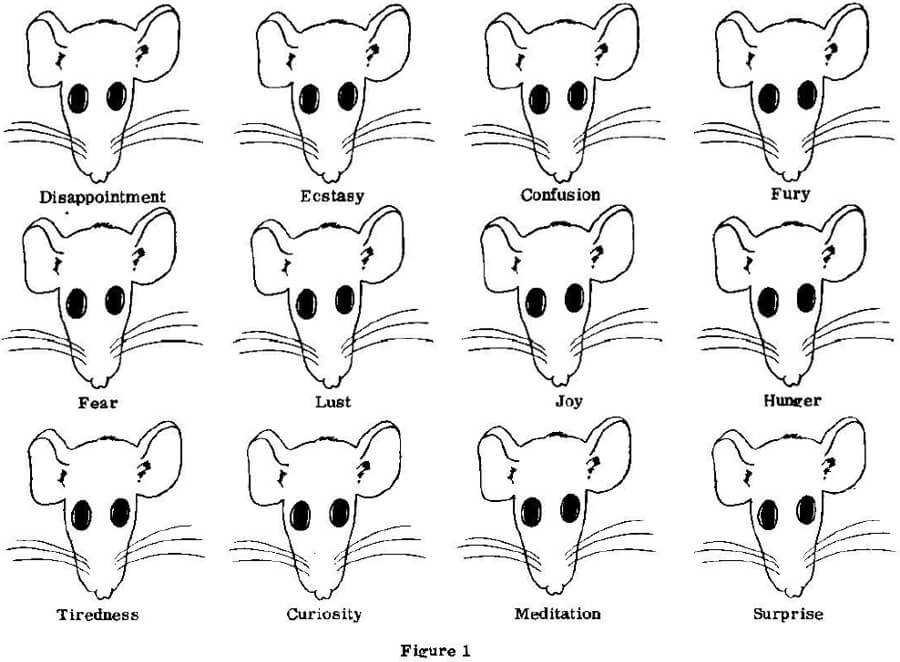

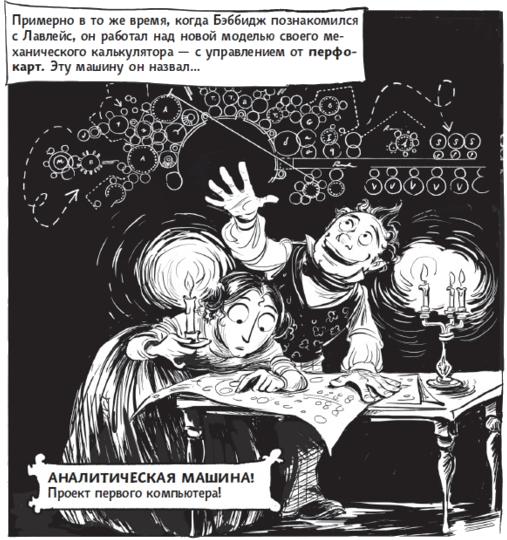

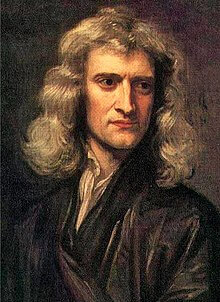

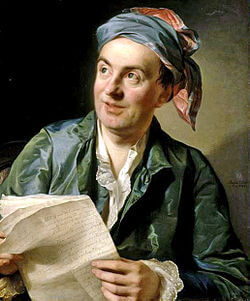

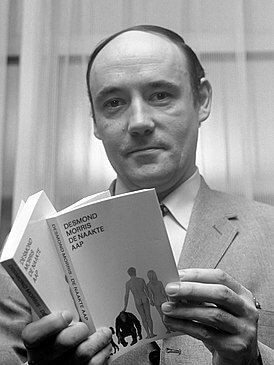

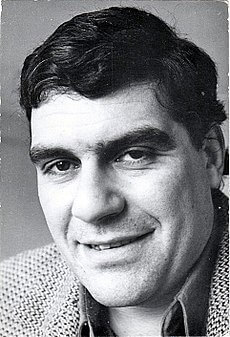

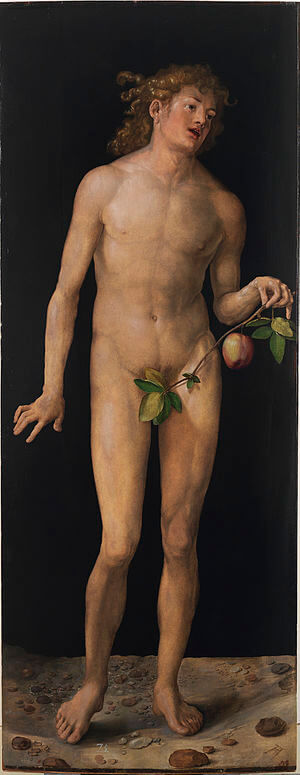

McConnell’s Origin Myth for Planarian LearningMcConnell was a charter member of the Science Fiction Writers of America, and his stories were good enough to appear in magazines for science fiction. In his story, Learning Theory, McConnell is the protagonist who is abducted during the preparation of a lecture on learning theory onto an interstellar labship to become a subject, confined to a series of chambers that resemble the Skinner box, T-maze, and Lashley jumping stand. After first behaving according to the predictions of learning theory, McConnell realizes that he will be returned to Ann Arbor if he misbehaves by violating the predictions of his captors’ theory of learning. McConnell was an iconoclast, and his story is a spoof on learning theory in 1960. After the loss of grant support produced the demise of the planarian research project around 1971, McConnell wrote a very innovative textbook of introductory psychology McConnell. Given his background in science fiction, it was natural for McConnell to blend fiction with the factual material of a textbook. To capture student interest, a unique feature of McConnell’s text was a short story wrapped around the psychological meat of each chapter McConnell. The fictional stories were deliberately written to avoid gender and ethnic bias in language McConnell. For his chapter on memory, McConnell wrote a fictional version of the Thompson and McConnell study called Where Is Yesterday? The heroes of the story were students who were running an experiment on planarian learning. The antagonist was an establishment teacher of the students called Sauerman. These characters were obviously inspired by Thompson and McConnell’s experience with Bitterman. Notwithstanding McConnell’s quotation at the