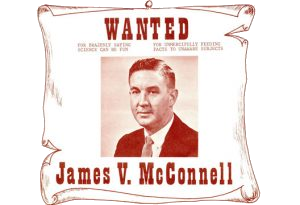

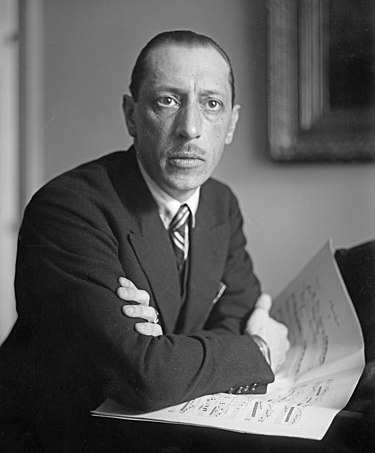

Personal Cost — Early YearsDespite the fact that there were critics at every turn McConnell was, in fact, riding high for at least the seven years following the publication of the first regeneration study. He was not teetering on a tightrope without a safety net. Quite the contrary. First, many prominent researchers voiced their support. Hebb was fully supportive, thanking McConnell for advance notice of the regeneration study and referring to it as work of the greatest importance: Thanks particularly for letting me know about your flatworm work. Very nice indeed. Congratulations…

It seems that your results show either that synapses are not modified at learning or there are two separable components or modes of learning. But, what you have already looks of the greatest importance for the problem and the possibilities equally great. Nice work.Hebb to McConnell, March 25, 1958.

A dozen years later Hebb still considered McConnell’s work to be somewhat of a breakthrough – even if the interpretation of the results needed revision: The memory transfer approach was and is an important line of research and the results can reasonably be described as a breakthrough, though interpretation of the results is still being debated.

McConnell discovered something important even if we are not quite sure what it is or how it works.D.O. Hebb, Review of the Worm Runner’s Digest, Psychology Today, May 1970.

Harry Harlow, editor of JCPP, was no less supportive and offered kind words of encouragement: Whether or not you believe it this research is, or approaches, the epochal. And any comments by the editorial staff merely expressed their state of mental surgical shock… Let me assure you that I am interested in this research, other psychologists will be interested.Harlow to McConnell, May 9, 1958.

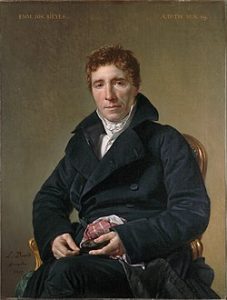

When McConnell asked Harlow if he could use some of his comments as supporting material in his grant proposals, Harlow readily agreed. When, in late 1964 criticisms of the planarian work began to mount Karl Pribram,

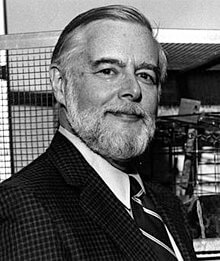

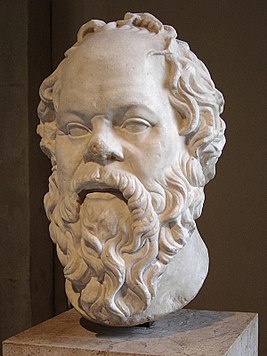

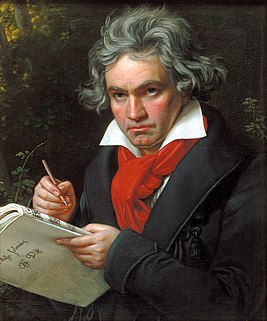

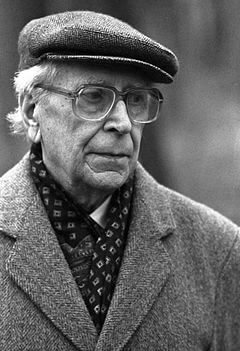

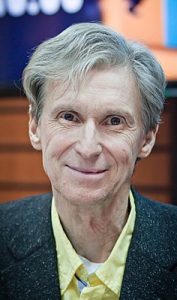

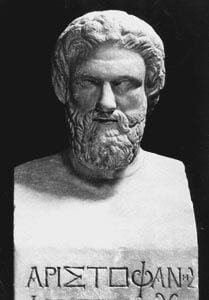

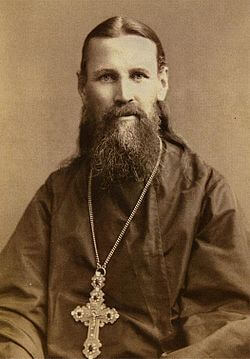

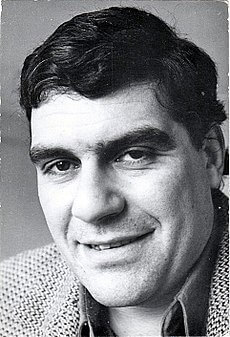

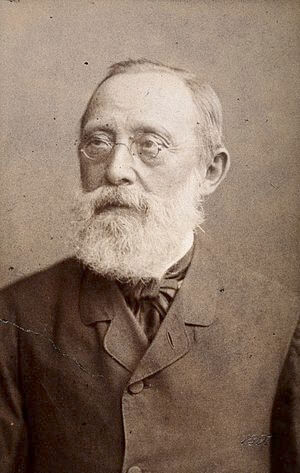

Karl H. Pribram was a professor at Georgetown University, in the United States, an emeritus professor of psychology and psychiatry at Stanford University and distinguished professor at Radford University.

wrote encouraging words, By all means, keep your chin up and plow ahead. The Bennett, Krech, and Rosenzweig people haven’t exactly had smooth sailing, either…

I tell you this only so that you realize that when anyone is in a new area one has to overcome conservatism and the very people who often are blazing the trail become most conservative when they wear another hat.Pribram to McConnell, January 18, 1965.

