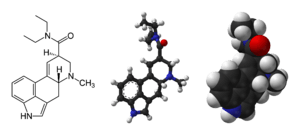

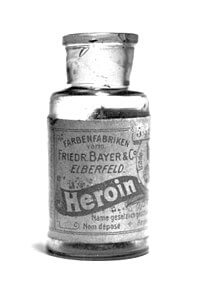

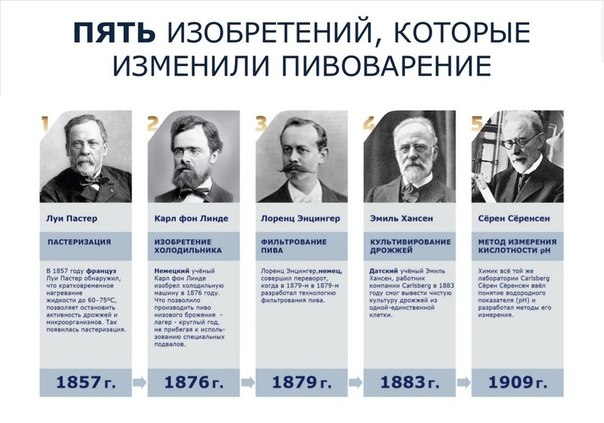

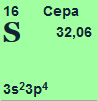

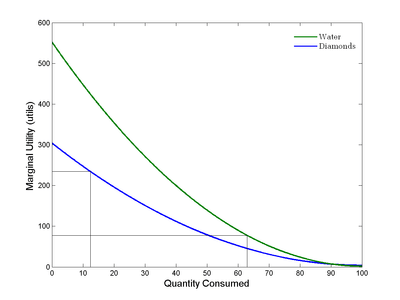

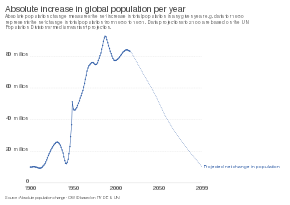

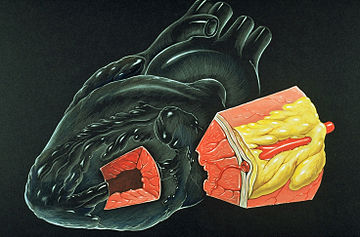

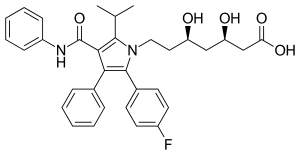

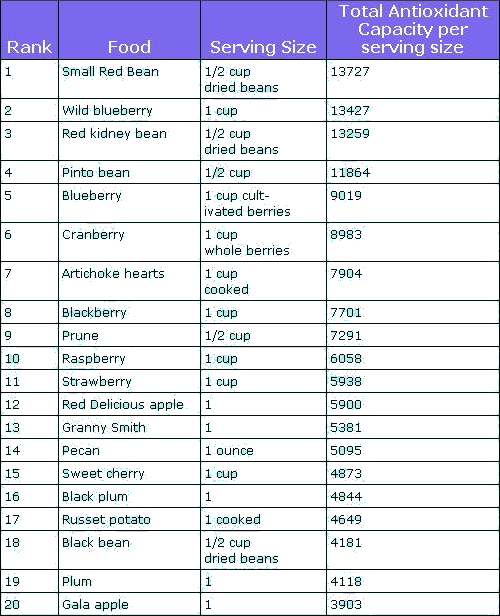

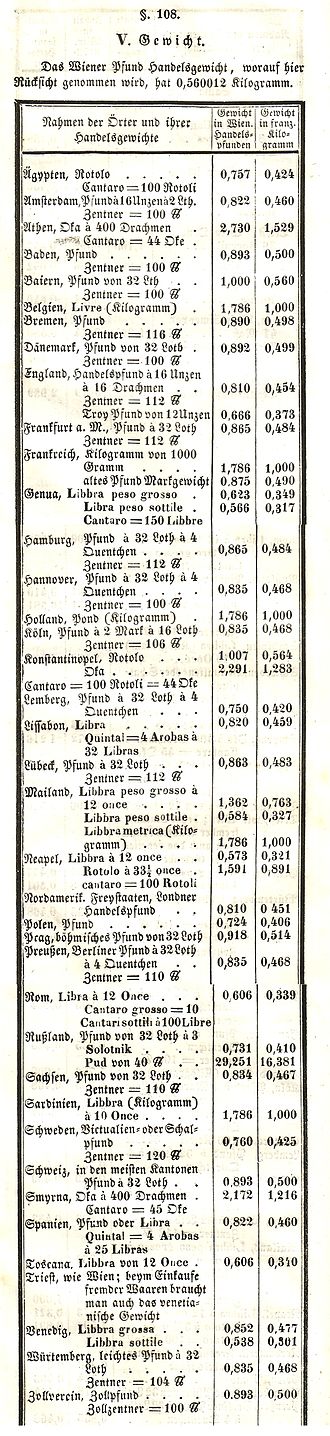

Social setting — applied aspectsAnd the potential applied aspects of these ideas raised the stakes considerably. If drugs could be found that would either enhance learning or if specific information could be introduced into an organism chemically, new therapies dealing with the treatment of senility, dementia, learning disabilities, and various forms of mental retardation could be developed. By the early 1960s two pharmaceutical companies were testing patentable memory drugs: Abbott Laboratories,

Abbott Laboratories is an American multinational medical devices and health care company with headquarters in Abbott Park, Illinois, United States.

of Chicago

City of Chicago, on Lake Michigan in Illinois, is one of the largest cities in the United States.

was conducting tests of the efficacy of a drug it named cylert,

Pemoline is a stimulant drug of the 4-oxazolidinone class.

while International Chemical and Nuclear Corporation of Los Angeles

Los Angeles is the second-most populous city in the United States, after New York City, and the most populous city in the Western United States.

