditioning — for example, hungry planarians, as could be the case for cannibalistic planarians, become more sensitive to light, which also happened to be one of the responses for conditioning chosen by McConnell et al.

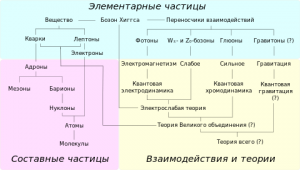

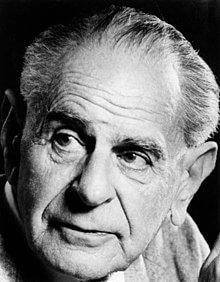

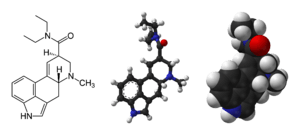

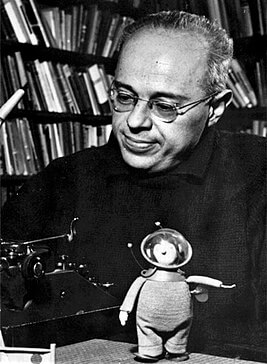

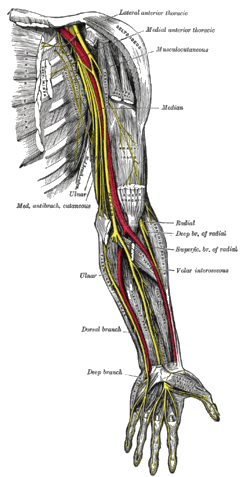

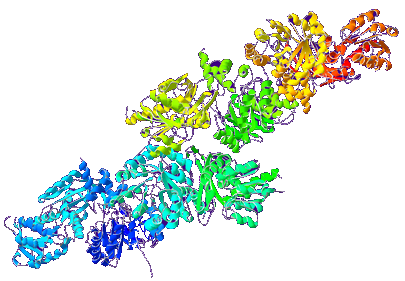

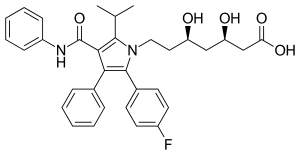

These pioneer studies had induced similar results in vertebrates. In 1965, a number of research groups published data suggesting that it was possible to transfer memorized information by implanting brain extracts from donor rats into recipient rats. With the exception of Ungar, all the authors followed McConnell’s assumptions and used RNA extracts, but it was shown later that RNA could not be the agent responsible for the behavioral changes observed. Although the RNA extracts were certainly active, the effects on the planarians were probably caused by impurities in the extracts. This aspect was clearly demonstrated by the outstanding work conducted by Georges Ungar. Ungar showed that the agents responsible for the change were probably peptides, namely small proteins. In fact, the apparent memory transfer effects disappeared with either purified RNA or brain extracts treated with chymotrypsin, an enzyme able to digest proteins. Ungar then isolated from rat brain a cerebral peptide that he named scotophobin, which seemed to transfer learned fear of the dark when administered to recipient mice. When chemically synthesized, the same peptide was later shown to evoke the same behavioral actions as the natural brain peptide: mice treated with this peptide avoided dark areas. Ungar thus claimed to have isolated the first word in a chemical code for memory.

There is now a consensus on the interest of this original peptide, which is able to modify anxious behavior patterns in mice. The question arises, however, as to what the compound actually does. Is it, as suggested by Ungar, part of a chemical code for memory? Or is it simply a molecule able to modify emotions? This alternate hypothesis had already been proposed by Agranoff in 1970 at the meeting in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where Ungar presented his first data on scotophobin. Later work by Misslin et al. clearly demonstrated that scotophobin had a selective action on emotive mice, inducing marked avoidance of dark comers. The compound was therefore more likely to be an anxiolytic molecule rather than a chemical memory code word.