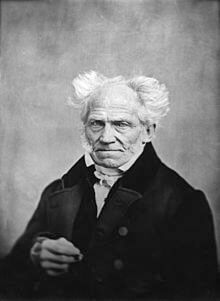

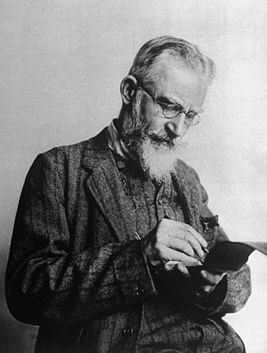

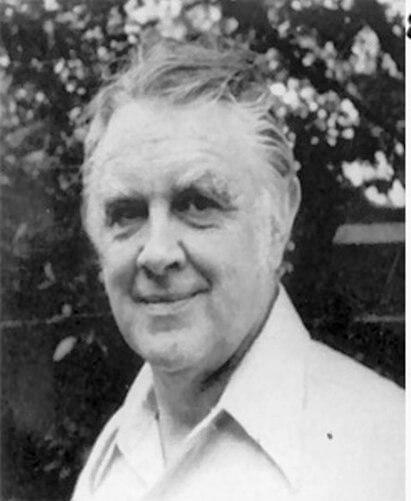

Karl Gordon Bower,

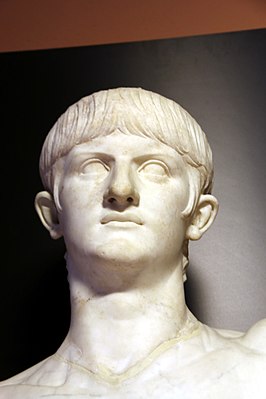

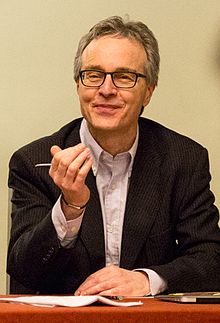

Gordon H. Bowerr is a cognitive psychologist studying human memory, language comprehension, emotion, and behavior modification. He received his Ph.D. in learning theory from Yale University in 1959.

too, voiced his support, writing that should a fight ensue, he was firmly in McConnell’s corner. I believe you and your work. At a time like this it is difficult for you not to be upset and almost obsessed with the dispute. I’ve been in one or two minor scientific disputes of my own and I know the mixed feelings of threat and indignation. I hope my expression of confidence and admiration for your work helps to reduce at least some of your despondency. If you choose to consider yourself in a fight then view me as lined up firmly in your corner. I hope this fray does not inhibit the productivity of your laboratories.Bower to McConnell, February 1, 1965.

At the same time, McConnell was offered a seat at the table – he was invited to share a platform with top-flight molecular biologists and electrophysiologists at important conferences. He joined such luminaries as Seymour Benzer,

Seymour Benzer was an American physicist, molecular biologist and behavioral geneticist. His career began during the molecular biology revolution of the 1950s, and he eventually rose to prominence in the fields of molecular and behavioral genetics.

Mack Calvin, ,

Mack Calvin is an American former basketball player.

D.A. Glaser,

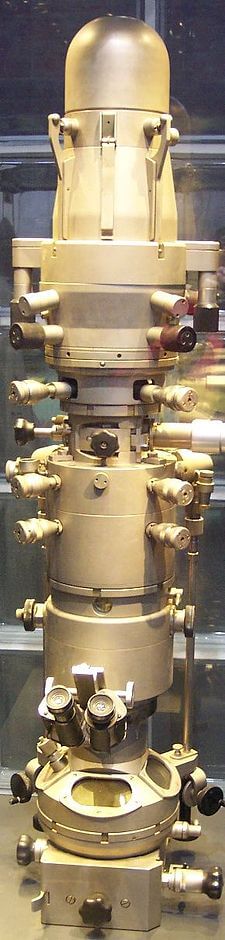

Donald Arthur Glaser was an American physicist, neurobiologist, and the winner of the 1960 Nobel Prize in Physics for his invention of the bubble chamber used in subatomic particle physics.

Marshall Nirenberg,

Marshall Warren Nirenberg was a Jewish American biochemist and geneticist.

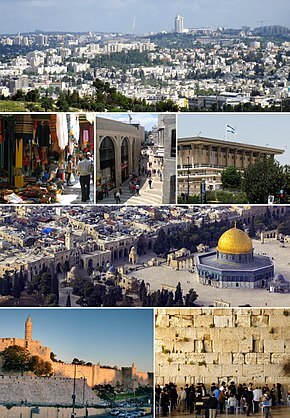

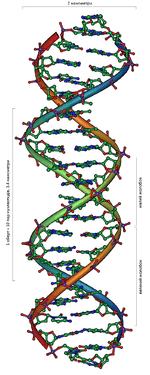

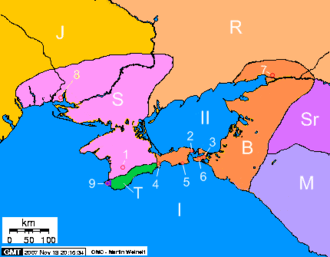

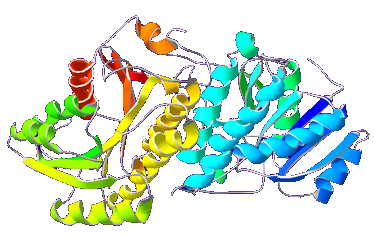

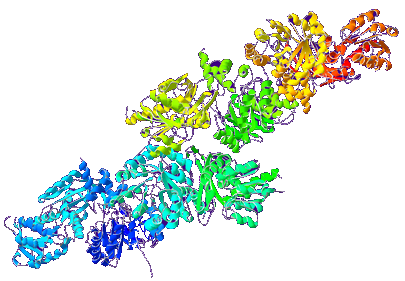

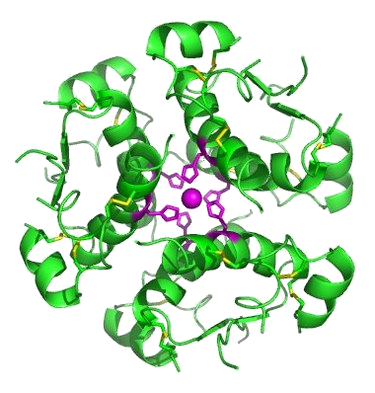

and Holger Hyden for a small, specialized conference on the role of RNA in memory processes at UCLA,