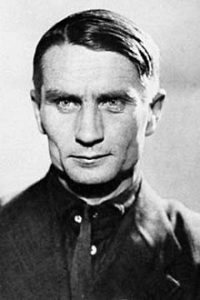

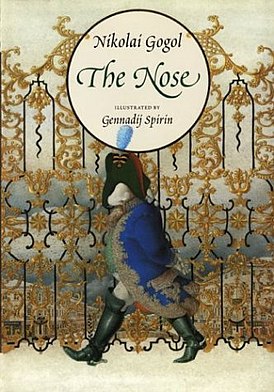

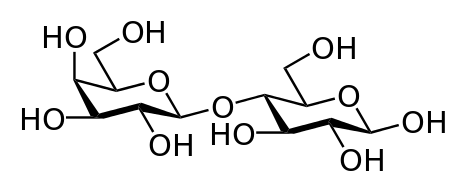

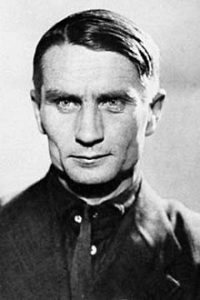

was testing ribanimol, a drug derived from yeast cells. So, let’s see; what we have here are ✓ cannibalistic worms; ✓ a theory, smacking of Lamarckianism, advocated by Lysenko

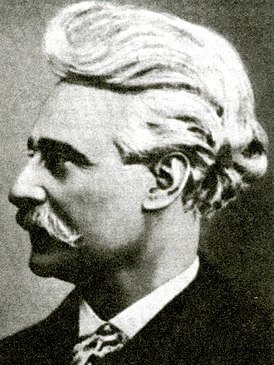

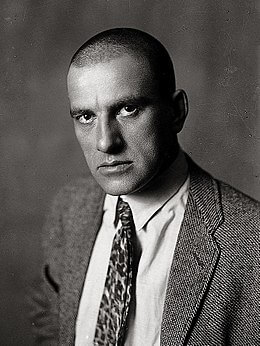

Trofim Denisovich Lysenko was a Soviet agronomist and biologist.

and adopted by Stalin;

Joseph Stalin was a Soviet revolutionary and politician of Georgian ethnicity.

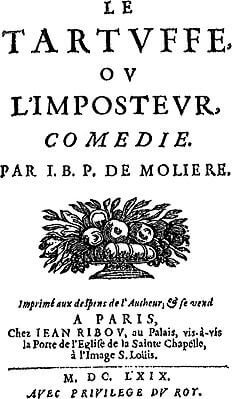

✓ a potential scientific breakthrough; ✓ conflict and controversy in the scientific community; ✓ enormous potential health applications; ✓ journalistic tendencies toward hype, hyperbole, and sensationalism; ✓ ethical issues such as mind control and Brave New World.

Brave New World is a dystopian novel written in 1931 by English author Aldous Huxley, and published in 1932.

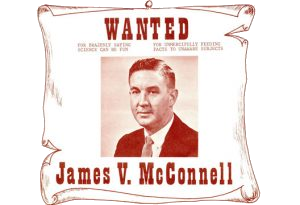

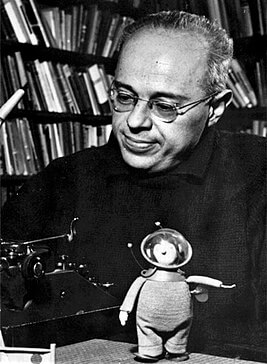

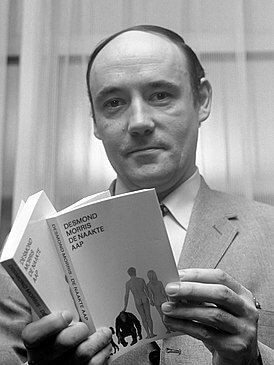

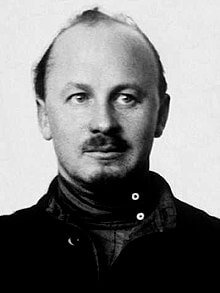

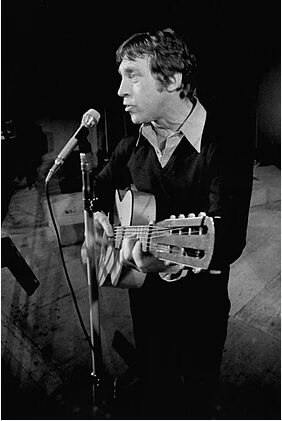

and James McConnell, a scientist with a media background, a sense of humor, and one who prides himself on telling it like it is All the ingredients – and more – of a journalist’s dream. Or the perfect storm, as the case may be. And throughout the episode, journalists, free-lance writers, and television producers constantly sought McConnell out. And McConnell didn’t disappoint.