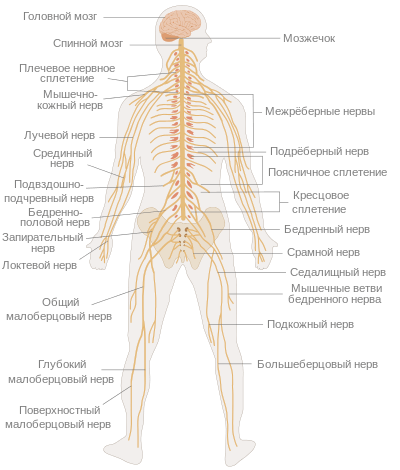

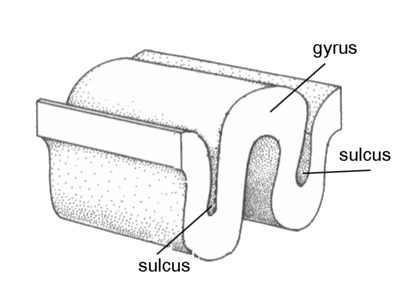

We can assume that, historically, the 1978 paper by Misslin et al. terminated, at least for the time being, the quest for a chemical code for memory. This conclusion does not mean that no molecule will ever be found to be involved in memory coding but rather suggests that if molecules do have a role to play in memory coding, then that role is likely to be more complex than that initially suggested by Hyden and Ungar. The idea of memory molecules acting without any direct link to the structural organization of the nerve pathways, or without structural interactions with networks such as the limbic system, seems unlikely. The structural organization of the nervous system and nerve pathways has led to modem approaches to the biochemistry of memory processes involving the action of brain neurotransmitters.

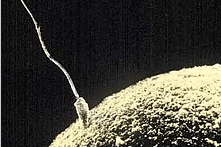

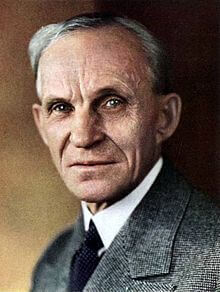

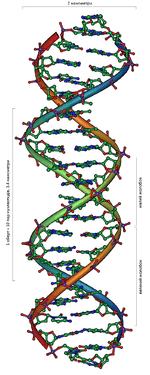

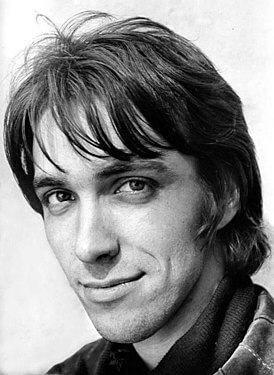

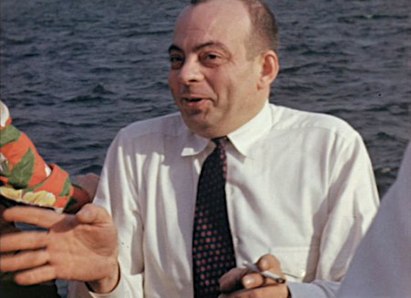

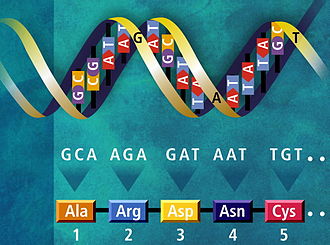

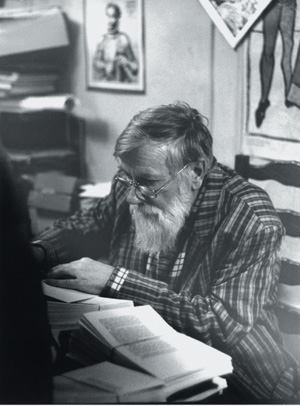

Larry Stern. The memory-transfer episode It’s March 1960, and James V. McConnell, an assistant professor of psychology at the University of Michigan, is convinced that planarians — common flatworms — hold the key to unraveling the mystery of memory. He has decided to condition them to scrunch when a bright light is flashed. Then, he plans to chop them into pieces, feed them to their cannibalistic brothers and see whether the learned behavior is transferred from the trained victim to the naïve recipient. His eventual goal is to demonstrate that the engram — the physical representation of memory — is encoded in the structure of unique forms of RNA much as inherited traits are encoded in one’s DNA.