beginning of this article, he rewrote history by cutting Bitterman out of the origins of planarian learning while incorporating into the fictional account the very control Bitterman had required for his endorsement. To readers of McConnell’s introductory textbook, he and Thompson appeared as anti-establishment youth heroes of the 1960s who single-handedly took on the scientific establishment of learning theory from a laboratory in a kitchen sink of an apartment in Austin, Texas, with a budget of $3.89 for equipment and then, somewhat like Horatio Alger, earned fame and fortune with federal research grants. McConnell’s story had a kernel of truth: Planarian learning really did begin in McConnell’s kitchen sink. McConnell gave Bitterman the fictional name, Sauerman. McConnell wreaked his revenge on Bitterman for the low opinion of his article in the following lines: Sauerman hates flatworms.., he won’t let us work in the animal labs… There’s no way to get an A on our project, you know… Doing research that Sauerman doesn’t approve of… might even make us famous. McConnell, 1983, p. 366

Here, McConnell’s fiction deprives Bitterman of the due credit for originally suggesting a planarian preparation. In the fictional study, McConnell demonstrated after a delay of almost 20 years that he really did understand Bitterman’s lesson about the appropriate control groups for classical conditioning. In his fictional version, McConnell added the unpaired control group recommended by his former mentor, Bitterman. This control, actually run by Baxter and Kimmel, was not present in the original Thompson and McConnell study. We’ve got to prove that it’s the pairing of the light and shock that causes any change in the way the worms respond. And the third group gets both light and shock, but they are not paired McConnell, 1983, p. 368

The moral that McConnell chose for the fictional story was a lesson about the importance of control groups. How ironic that McConnell was often accused by critics of running experiments that were poorly controlled!