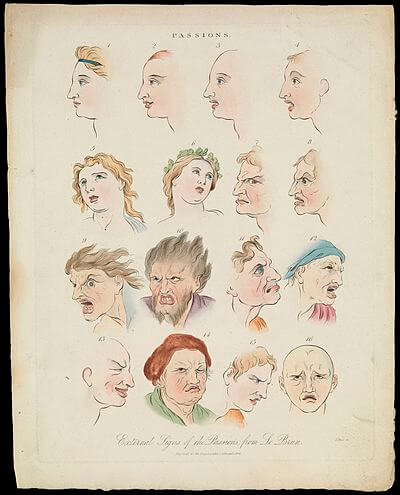

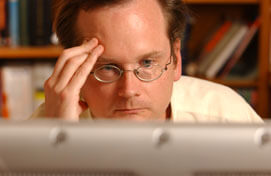

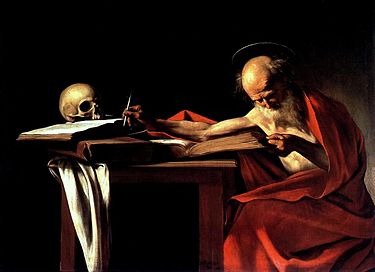

McConnell and mass mediaAt the time, surveys indicated that four general stereotypes of scientists were held by the public: (1) the eccentric, unfathomable, pre-occupied genius – a la Einstein;

Albert Einstein was a German-born theoretical physicist who developed the theory of relativity, one of the two pillars of modern physics.

(2) the dedicated, dispassionate, detached, objective, and humble researcher relentless in the pursuit of knowledge – 12 hours a day, seven days a week, often in isolation,

(3) the mad scientist of science fiction lore, and

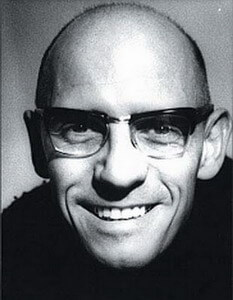

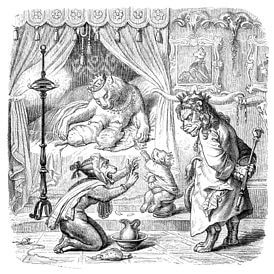

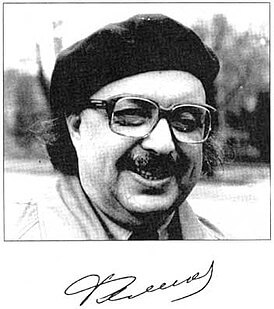

(4) the bookwormish, timid, bespectacled, shy, modest nerd. Although the bespectacled McConnell perhaps looked the part, one had only to meet McConnell to see that he was no nerd — he was, as I said before, some piece of work. He used calculated public relations techniques, calibrated to differing audiences, and was quick-witted, able to improvise at a moment’s notice. A small sampling: When, for example, McConnell was asked about his Lamarckian interpretation of his findings, he said Our work with flatworms does not entail sexual inheritance because the worms usually reproduced asexually. Lysenko’s projects have typically involved sexual reproduction, so actually there is quite a difference… But, our worms are now mating, and if we can get sexual inheritance we’ll crack the field wide open.

And then, with deadpan audacity We begin a series of experiments to test whether transfer could be accomplished through sexual reproduction. We get these big worms – really big worms – from Buckhorn Springs. We leave them alone to get acclimated – they mate – constantly. We start training them – they stop mating. We stop the training, they begin mating again… It makes you wonder about the value of an education.

The jokes about professor burgers started after coverage of a talk McConnell gave at an international symposium on drugs and human behavior, sponsored by Department of Psychiatry at the Presbyterian Medical Center

California Pacific Medical Center is a general medical/surgical and teaching hospital in San Francisco, California.

in San Francisco

San Francisco is a cultural, commercial, and financial center in the U.S. state of California.

It made the first of the San Francisco Sunday Chronicle.

San Francisco Chronicle Magazine is a Sunday magazine published on the first Sunday of every month as an insert in the San Francisco Chronicle.