The University of California, Los Angeles, is a public research university in the Westwood district of Los Angeles, United States. was a Jewish American biochemist and geneticist.

in 1962. One year later, McConnell was invited to join such heavyweights as John Eccles,

Sir John Carew Eccles was an Australian neurophysiologist and philosopher who won the 1963 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on the synapse.

Roger Sperry, Neal Miller,

Neal Elgar Miller was an American experimental psychologist.

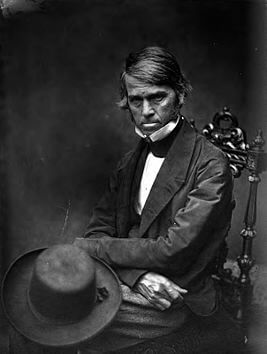

David Krech,

David Krech was a Polish-born American experimental and social psychologist who lectured predominately at the University of California, Berkeley.

Eugene Roberts,

Eugene Roberts was an American neuroscientist.

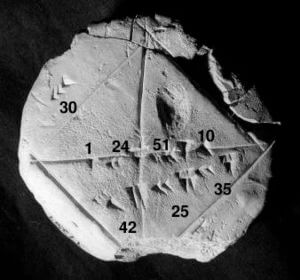

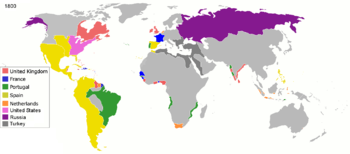

– the list goes on – at the First Conference on Learning, Remembering and Forgetting held at Princeton. No ostracism, here. Nor was McConnell hurting for money during this time. Considering only those decisions made up through 1965, we can see that the Atomic Energy Comission,

The United States Atomic Energy Commission, commonly known as the AEC, was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by U.S.

provided close to $114,000, while the National Institute of Mental Health,

The National Institute of Mental Health is one of 27 institutes and centers that make up the National Institutes of Health.

provided roughly $42,000 specifically for the planarian work in addition to a prestigious Career Development Award. In house funds from the University of Michigan amounted to $53,000. Nor was job security much of an issue. Hot on the heels of the cannibalism studies came an offer to become the Associate Director of the Britannica Center for Studies in Learning and Motivation in Palo Alto,

Palo Alto is a charter city located in the northwest corner of Santa Clara County, California, United States, in the San Francisco Bay Area.

at the handsome salary of 15K plus a percentage of the profits. By the way, that’s about 100K+ in today’s dollars – for a guy without tenure yet. McConnell spent a year there and, to get him back to Michigan he was promised – and received – accelerated promotions, coming back as Associate Professor with tenure in 1962 and promoted to Full Professor the following year. All told, this sounds like one heckuva safety net, don’t you think? And, quite frankly, it was good that he had it.

Personal Cost — Later YearsCircumstances changed dramatically in late 1965 when the first successful transfer experiments using rats were reported more or less simultaneously by four independent labs – none of which were McConnell’s. One of the difficulties with the planarian experiments was that many simply couldn’t believe that a worm was capable of learning, much less pass that on via cannibalism or injection. But nobody doubted that rats could learn. Although he had planned some experiments with rats, McConnell was now behind the curve. Dozens of labs tried their hand at eliciting the transfer phenomenon as the field heated up. Those that obtained promising results worked together in a spirit of cooperative competition, each trying to nail down the best learning paradigm – and then convincing the others to drop what they were doing to replicate their findings. McConnell – a primadonna – was no longer the top dog. He switched to rats – and, in fact developed what he thought was a darn good paradigm – but he couldn’t convince others to try it out. His grant money dwindled. NIMH refused to renew either his planarian grant or extend his career development award. Neither the National Science Foundation,

National Science Foundation is a United States government agency that supports fundamental research and education in all the non-medical fields of science and engineering.

NASA,

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration is an independent agency of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States responsible for the civilian space program, as well as aeronautics and aerospace research.

nor the Office of Naval Research,

The Office of Naval Research is an organization within the United States Department of the Navy that coordinates, executes, and promotes the science and technology programs of the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps through schools, universities, government laboratories, nonprofit organizations, and for-profit organizations.