The story of McCannibal and his Mau Mau hypothesis has become part of the folklore of psychology. Often used in textbooks as a humorous hook to grab students’ attention in chapters devoted to learning and memory, two things are typically included: references to memory pills or professor burgers and the alleged fact that no one was ever able to truly replicate the findings. Those who did report positive results, the story goes, were poor scientists who either conducted sloppy experiments that lacked proper controls or simply deceived themselves.

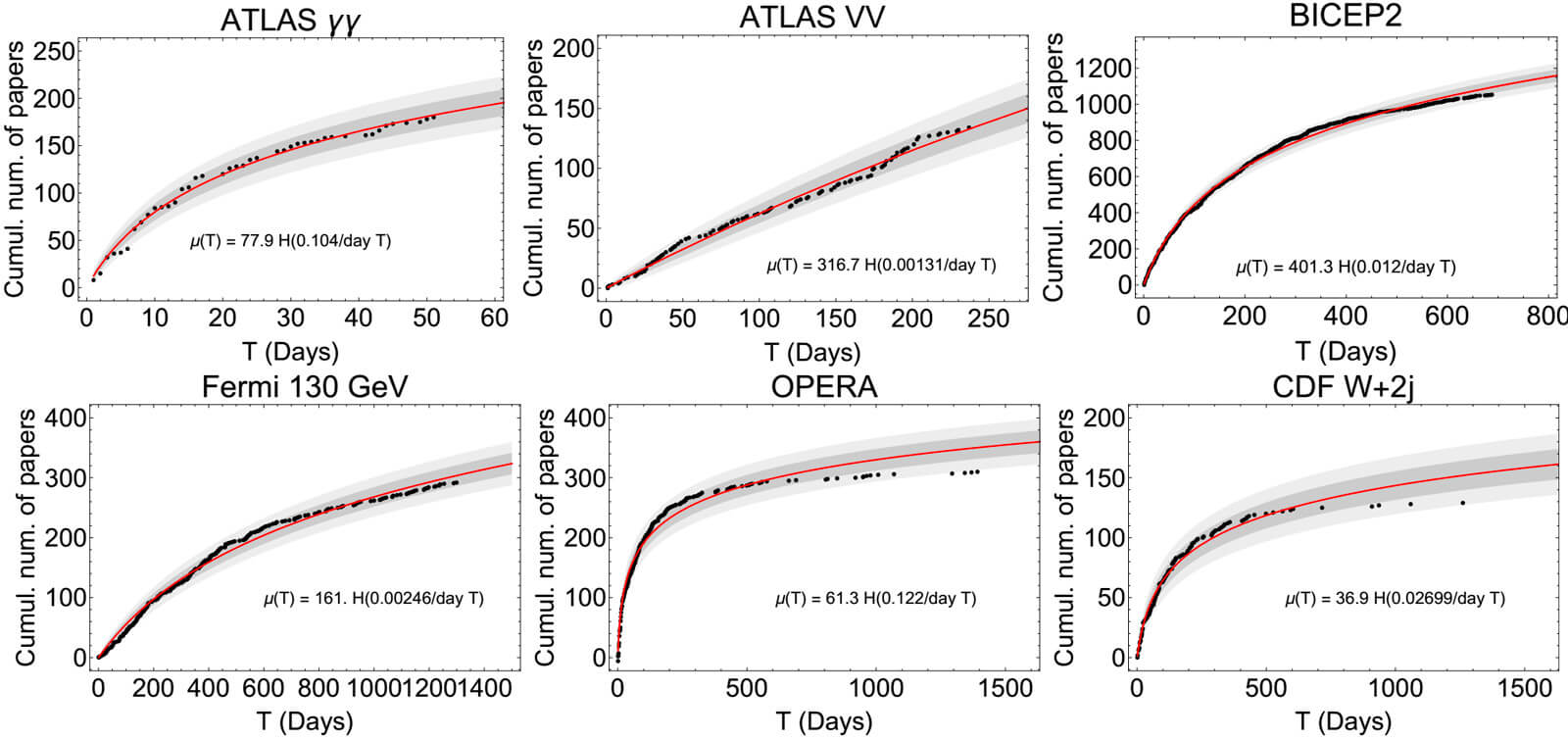

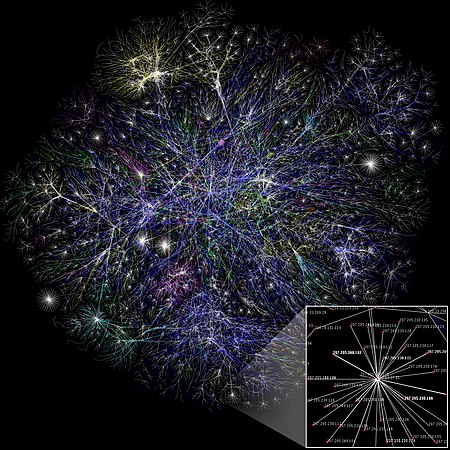

But folklore tends to caricature people and events and is lousy history. Although, in the long run, the work did not stand up to the exacting scrutiny of those working in the area of memory research, McConnell’s planarian studies spawned a 15-year episode that tells us much about the workings of science when it is confronted — as it always is — with claims that depart in significant ways from prevailing views. Equivocal results are typical in such episodes and to jump to the conclusion that those who championed a losing cause must be poor scientists is hazardous at best. In fact, by the time the dust had settled roughly 200 independent research teams — many in the upper tiers of science — conducted memory transfer experiments, using dozens of learning paradigms and 23 types of subjects including, in addition to the flatworm and standard lab rat, octopuses, praying mantes, baby chicks, kittens and honey bees. Government agencies granted more than $1 million to conduct such experiments, and 247 research reports appeared in print. Clearly, something was going on here; there were enough encouraging results to beckon others to try their hand. The early bird It started innocently enough. In 1953, McConnell, a graduate student at the University of Texas, collaborated with Robert Thompson to show that planarians could be classically conditioned.