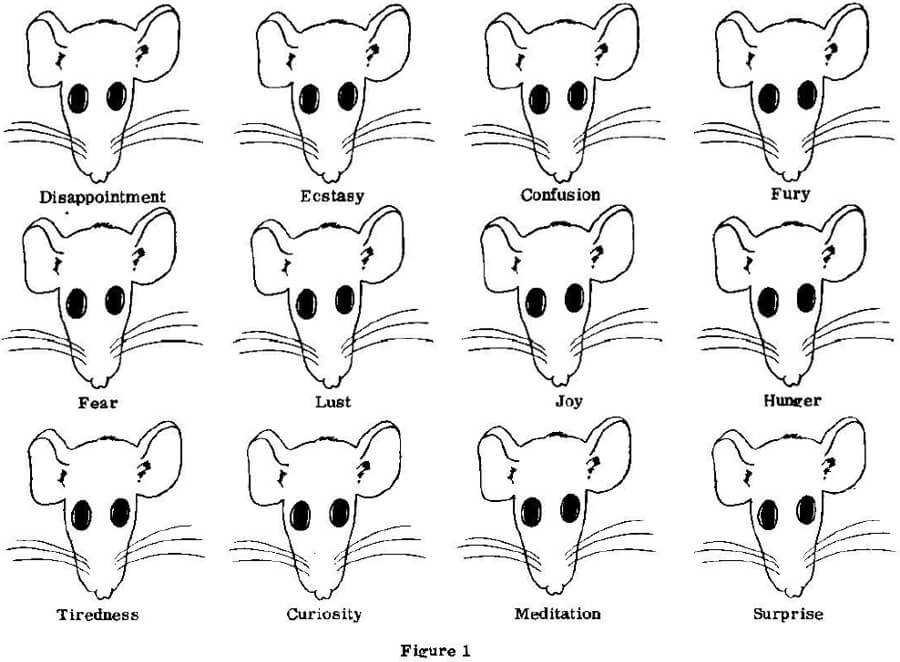

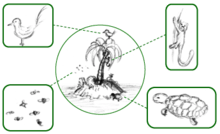

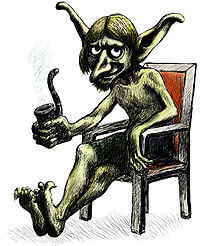

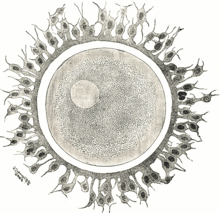

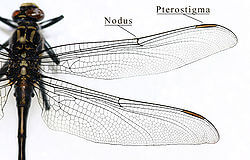

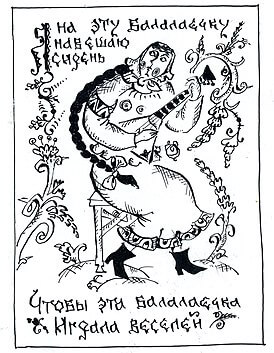

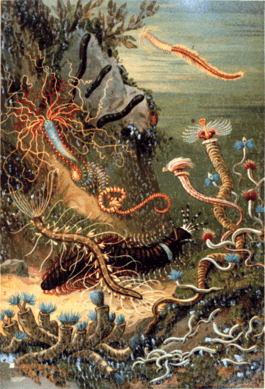

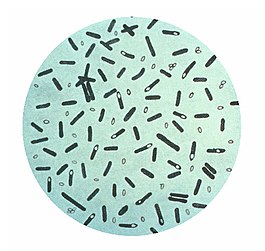

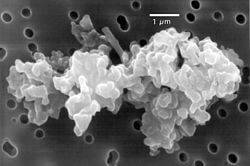

In addition to that statement, the artist’s drawing of the planarian that appeared in the early editions caused some concern. The pharynx — as you see — is somewhat out of proportion and seems to be protruding a bit. Changes are made in the second early edition — not to the drawing, but to the headline, which is now also branded a Scientific Shocker. Finally, by the late edition, the desk editor, realizing that such a drawing had no place on the front page of a family newspaper, found a proper scientific picture to replace the obscene drawing that appeared in the early-bird editions. Which prompted McConnell to say, To the best of my knowledge, it is the first time in history that the early worm has gotten the bird.

and then there’s the Worm Runner’s Digest. After Newsweek

Newsweek is an American weekly magazine founded in 1933.