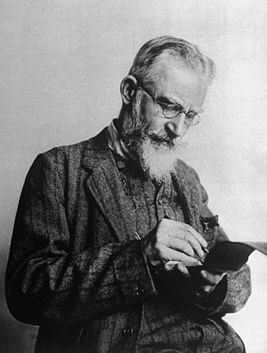

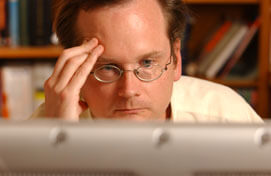

Escaping peer review as a celebrity-scientistMost scientists probably consider their task complete when an article is finally in press. Because the public does not read scientific journals, McConnell believed that a scientist also has an obligation to communicate significant findings to the public through the mass media. Such communication requires skills in public relations, a field in which few psychologists have expertise. McConnell had an edge because he worked in radio and television before his career as a psychologist. He cultivated the press throughout his career as a psychologist, and he thought that professional scientists should cooperate with the press as much as professional athletes. McConnell was not only a scientist, but also a very successful science writer and pop psychologist. McConnell’s media strategy is best described by the person who knew him best, his personal secretary and business manager of The Worm Runner’s Digest, Marlys Schutjer: Jim wanted to say things that would shock people, to create controversy, so as to make people think. He wanted to be controversial. He wanted to get people to say, ‘You’ve got to be kidding!’ He wanted to interest people, but in the end he wound up alienating his colleagues. McConnell, 1983, p. 366