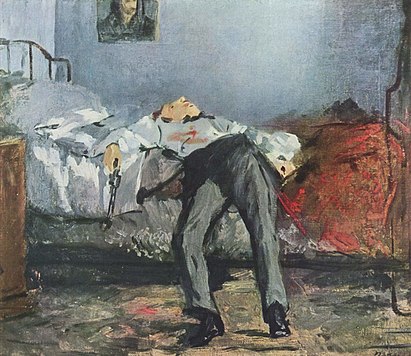

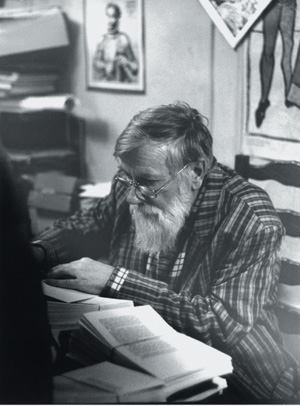

chose to fund the worm work. NIMH passed on a proposal using amphibians as experimental subjects. The University gradually withdrew its support as well. Most – but not all – of McConnell’s rat proposals were turned down as well. As can be seen, a few mini-grants were awarded and, finally, NIMH approved one in 1969. The earmarked funds, however, never materialized due to governmental budget cuts. All told, McConnell’s research funds after the field moved to rats was $33,000 – roughly 10% of the amount he had in previous years. McConnell has stated that he lost grants and that his credibility suffered because of the Worm Runner’s Digest and his tell it like it is style. Perhaps. But letters from grant agencies cite other reasons that, on the face of it, seem equally compelling. After all these years McConnell was still asking for funds to develop a simple, reliable technique for demonstrating the phenomenon. He was still proposing parametric studies. It didn’t appear as if he’d been making much progress, while others, like Georges Ungar, was in the process of isolating and determining the chemical structure of a putative memory molecule. McConnell with no biochemist on his team, had no intention of doing this. One might say that he field had outpaced his competences and passed him by. There is no question that McConnell felt wounded. By the early 1970s he felt slighted by other transfer workers, no longer being invited to serve on panels at meetings. And there is no doubt that many still working in the area were trying to put as much distance as they could between themselves and McConnell. But not because of his style. It was his theory that denied the importance of neural networks. It was troublesome in the beginning, and more so now that other approaches had begun to bear fruit. By 1971 McConnell closed down his lab, began writing what was to become a best selling textbook. Living well, he always said, was the best revenge. And he returned to one of his first loves – Skinnerian behavior modification – with the same subtlety that was his trademark. Which brought severe criticism from Angela Davis,

Angela Davis is an American political activist, academic, and author.

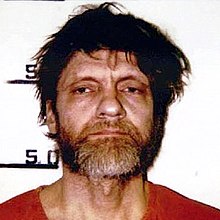

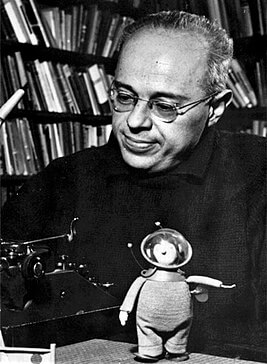

and, far worse, from Ted Kaczynski,

Ted Kaczynski also known as the Unabomber, is an American domestic terrorist.

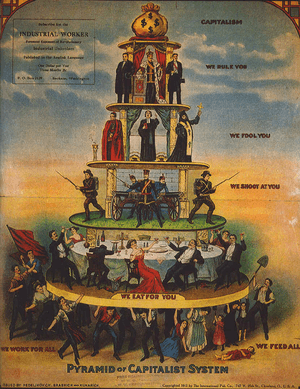

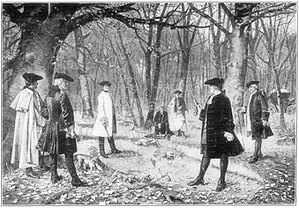

AKA, The Unibomber. Picture me, twenty years ago, wearing my stylish aviator sunglasses. Is it any wonder that McConnell set the feds on my trail – but that’s another story – perhaps after drinks at the banquet tonight. But what about the transfer field as a whole? Did it suffer because of McConnell’s supposed antics? I think not. There’s no doubt that McConnell did not do himself or his colleagues pursuing the transfer phenomenon any favors with what many perceived to be his unfortunate style of presentation. And it is certainly true that many researchers simply stopped reading the literature that continued to see the light of day as the episode proceeded. But despite all this, some stubborn facts remain: At least 170 independent researchers or research teams devoted differing amounts of their time, energy and resources conducting transfer experiments. These were reputable scientists – not fringe fanatics. On average, those scientists conducting MT received 3X as many citations to their work each year than their counterparts, and more in one year than most receive in 5. Nearly 20% of transfer workers received 30 or more citations the year they conducted their transfer experiments. Typically, only 2% of all scientists do so. More than $1 million in grants were awarded specifically for transfer experiments Two-hundred forty-seven experimental reports were published, 75% in journals other than the Worm Runner’s Digest/Journal of Biological Psychology. Although it is difficult to say precisely how many researchers and how much money is needed to investigate any given phenomenon, it seems to me that a critical mass had been achieved. And to say that scientists stayed away because of McConnell – and not because of cognitive assessments… well, maybe the more pedestrian ones. But let me conclude with one point that sorely needs to be further developed. As odd or strange or amusing as this case may appear to be, I would argue that the overall reception of this work was quite in keeping with the normal state of affairs in the scientific community. That is to say, nearly all philosophers of science – including the likes of Kuhn, Popper, Lakatos, Feyerabend, Agassi – folks who ordinarily can’t agree over whether it is raining or sunny outside – all agree that extraordinary scientific claims – claims that depart in significant ways from prevailing cognitive frameworks – must be accommodated in some way – at least for a time. There is no sure way of knowing when a claim is first introduced whether it will be a boon or a bust. Bold conjectures should be vigorously discussed and be granted a grace period, or these claims should be sheltered. And, as sociological fine-grained analysis of case studies have indicated, this is where much of the action is in science as outcomes are socially negotiated within the parameters set by cognitive constraints. But all this remains for another day. Let’s leave the last words to McConnell: It was the validity of the transfer effect. If anyone had gotten something, where you could constantly – where any stupid jerk could go into the laboratory and get a transfer effect, you wouldn’t be here and we wouldn’t be arguing. It was he shakiness of that, of the basic effect that caused the problem… I think if we could replicate it again and again and again all of the rest of the stuff would have been trivial. . . . I mean, you can hate somebody’s guts, but if their stuff replicates again and again and again you’ve got to live with it. You’ve got to adjust to it. Since that wasn’t the case these other things came in.

| Kathleen Stein. King of worm runners Next serve, Dr. Skinner.