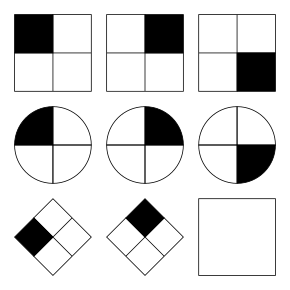

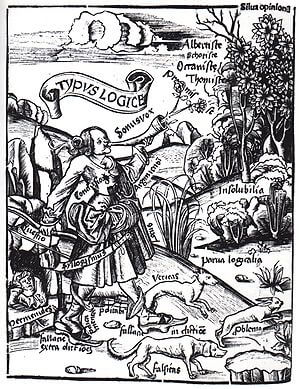

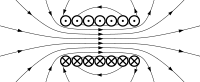

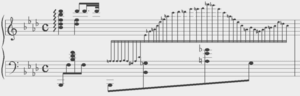

ran a story on his regeneration study in September 1959, McConnell, inundated with letters from hundreds of high school students from all over the country under some pressure to conduct a scientific experiment for their local science fairs, put together a fourteen- page manual describing how to care for and train worms. As a joke, he affixed the name Worm Runner’s Digest to the top. McConnell and the newly formed Planarian Research Group designed a crest complete with a two-headed worm, a coronet made up of a Hebbian cell assembly, the symbol for psychology, homage to the stimulus-response of behaviorism, and a motto, loosely translated as When I get through explaining this to you, you will know even less than before I started. The term digest, it should be noted, was decided upon before the cannibalism experiments – no pun here – and it wasn’t until years later, McConnell reported, that he learned that in the language of heraldry, diagonal stripes across your escutcheon means that you’re descended from a bastard. In any event, word of this new journal got out and McConnell, hoist by his own petard, as he put it, started receiving submissions. So he decided to pep things up a bit and poems, jokes, satires, cartoons, spoofs and short stories were scattered more or less randomly among the more serious articles. Articles such as The Effects of Physical Torture on the Learning and Retention of Nonsense Syllables, The Gesundheits Test, and The Effect of a Pre-frontal Lobotomy on the Mounting Behavior of the Congolese Red-Eyed, Thyroidectomized Tsetse Fly graced its pages, as did an article by McConnell in which he distinguishes between the unwitting, half-witted and whole-witted scientist. The first, lacking a funny bone and developing paranoid feelings of inadequacy, spends long hours in the lab, published a great deal and wins prizes. The half-witted scientist, though he can recognize – even pass on – a funny story, firmly believes that humor has no place in science. The whole-witted scientist, according to McConnell has an over-developed funny bone, known to choke him to death professionally, but he is often bolder and more imaginative than those scientists who are terrified of being wrong and hence seldom are right. The Digest, at its peak, had a circulation of around 1,200. But it was more than a scientific joke-book. It became a clearinghouse and safe haven for transfer studies rejected by mainstream journals – though I need to quickly make clear that only 62 of the 247 papers reporting transfer experiments – 25% – appeared in the Digest or in its spin-off twin, The Journal of Biological Psychology.

Biological Psychology is a peer-reviewed academic journal covering biological psychology published by Elsevier.

Perhaps most important, the journal provided McConnell a platform that he used to tell it like it is. Each issue contained a signed editorial/commentary that served to rally the troops. He informed readers and fellow travelers about works in progress, lab visits, and both front and back stage discussions at professional meetings. He responded to critics. He offered his running assessment of the controversy as he saw it unfold, commenting that some of his peers were a pretty narrow-minded and pig-headed lot. He cast himself as a heretic and as a David

David is described in the Hebrew Bible as the second king of the United Kingdom of Israel and Judah.

fighting the Goliath

Goliath is described in the biblical Book of Samuel as a tall Philistine warrior who was defeated by young David in single combat.

of establishment Science. None of this, as you might guess, endeared McConnell to many of his colleagues and critics.

McConnell’s Conference PresentationsMcConnell’s performances at disciplinary conferences – and they were referred to by many as performances – were a bit more restrained – but not by much. Research results were intermingled with self-deprecating humor, tweaking critics, taking listeners backstage, and offering admittedly speculative and wild sounding ideas. At a symposium on chemical correlates of learning at the mid-western psychological association McConnell referred to his ideas as wild, foolish and bizarre. He mentioned that one world famous naturalist, upon hearing of his regeneration study, shook her head and muttered, If you did what you say you did, and got the results you said you did, I suppose it’s true. But I still don’t believe it.

A moment later, listing replications of the study, McConnell included the work of a 13 year old 8th grader from Penfield,

Penfield is a town in Monroe County, New York, United States.

New York

New York is a state in the northeastern United States.

– he even showed her picture – and then commented that Somehow it delights me that results a world famous naturalist held to be impossible could be replicated by a bright 13-year-old junior high school student.

Introducing his tape recorder theory at a conference McConnell refers to it as 99% wild speculation and probably quite wrong, and to himself as a rather confused quasi-psycho-biologist… speaking on a topic that practically everybody knows more about than I do.

He then describes what he called a rude, crude, sloppily performed pilot study that he dare not publish. With good reason. The test tube containing RNA painstakingly extracted from 500 trained worms was dropped and shattered on the floor. Rather than trash three months of effort, they scooped the goop off the floor, re-centrifuged it to get rid of some of the impurities, and proceeded with the injections into naïve worms. And it worked! Still, not the sort of thing typically included in the methods section of experimental reports. In a letter written years later, McConnell admits that reporting that we dropped the first RNA on the floor is like admitting that one has farted in church.

An examination of McConnell’s extensive media files – which I shall not attempt here – gives clear indications that his work caught the public eye and stirred it’s imagination. Articles in newspaper and such magazines as Saturday Evening Post,

The Saturday Evening Post is an American magazine, currently published six times a year.

Life, Reader’s Digest,

Reader’s Digest is an American general-interest family magazine, published ten times a year.

Esquire,

Esquire is an American men’s magazine.

and Fortune,

Fortune is an American multinational business magazine headquartered in New York City, United States.

turned up on a fairly regular basis… M.C. Escher

Maurits Cornelis Escher was a Dutch graphic artist who made mathematically-inspired woodcuts, lithographs, and mezzotints.

produced a now-famous graphic. Charly, the story of a learning disabled man whose intelligence is temporarily enhanced, wins a Hugo Award

Maurits Cornelis Escher was a Dutch graphic artist who made mathematically-inspired woodcuts, lithographs, and mezzotints.

in 1959 for author Daniel Keyes

Daniel Keyes was an American writer who wrote the novel Flowers for Algernon.

and an Oscar

Oscar are a set of 24 awards for artistic and technical merit in the American film industry, given annually by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, to recognize excellence in cinematic achievements as assessed by the Academy’s voting membership.

for Cliff Robertson

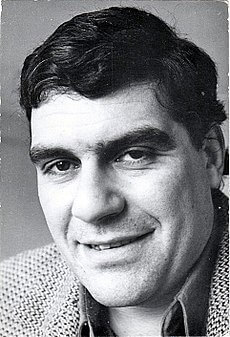

Clifford Parker Robertson III was an American actor with a film and television career that spanned half a century.

when the full feature film is released in 1968. Hauser

Dwight Arthur Hauser was an American film screenwriter, actor and film producer, also the father of actor Wings Hauser and actor Erich Hauser.