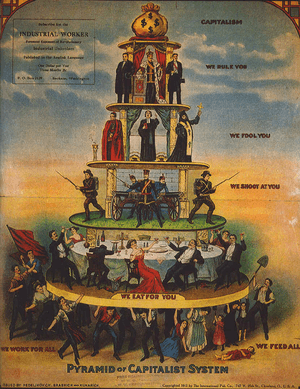

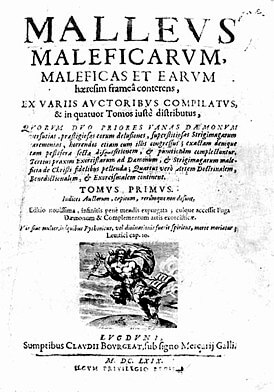

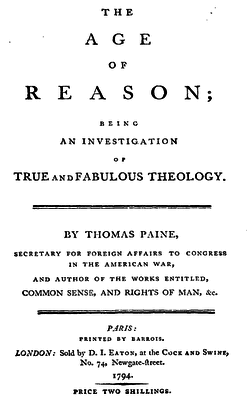

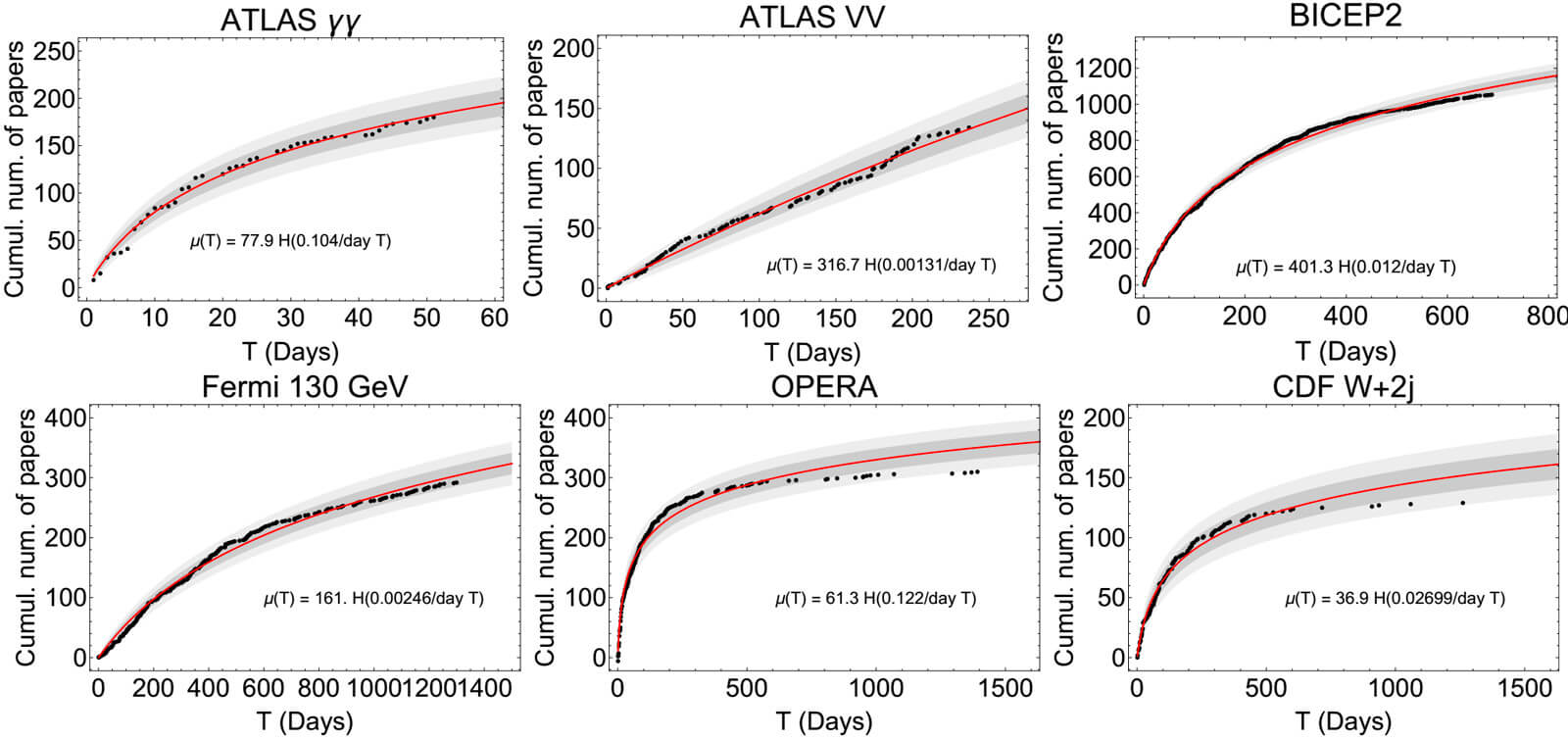

For most scientists, the news is the discovery, the original data presented in the article. Journalists also want to know from scientists about their discoveries, but there is more to news than just discovery. For research on animals, journalists also want to know about potential applications of scientific findings to humans. News sometimes involves predicting the future, so journalists often ask scientists for forecasts. In a modern culture permeated with science, the public expects a scientist to assume the role of a prophet. McConnell was a futurist who believed in a behavioral revolution similar to the industrial revolution, so his media work often contained predictions that went well beyond the data. The problem with scientitlc journalism is that, unlike the editors of APA journals, journalists do not provide peer review. They are not experts on the science. Benjamin‘s work on the history of psychology’s public image from the 1880s through the beginning of World War II revealed that psychologists promised more than they could deliver, a situation that fueled public distrust. The APA has long encouraged coverage of its annual meeting by the media, but Benjamin’s work revealed that, historically, the coverage has often been sensational, a tradition McConnell continued. McConnell’s work on retention following regeneration in planaria provides a case study in sensational journalism and illustrates how his media work escaped the normal mechanisms of peer review. When McConnell submitted an article on retention following regeneration to Harry Harlow, editor of the Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, his cover letter contained the following statement: At the close of the article we permitted ourselves the liberty of making some perhaps wild-sounding conjectures to explain our results. I hope that you will not find them too wild, nor out of place in your journal. McConnell, letter, January 27, 1958.