McConnell thinks back over all the weird battles he’s somehow found himself in. I suppose my only regret is that I still can’t tie all of the memory-transfer data and hemisphere studies into one pretty package. But the thing I’m proudest of – even more than my so-called honesty – is the fact that I didn’t push the transfer effect more than I did. If I have one talent, it’s for propagandizing. Look at my textbook – it’s a six-hundred-page commercial for my version of the scientific method. I flatter myself that I could have created a ‘school,’ or at least a large set of disciples, had I chosen to play the guru’s role. But at some deep level a little voice tells me that if the facts don’t sell themselves, they may not be valid.

Yet McConnell is one of a certain endangered subspecies of scientists, poets, inventors who feel the faint, nagging suspicion that they are born too soon. By just a few years. His whole theory will fit together in neat, interlocking pieces anytime now. Of course, had I understood ten years ago what I do now, much of controversy would never have taken place. Having been stocked to the core by the Nobel laureates, I’m sure I defended my own ego by resorting to humor. Part of my wit was bitter attack. But part of it was little more than the same submission response that a young wolf shows to the pack leader when he bares his throat in self-defense. Better to be laughed at than crucified, if you know what I mean.

Would he do the whole thing over again? Yes, except I would have qualified all my earlier statements with theoretical garbage and a barrage of ‘ifs’ and ‘perhapses.’ I never would have used the term memory transfer. ‘Transfer of response bias’ is so delightfully neutral. I would have appeared dead serious and refused to smile at anything. And I would have gone mad.

Will James V. McConnell usher in the new order, construct the paradigm shift in psychology? Will this maverick be seen as a pioneer who helped initiate structural changes in the study of the brain?

Perhaps, like the coyote in North American mythology, McConnell is the trickster who, in his ambiguous role and mischievous duality, is a crucial mediator in problem solving. The temptation is to take a long run along the worm’s magic electrified field, to sweep out science’s Augean stables with a good belly laugh.   H. Brown, B. Corbett. On the solution of all philosophical problems through the consistent application of the Peter principle It has long been a primary goal of philosophers to put themselves out of business by solving all philosophical problems. Previous attempts to achieve these noble goal have failed through lack of a sufficiently powerful principle. Such a principle has now been supplied by the Peter Principle which, in its most general form, states: Everything tends to rise to its own level of incompetence. In this paper I will demonstrate how the Peter Principle can be used to solve all philosophical problems. The paper will be in two parts. In part I the method will be illustrated with respect to two classical philosophical problems. In part II a consideration of a third problem will provide the basis for a proof that the method is complete. I A) Why is there anything rather than nothing? Originally there was nothing. Since this was working out quite well, nothing was promoted to something which it has been doing incompetently ever since.