’s Memory, published in 1968 and made into a TV movie in 1970, tells the story a CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the United States federal government, tasked with gathering, processing, and analyzing national security information from around the world, primarily through the use of human intelligence.

supported experiment that injected the brain RNA of a dying German scientist who defected from the Russians into one of their operatives in order to obtain state secrets. And appearing daily in hundreds of newspapers in the U.S., those following the adventures of Alley Oop

Alley Oop is a syndicated comic strip created in 1932 by American cartoonist V. T. Hamlin, who wrote and drew the popular and influential strip through four decades for Newspaper Enterprise Association.

and his fellow cavemen – including, of course, Gus the King

King Gus is an American animated television series created by Paul Germain and Joe Ansolabehere and produced by Walt Disney Television Animation.

– in the Kingdom of Moo, read about the transfer experiments as they constituted the main story-line for a period of six weeks from October 6 — November 18, 1965.

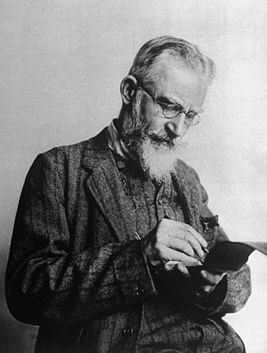

Personal costExamining this case, the sociologist David Travis has argued that McConnell’s style – his subversive flippancy and the aura of schoolboy humor that surrounded the work – adversely affected the reception of both McConnell’s work and that of others in the area. It’s important, Travis states, that researchers be seen as being earnest. Gail Corning, a discourse analyst whose husband worked in the transfer field, agrees. But, I’m not so sure. I have no doubt that a certain climate surrounded the work – one who worked in the area said the whole field had a stink to it. Were some put off by McConnell? Undoubtedly. Did some think the work noting more than a joke. You bet. Did some other proponents of the transfer phenomena try to distance themselves from McConnell? Sure. But it’s a lot more complicated than this. | Kathleen Stein. King of worm runners Barrelbottom now starts to type, first rather hesitantly… Occasionally he bounces off the chair: occasionally he stops to chew peanuts. Professor Skinnybox goes back to reading his Esquire.

The Digest was important in three respects, Travis says. It provided McConnell with an editorial forum: it carried bibliographies of al research relevant to the running of worms and the wider memory-transfer controversy: and it was often sent gratis to those who might be interested. But in the minds of many influential scientists, especially those in funding capacities, the already-outrageous transfer studies were further damned by their physical proximity to the Digest’s satire and laughter. The ambiguity of humor acted like an amplifier on McConnell’s already-controversial research. By the end of the Sixties he was severed from funding and was subjected to intense derision and prejudicial treatment at meetings and elsewhere. Let’s put it this way, McConnell explained as he wheeled around the Ann Arbor campus in his Mercedes with its BEHAVE license plate. «If my overriding goal was to get the transfer material accepted and win the Nobel Prize and become famous in that sort of way. I certainly would never have started the Digest. Obviously, subconsciously or whatever that wasn’t one of my goals. I went through an angry period in the Seventies. I had fought for four years to get grants. But I’m a person who believes in cutting my losses. In retrospect, the lack of funds forced me to go off and do other things. I never would have written UHB if Uncle Sam had continued to give me lots of cash. And the textbook has been verrry lucrative, and that means freedom. You can straighten a worm, but the crook is in him and only waiting. Mark Twain

Aside from indulging in satire and parody, McConnell broke other sacred taboos. He disclosed certain mechanical and human failures in the lab. He once admitted, for instance, that his air conditioner had gone on the blink and heated up some animals. Then there was the incident involving RNA: McConnell admitted publicly that some had fallen on the floor and he had scooped it up and stuffed it back into its container. Accidents will happen, but not to scientists. Reporting that we dropped the first RNA on the floor. McConnell commented, is like admitting that one has farted in church. At the time, though, McConnell had no idea he had so soundly violated the canons of respectability. Although I certainly did violate them. At the same time I thought many of my attackers were not all that intelligent, and that those who were bright were blinded by prejudice and emotionality. Now, however, I would probably view them as defending their egos. We did rather rip apart some deeply felt, almost religious beliefs about ‘the mind.’