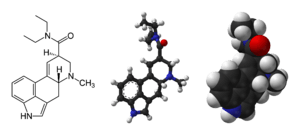

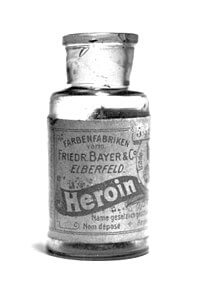

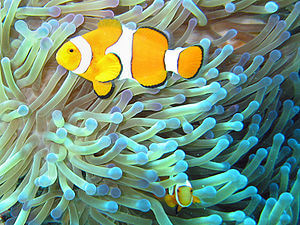

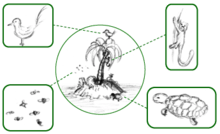

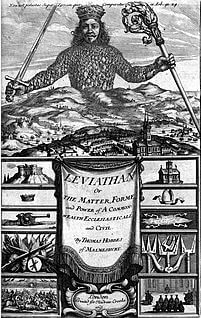

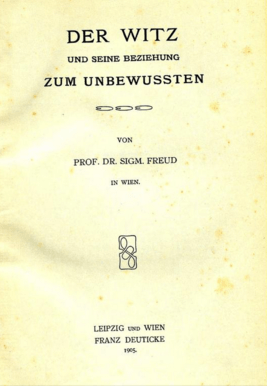

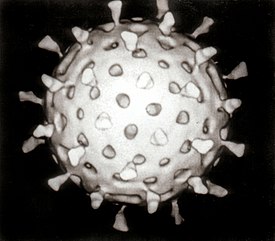

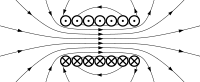

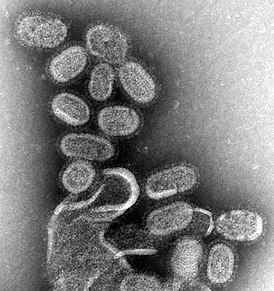

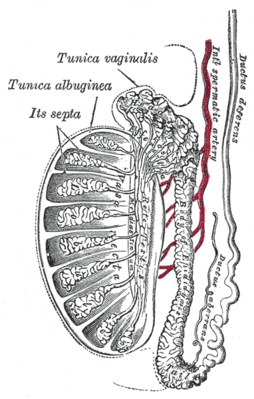

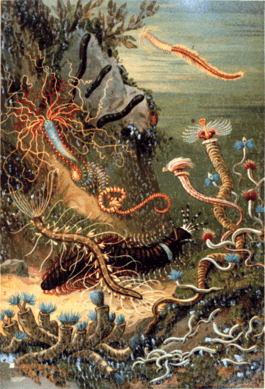

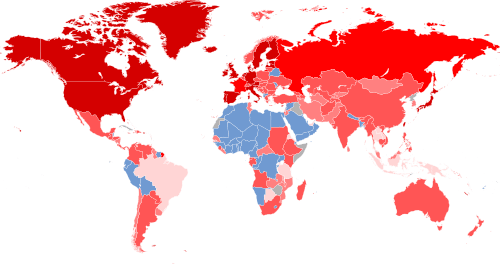

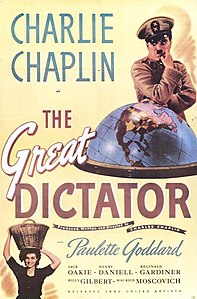

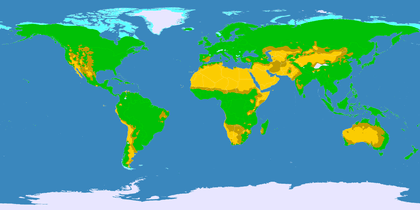

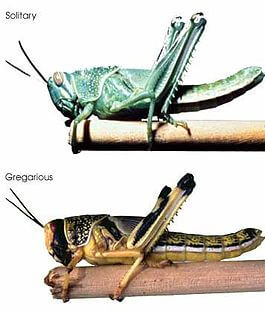

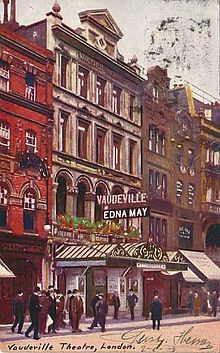

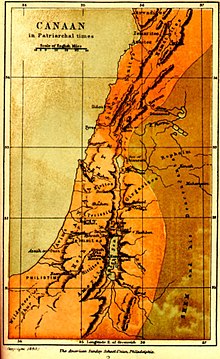

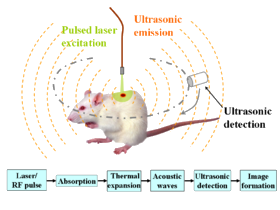

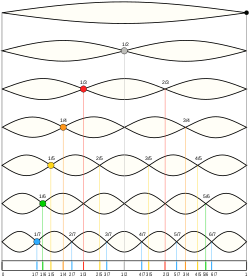

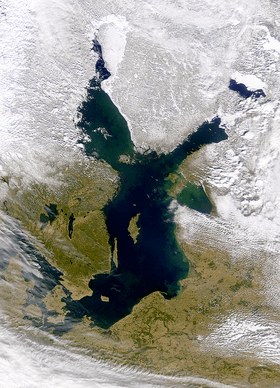

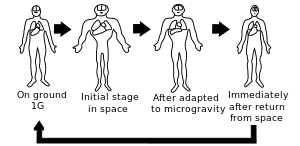

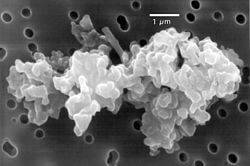

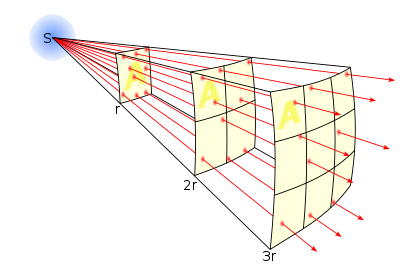

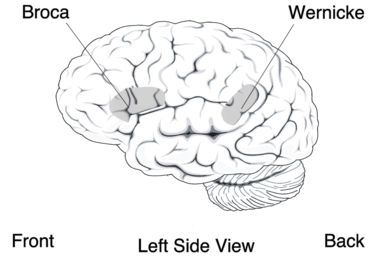

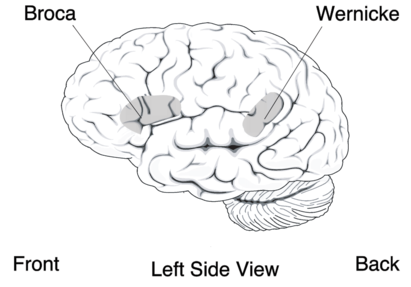

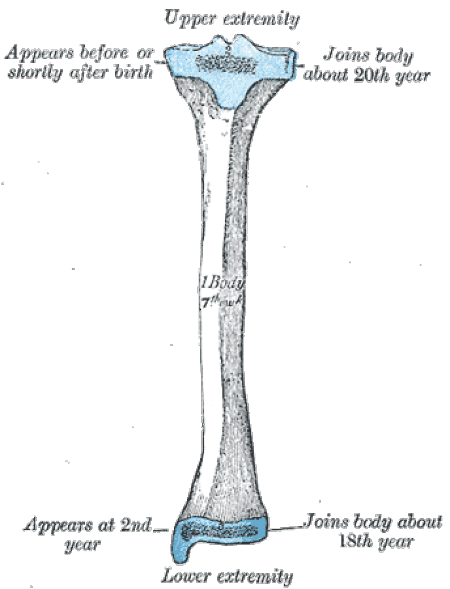

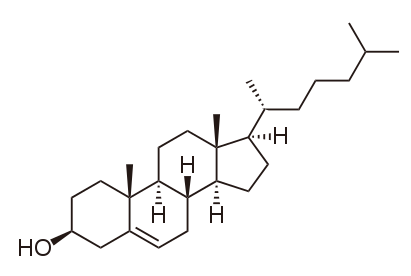

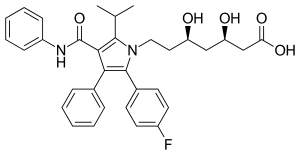

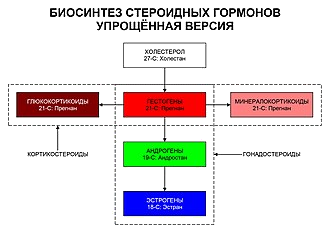

In his acceptance letter, Harlow gracefully insisted that McConnell delete the speculative material from the discussion so as to comply with journal policy. Thus, peer review restricted McConnell’s ability to speculate in the pages of the journals of the APA. The irrepressible McConnell sought other venues for speculation. The annual APA meeting in 1959 provided an opportunity. How did McConnell catapult an arcane topic in comparative