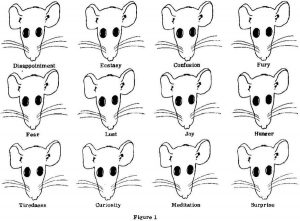

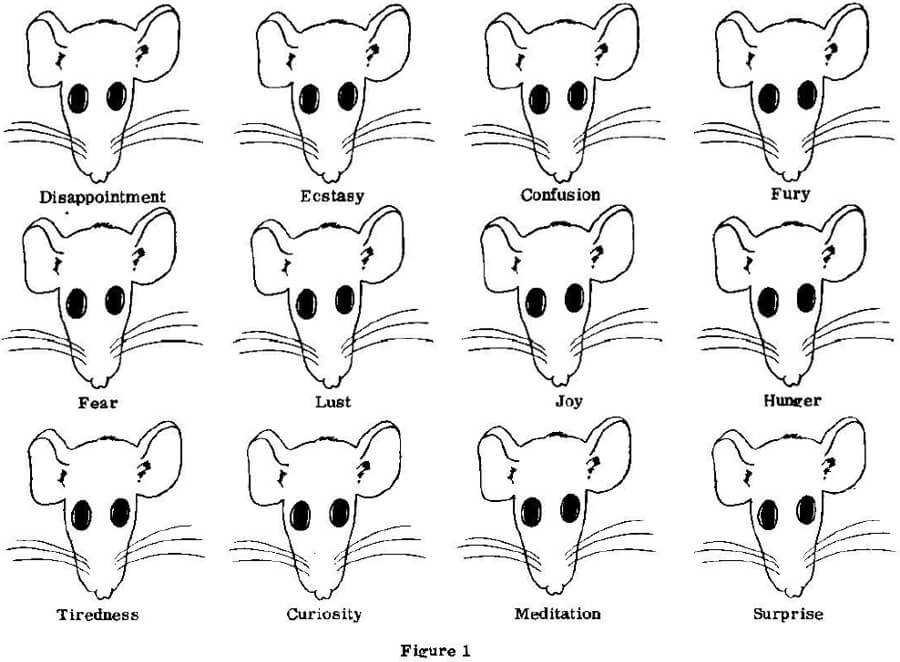

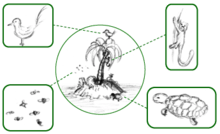

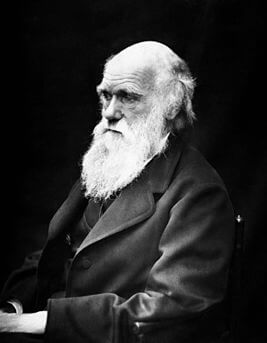

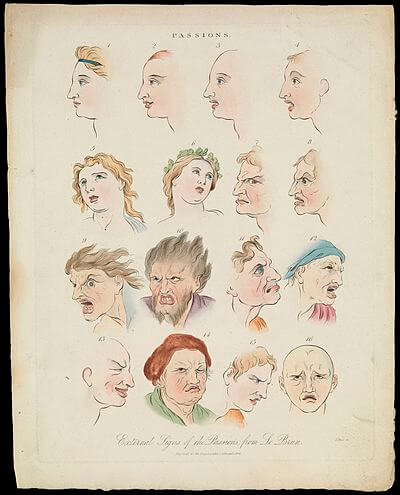

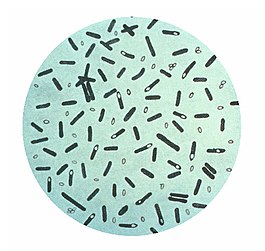

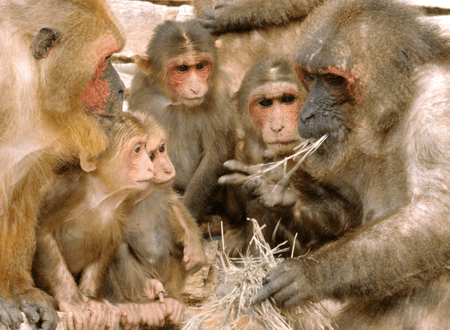

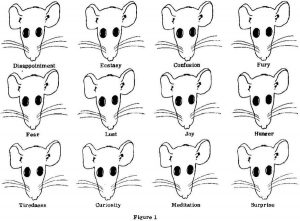

B) What is the nature of the relation between mind and body? Previously there was no relation between mind and body. They were not on speaking terms and had absolutely nothing to do with each other. Since this was thoroughly efficient arrangement, mind was promoted to the job of controlling the body, which it has been doing incompetently ever since. II Let us attempt to apply our method to the problem of freedom and determinism. We could argue that man was originally free and that since this worked well, freedom was promoted to determinism at which it is incompetent. But it is equally plausible to argue that man began in a state of competent determinism which was then promoted to incompetent freedom. Clearly, we have no way of choosing between these arguments. Thus the Peter Principle cannot solve this problem; in attempting to use the Peter Principle to solve all philosophical problems we have promoted it to its level of incompetence from which we infer that the method of complete. This inference is surely incompetent, which we take to be a further proof of our thesis.  Hank Davis and Susan Simmons. An analysis of facial expressions in the rat It has long been that facial expressions may be a sensitive indicator of an organism’s emotional state. Who can forget Darwin’s classic work, The Expression of the Emotions in Man and the Animals, in which he painstakingly catalogued the faces of primates to illustrate his point. This area of investigation has found favor with modern researchers as well. Mariott and Salzen have analyzed the facial expressions in a colony of captive squirrel monkeys and they, like Darwin, have concluded that a smile is worth a thousand words. All things considered, it is really surprising that no one has gone to the trouble to record and analyze the facial expressions of the ubiquitous rat. This surely must be an oversight and we intend to put things right. There has, of course, been related work with mice (Disney), thus indicating that the problem is not in soluable. A little effort is all that’s needed. If we’ve learned anything from the past decade of animal psychology, it’s that we must really know our subjects before we can work with them. And what better way to know anyone than to study his or her face? Method Subjects. Our subjects came from a colony of laboratory rats. We could only get used ones, so they came to us in a variety of moods; some happy, some sad, some scared to hell, depending upon the studies in which they’d participated.

Procedure. We watched our subjects for three months. Really watched them. Then we drew them.

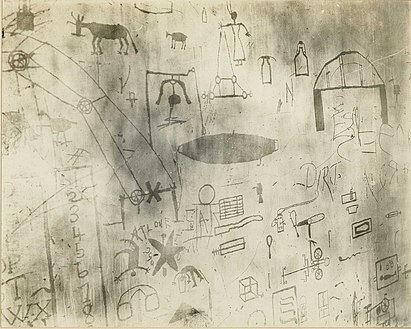

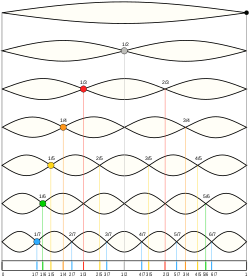

Results and Discussion Figure 1 illustrates the faces of rats produced by 12 separate and distinct mood states. It is notable that a high degree of similarity exists between the facial expressions associated with each of these moods. We’re not too sure why this happened. Without getting too graphic, we can assure you that the procedures we used to induce the different mood states were effective. Similarly, our artists and observers were no slouches.

One possibility is that our rats, born and reared in the lab, have been stultified for generations and have lost their facial-expressive abilities. It is therefore essential that our study be repeated under more natural conditions. The only remaining conclusion, and it’s a bit late to be worrying about this, is that rats may not be as facially expressive as we initially thought. Maybe this is why nobody else has messed around with this stuff before. Anyway, it may be about time to validate some of the widely circulating reports of Disney and the colleagues. ReferencesDarwin, C. The expression of the emotions in man and the animals. London: John Murray, 1872.

Disney W. Mickey Mouse and his pals. Burbank, Ca., 1929-present.

Mariott B. & Salzen E. Facial expressions in captive squirrel monkeys. Folia Primatologica, 1978, 28, 1 – 18.