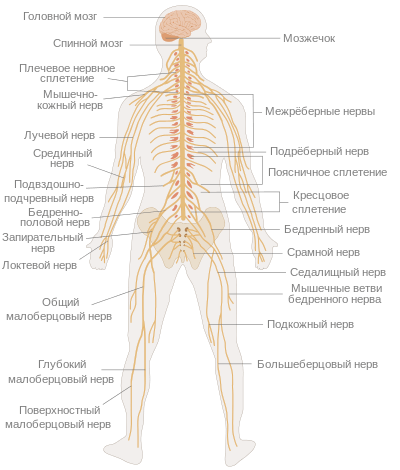

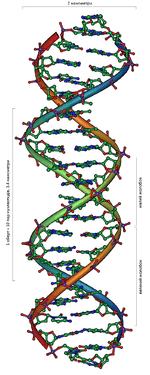

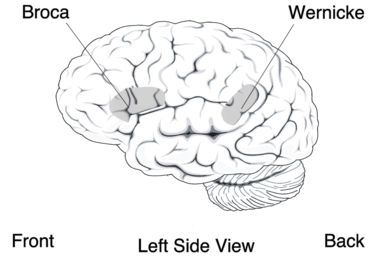

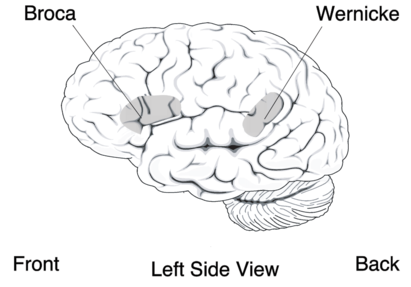

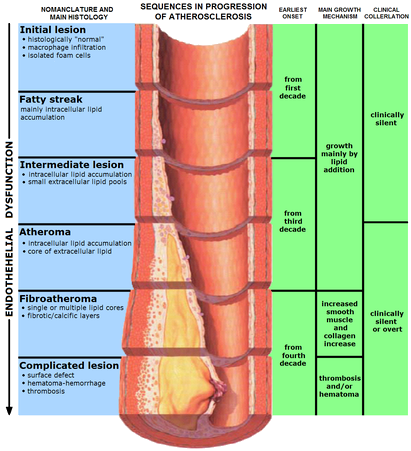

Most neurophysiologists in the Fifties and Sixties spent their lives studying the brain with electrical probes, thinking chemical events to be derivative: The memory-transfer research contradicted not one, but at least a dozen, of the acts of faith on which neuropsychology had been founded,

he said. We might as well have presented the pope with evidence that Mary was a whore, Jesus was a homosexual, and God was a black woman living in South Dakota. For we had really pulled the props out from under most scientists who thought they knew what the mind was. And the soul.

I suspect that if the response to our work had been more logical and less emotional, the Digest would never have been born and my own image as a humorist would have been confined to classroom iconoclasms.

Bernard Agranoff and Roger Sperry are only two of the eminent neuroscientists who told McConnell that if he were right, all of their life’s work was for naught. Sir John Eccles went further. As a devout Catholic, he worked out the mind/body/soul problem in a personal way. According to McConnell, Eccles believes in free will, yet he apparently had early difficulties resolving this concept with mechanistic physiology. So he put God at the synapse as a sort of Brownian movement of molecules. He once told me. McConnell remembered, he couldn’t believe in my work because it violated everything he knew about God. At the time I grew furious with him. I now wish I’d had better sense.