psychology, retention following regeneration in planaria, to an international news story? First, for the audience of psychologists, he speculated about a memory molecule; then, for the press, he speculated about a memory pill. When a planarian is cut in half, each half regenerates in about two weeks to form two regenerated planaria. After cutting a planarian in half, the head was conditioned. Repeating the surgery twice, on first- and then on secondgeneration animals, produced a third-generation planarian in which the nervous system was entirely regenerated compared with the organisms that experienced Pavlovian conditioning. When the third-generation animals regenerated from the tail showed savings, McConnell concluded that the engram was biochemical, not neural as Lashley had supposed. The headline for the story became How Tails Remember. Just a few weeks after the APA meeting, Newsweek ran a prominent story indicating that McConnell had discovered that memory and learning appear to have a chemical inherited basis. McConnell never mentioned applications to humans in his talk, yet the readers of Newsweek were promised that It may be that in the schools of the future students will facilitate the ability to retain information with chemical injections. McConnell later recalled the Newsweek story as a a tongue in cheek article, a joke not shared with his readers. McConnell’s next big break in scientific journalism was provided by Arthur Koestler, the British novelist, social critic, and scientific journalist. Koestler and McConnell became friends when Koestler visited Ann Arbor on a personal quest for an experience of LSD. Koestler had a bad trip with LSD, but he was impressed with McConnell. Koestler was one of the 20th century’s great writers, and he wrote a superb article for the London Observer that was reprinted in the United States in The Washington Post. For scientists, the news was that invertebrates could learn, but inherited memory, not learning, was the element of the story that was emphasized by Koestler and the media. The figure for the story had the following caption: How a Worm’s Tail Inherits Memory: University of Michigan Researchers Use Flatworms to Demonstrate How Learning May Be Inherited. In The Washington Post, the headline for the study was Michigan Crawlers Are Crossing Up Mendel and Some Genetic Heresies Are Suggested by Experiments in Ann Arbor. The media wrapped planarian learning with a bizarre cachet about inherited memory. The public was not let in on the inside s tory — that language McConnell borrowed from genetics about successive generations was metaphorical, so a casual reader could easily have been misled into believing a story about a Lamarckian inheritance of acquired characteristics. In 1964, the Saturday Evening Post, the magazine of middle America, carried a feature story on McConnell. By 1964, McConnell had moved from regeneration to cannibalism, so now the public relations effort switched to the new work on memory transfer. The magazine told readers that uneducated worms can acquire the wisdom of more intellectual ones by eating them. This suggests a theory of knowledge which, avoiding outright cannibalism, might someday enable us to learn the piano by taking a pill, or to take calculus by injection p. 66.