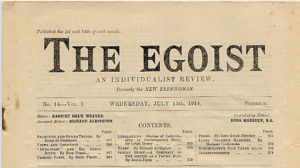

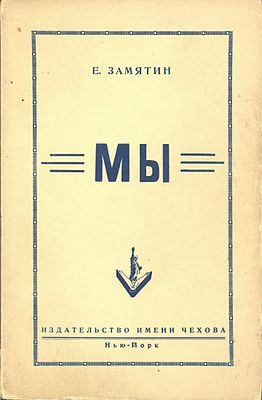

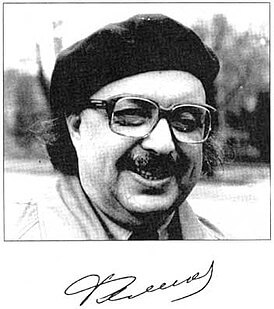

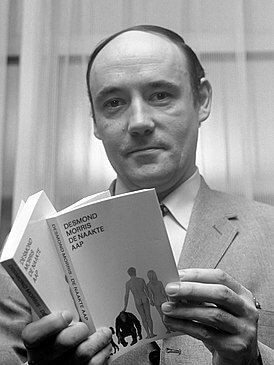

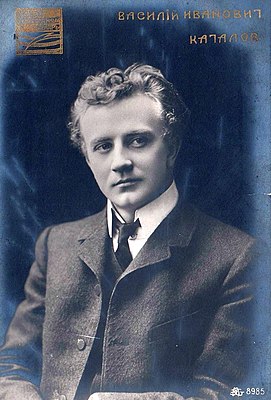

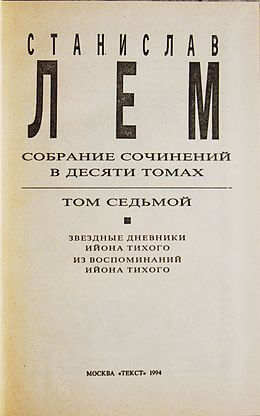

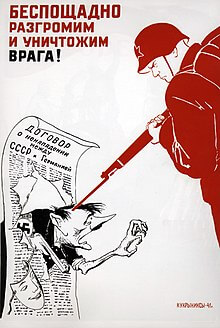

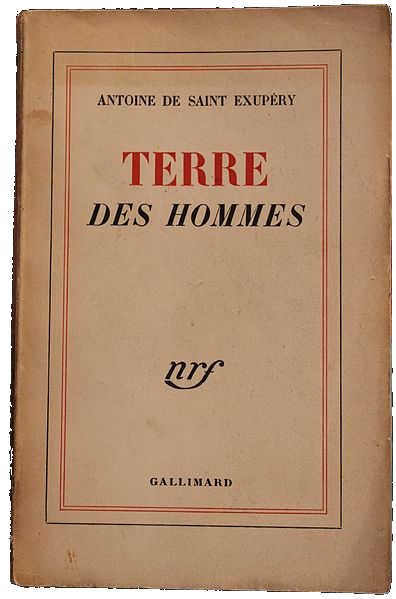

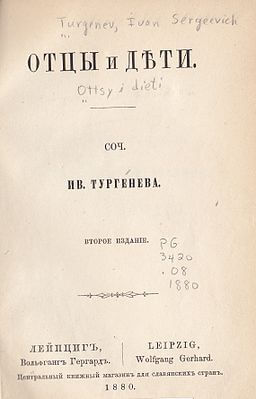

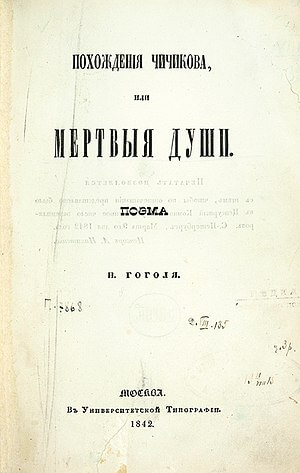

James V. McConnell. Worm runner’s digest

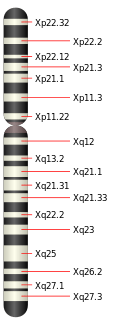

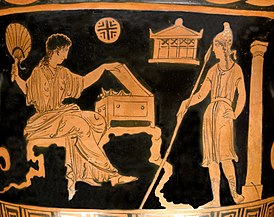

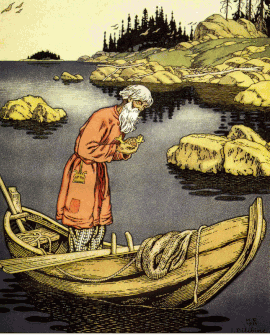

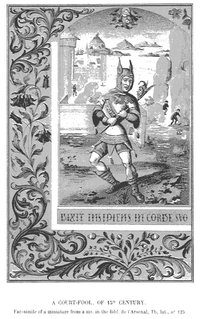

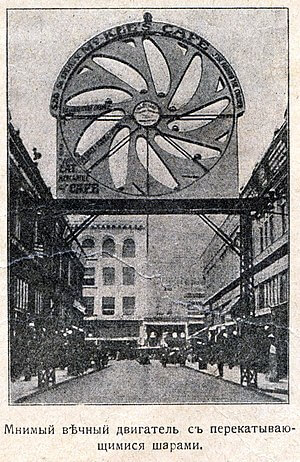

In November, 1959, a curious hectographed journal made its first appearance on the American scientific scene. The first page bore on a heraldic device, a two-headed planarian surmounting a Latin legend that read: Ignotum per Ignotus: The journal is published irregularly, probably only when there is enough copy to fill it, under the leadership of Dr. James V. McConnell, professor of psychology at the University of Michigan. The publication carried a strange name, The Worm Runner’s Digest, an informal journal of comparative psychology.

The infamy of the Digest grew rapidly; greater numbers of interested scientists, educated non-scientists, readers with welldeveloped funny bones, psychologists, physicians, physicists, began calling for copies. It was an odd schizophrenic blend of humor and scientific investigation. This quality has been retained; today, The Worm Runner’s Digest is published in upside — down — front — to — back — tofront fashion. The first half carries sober, sane planarian research. But, turning the book over and reading from the back forward, are the inebriated, insane, delightful spoofs on science and anything else under the sun — usually through the jaundiced eye of a worm runner. There is, according to Editor McConnell, writing in an anthology of satirical pieces from the Digest, a jargon among psychologists. In this, by now well known, jargon, a psychologist working with rats is a rat runner, one who works with bugs is a bug runner, and, it can be assumed, one who works with caterpillars would be a caterpillar runner. Therefore, because of the interest at the Planarian Research Group of the Mental Health Research Institute at the University of Michigan, the name was obvious: The Worm Runner’s Digest was born.