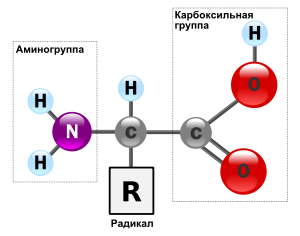

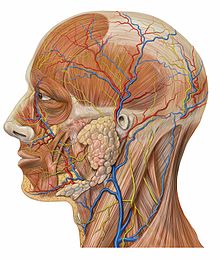

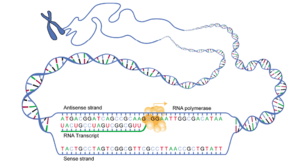

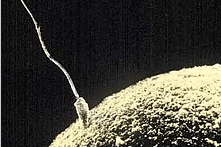

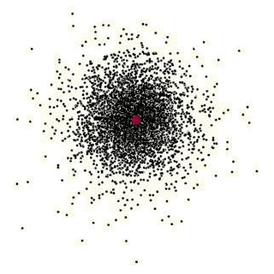

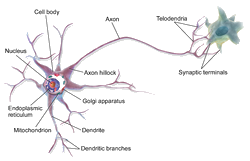

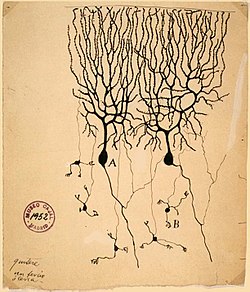

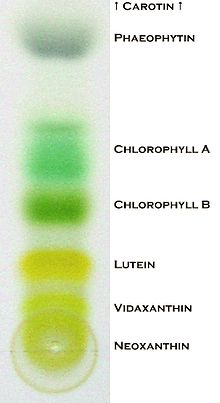

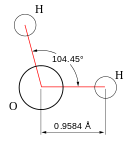

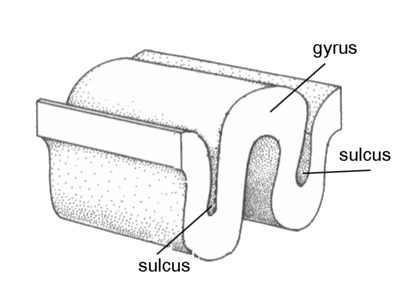

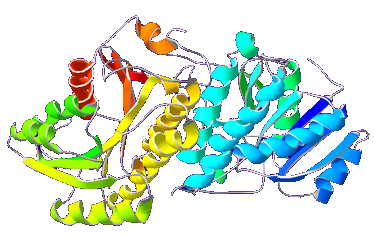

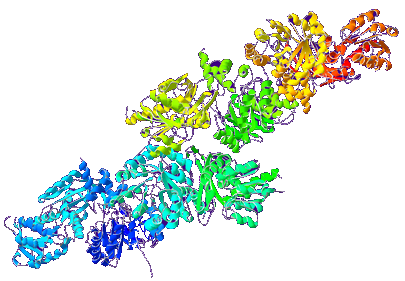

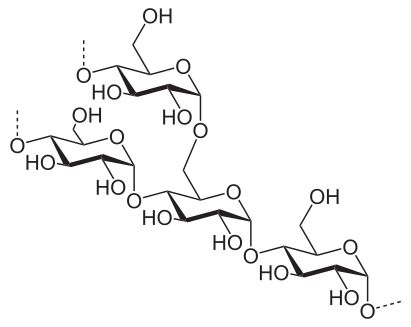

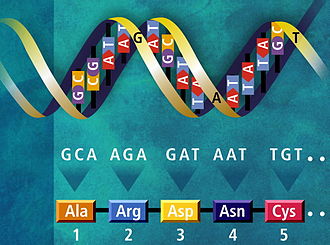

Today there is growing suspicion that thoughts and feelings may one day be traced to chemical events. Such thinking makes the transfer effect less dubious. Very little is known about what makes the brain tick. New neural connections are made, but no one has yet explained how. I think what we were doing was tapping into chemicals that are released from one neuron to another,

McConnell explained, putting into the system chemicals that caused neural growth to occur in a patterned way. This suggests that the proteins are actually ‘brief revisions’ of the neural blueprint you were born with. In the animal studies the injected RNA ‘told’ the neurons what new synaptic connections to make for learning to occur. When this blueprints were transferred from one animal to another, they gave the creature the molecular pattern it would otherwise have had to build up through experience.

But the field has gone by me,

McConnell admits, I wouldn’t know a molecule if it jumped up and bit me. What must be done next will be done by biochemists and neurophysiologists, and the next breakthroughs will reveal what the hell does happen chemically in the brain.

What do researchers in the biological basis of behavior say? Most restrict themselves to investigations at the neurotransmitter level. New York University professor of neurology and physiology David Quartermain admits that he is skeptical of the transfer theory, but he is willing to grant that there was some suggestion that something was transferred in those studies.

I don’t think they can be discounted as wrong,

he says, nor do I think McConnell and Ungar are charlatans. I think perhaps the something transferred might be a motivational factor, but given the structure of the mammalian nervous system – with all its exquisite detail – these complicated structural relationships suggest memory storage is more complex than we know now.

Nor does Quartermain, who is investigating protein-synthesis inhibition in the brain and looking for a way to ease memory disorders, discount the possibility that protein is a key element in memory. There’s got to be something to produce the change, if that change is durable. There have been some very elegant and informative experiments in which you train animals and see whether there are changes in the species of RNA or protein after training. Some of these experiments suggest that there is. I think this is area that will be understood within the next ten, twenty, or fifty years.

McConnell wryly points out that some RNA experiments have been done on humans – in organ-transplant recipients. It’s seldom talked about in literature, and I can’t give you any data on it, but it will be confirmed by any doctor working in the field. About fifty to sixty percent of the transplant patients show temporary psychotic symptoms after transplant. In kidney transplants it’s closer to ninety-five percent. No psychiatrist or psychologist measured them for possible memory shadows: I’m sure they’re picking up memories, or behavioral tendencies, from the donor.

Never fearful of speculation. McConnell thoughtfully entertains some farfetched ideas – such as learning pills. He will imagine a time when drugstores might carry bottles of protein compounds or RNA to enhance learning of calculus, say, or tax accounting, or anything else. Not everything, he cautions. What I would say is that we’ll be able to specify what family of chemicals is involved, for example, in learning Chinese. Then we’d synthesize them and give you daily injections, enabling you to learn Chinese five to ten times faster than normal. And to remember it better.

Science is, to a far greater extent than most scientists realize, the behavior of human beings who suffer the same personality quirks and fits of temper that everyone else experiences.

The years of worm running are behind him: the Digest terminated after 20 years for lack of funds. McConnell now turns his attention increasingly to teaching, writing, and the formulation of a unified-field theory of the brain, though he’s too modest to call it that. This quest includes a decade-long wrestling match with the redoubtable Skinner over the existence of the mind.

When McConnell was a trembling grad student, Skinner told him that the mind is a theoretical concept that we are better off abandoning. McConnell went away to mull that one over for 20 years.

Today he says, John Watson made the animal brain into an adding machine: Skinner turned it into a computer.

But Skinner still won’t look into the ‘box.’ With our knowledge of the hemispheres, we can now go much further into the head than Skinner is willing to go. At one lecture I pointed out to him that he can’t explain what he does when he trains a pigeon. He sets a goal for the bird, then directs its movements toward achieving that goal. In the interim he rewards the animal until it attains the goal. The trouble is, the goal is in Skinner’s mind. It does not exist anywhere else.

Skinner has never explained how an individual changes himself or modifies his own behavior. McConnell says, I say the left hemisphere is the pigeon and the right is the ‘Skinner’ that sets the goals, anticipates what the consequences of actions will be, selectively reinforces behaviors that are ‘emitted’ – Skinner’s word – by the left hemisphere. Skinner doesn’t like that at all.

|