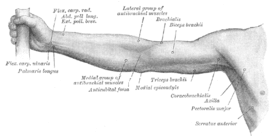

Thompson received his degree and went to Louisiana State University to work with rats, while McConnell, upon his arrival at Michigan, stuck with worms. He knew that by cutting a planarian across the middle into head and tail sections, each part would regenerate its missing half. But, he wondered, if you conditioned a planarian, which half of the bisected beast would retain the conditioned response? Working with two students in the newly formed Planarian Research Group, McConnell found, to his astonishment and delight, that the regenerated tails showed as much retention — and in some cases more — than the regenerated heads.

After nearly a year of McConnell’s wrangling with referees, the paper appeared in the Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. In his next experiments, McConnell and the PRG showed that each regenerated part of trained worms cut in several pieces retained the initial training and, more important, a planarian that, after several regenerations, contained none of the structure of the originally trained animal also retained the memory.

These results led McConnell to think more seriously about the chemical nature of memory. To test this notion, he needed to find a way to transfer the putative molecules from a trained to an untrained animal. But how? They tried to graft the head of a trained worm onto the tail of a naïve worm — but the head kept falling off.

Next, they tried grinding up trained worms and injecting them into naïve recipients, but that didn’t work, either. The hypodermic needles were too big — getting one inside a flatworm was like trying to impale a prune with a javelin — and if, by chance, the needle was positioned well enough to inject the planarian-puree, it either oozed out or caused the worm to explode.