Work with flatworms has led worm runners to a particular worldoutlook, as well as particular personality traits, which may be manifested in various ways. For instance, with a mixture of rue and distaste, Dr. McConnell writes that today, Science stands fair to join Religion, Motherhood and the Flag as a domain so sacrosanct and so sanctomonious, that leg-pulling isn’t allowed, levity is forbidden, and smiling is scowled at.

But, because tradition and over-weening sobriety are two very real enemies of the creative mind, no one who plays with worms for a living, as he and his students and co-workers do, could survive the jibes of his colleagues unless armored by a penetrating insight into the cosmic comicness of this whole affair called science.

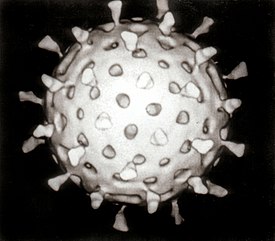

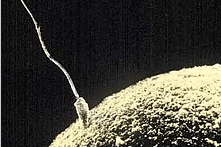

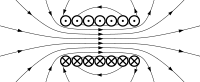

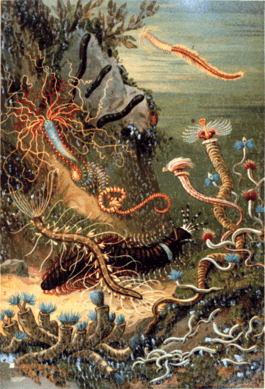

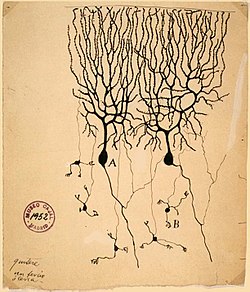

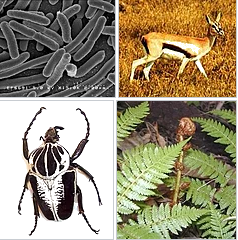

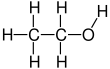

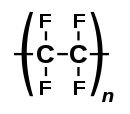

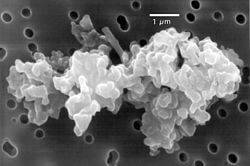

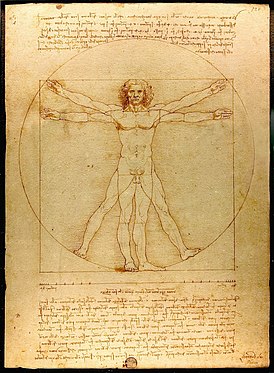

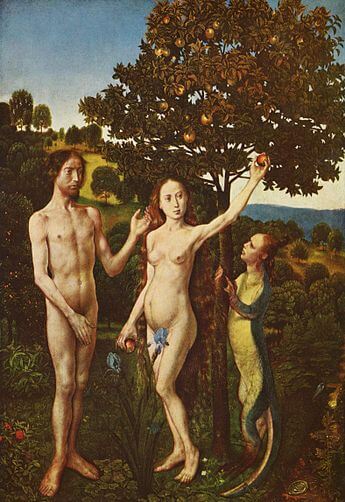

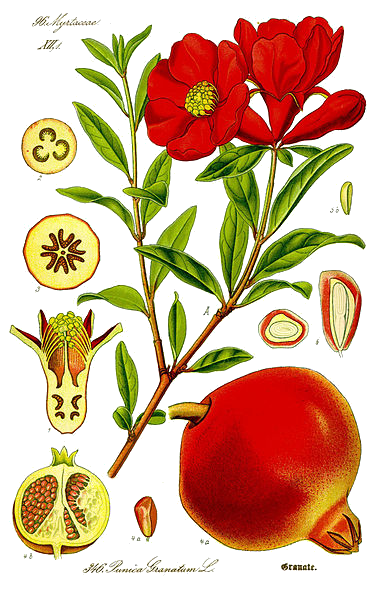

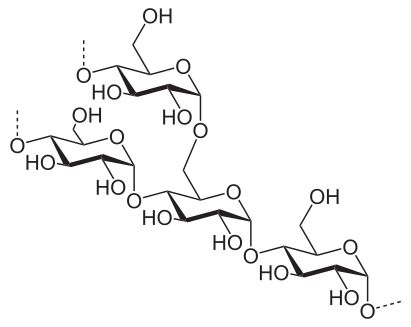

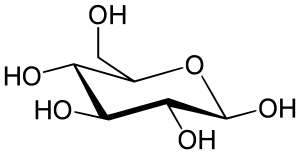

The flatworm used in the research group’s work have a disconcertingly humanoid, cross-eyed appearance, and are about half an inch in length when fully grown. The fascination of these animals derives from the fact that they are the lowest creatures in the evolutionary hierarchy who possess a brain of sorts and a true central nervous system, with bilateral symmetry, but at the same time the highest ranking among organisms which reproduce by fission Arthur Koestler, A New Look at The Mind, London Observer, April 30, 1965.

They may drop their tails at one season; the head section grows a new tail, the old tail grows a new head. They can be sliced into as many as six segments, each of which will regenerate into complete planarians. But, planarians are multi-talented. Hermaphrodites, they function as males in their youth, but in maturity decide they will propagate the race as females, and lay eggs. At one stage in its life-cycle, usually during the mating season, the planarian becomes a cannibal and devours everything it can grab, including its own discarded tail, which has been in the process of growing a new head. |