The answer came in March 1960 when fellow worm runner Jay Boyd Best wrote McConnell about the cannibalistic tendencies of a particular planarian species. McConnell and the PRG ran pilot studies in April and obtained positive results. Each of the next four replications — each run blind to guard against experimenter bias — also produced promising results. Catching the public eye For many, these results were hard to swallow. That McConnell first reported these results in the Worm Runners Digest, a journal/magazine he edited that published a mixture of straight science and spoof, did not help his case. Of more importance, the planarian work was not easily replicable. The beasts were difficult to train, and various experimenters — most notably a team working under the patronage of Nobel laureate Mac Calvin at Berkeley — reported their failure to do so.

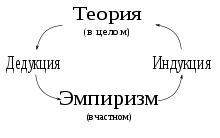

Theoretical concerns made the work even less palatable. The conventional view held that memory consisted of electrical impulses traveling along specific neural pathways. But the spectacular success of Watson and Crick led some to wonder: If genetic information is stored in nucleic acids and proteins, why not acquired information, as well? Although many neurophysiologists thought this analogy nothing more than a bad pun, a number of molecular biologists, thinking the time ripe to apply their tools and analytic approach to the study of memory processes, began to discuss seriously whether RNA played a pivotal role in memory processes. Expectations ran high, and work proceeded along a number of collateral paths. The smart bet, however, was that if RNA or any other biochemical agents played any role, it was merely to fortify and grease the wheels of neural processing.

McConnell wagered on the long shot. Soon after the cannibalism experiments, he successfully injected naïve worms with RNA taken from those trained to negotiate a maze and reported that the training had transferred. He interpreted these findings as providing evidence that specific memories are encoded in the nervous system in the form of unique structural variants of RNA.

The cannibalism studies, both startling and vivid in their imagery, and McConnell, never one to shy away from the media, caught the public eye. At a time when scientists remained sequestered in their labs, McConnell appeared with his cannibalistic worms on television, while articles profiling his work appeared in Time, Newsweek, Life, Esquire and Fortune. Eminently quotable, McConnell referred to his work as confirming the Mau Mau hypothesis, and the “McCannibal” moniker didn’t bother him one bit. He made grand pronouncements about the future of “memory pills” and “memory injections,” promising more than he and others working in the area could actually deliver.

None of this endeared McConnell to his critics.

Still, McConnell believed that eventually the data would win out, and many eminent psychologists, Donald Hebb, Harry Harlow, Karl Pribram, and Gordon Bower among them, fully supported his efforts, even though they did not share his interpretation of his results. In fact, up until 1965, McConnell was, as he put it, riding high. He was invited to share a platform with top-flight molecular biologists and electrophysiologists at conferences at the University of California, Los Angeles, in 1962 and Princeton in 1963. During the period from 1959 through 1964, he received more than $150,000 from the Atomic Energy Commission and the National Institute of Mental Health designated specifically for the planarian work. He was offered a fellowship to spend a year at the newly created Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences in Palo Alto, Calif., in 1960, and he received a prestigious five-year Research Career Development Award from the National Institutes of Health, 1963–68. He received accelerated promotion to full professor at Michigan in 1963.

Everything changed when, in late 1965, four independent labs reported successful memory-transfer experiments using rats. Two of these reports appeared in the high-impact journals Science and Nature.

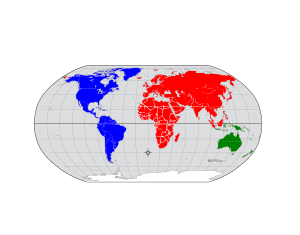

No one could argue that rats cannot learn. Within a few months, more than 50 labs, including teams at Berkeley, Harvard, MIT and Yale, conducted transfer experiments. McConnell, after failed attempts using salamanders and mynah birds, also turned to rats.

And then things got really interesting. |