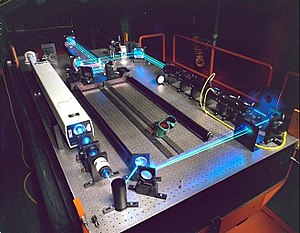

McConnell was one of the first psychologists to recognize the potential of radio and television for public education. Prior to receiving his PhD, McConnell worked in radio and television as a disc jockey and script writer. During the 1960s, Steve Allen was one of the pioneers of the television talk show. His shows were seen by millions. The script for McConnell’s appearance on the Steve Allen Show was simply a televised version of the McConnell story in the Saturday Evening Post. McConnell carried his apparatus to Los Angeles for the taping, so millions of viewers heard a lecture from McConnell about Pavlovian conditioning in invertebrates. However, the price for communicating the basic science was packaging the top and bottom of the show with wild science-fiction speculation about memory pills, predictions about the future of man, and showbiz hype. McConnell was extremely skillful in calibrating his rhetoric to his diverse audience, even to the extent that his scientific writing and private letters to individuals sometimes contradicted the impression left by his media work. McConnell generalized freely from planaria to humans when his audience was the readers of Time, Newsweek, and the Saturday Evening Post. When writing for a scientific audience, he cautioned that one obviously should not generalize these results to the human level too readily. Although McConnell’s media work made it appear that memory pills were just around the corner, individuals who wrote to McConnell requesting information on where to obtain memory pills received a very conservative, cautious form letter, which stated that the memory molecule is merely an assumption on our part… At the moment, there is no such thing as a memory pill, McConnell’s strategy of publicity at any price was a double-edged sword. The publicity probably attracted some scientists to planarian learning, but McConnell’s flair for speculation put him on the fringe of scientific respectability. Evaluating McConnell’s public relations blitz for planarian learning and memory from the vantage point of 30 years is difficult. To market his ideas to a mass audience, McConnell connected planarian learning to the American myth of the quick, easy, simple technological fix for complex problems. McConnell knew when he was kidding, but his less sophisticated mass audience could easily have been misled. By appealing directly to a mass audience, McConnell escaped the peer review that would have tempered his hype. He outmatched the few dissenters with charisma. The profession does not have a mechanism for providing peer review for the attempts of psychologists to popularize the discipline. Because psychologists have a First Amendment right to express their views on psychological topics to the public as they see fit, the problem of how to popularize psychology does not have a simple solution. Fidelity to the peer-reviewed literature is proposed as an ethical standard for evaluating coverage of psychological topics by the media. When a topic is controversial, the media could present alternative viewpoints, dissenting opinions, and heavy doses of old-fashioned scientific skepticism. The coverage of planarian learning by the media provides lessons of contemporary relevance. Although the coverage of contemporary neuroscience by the media is well beyond the scope of this article, basic research on neural mechanisms of memory is still sometimes accompanied by speculation about a memory pill. Our graduate institutions do not provide psychologists with training in the art and ethics of public relations. This represents a failure to build public support for science. Many responsible psychologists shun the media and are even reluctant to cooperate with professional science writers because of a desire to avoid the sensational. By their silence, such scientists bear some responsibility for the distorted messages about psychology that reach the public through the media.

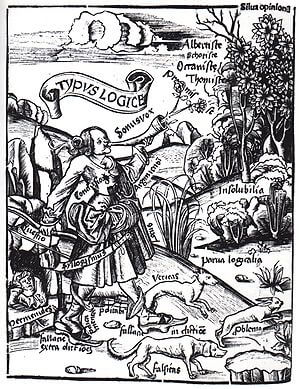

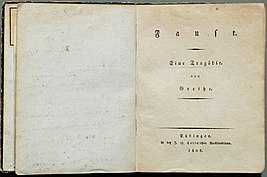

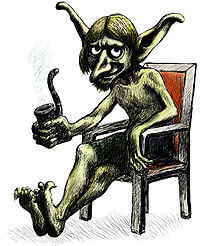

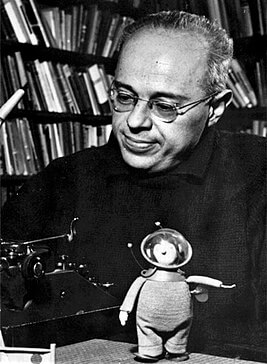

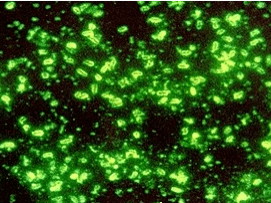

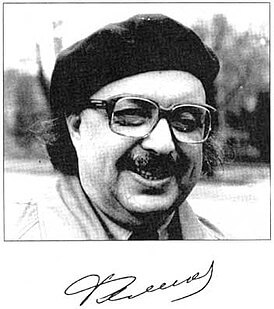

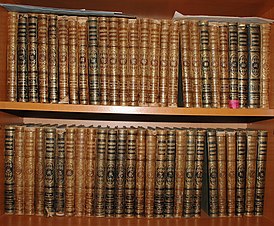

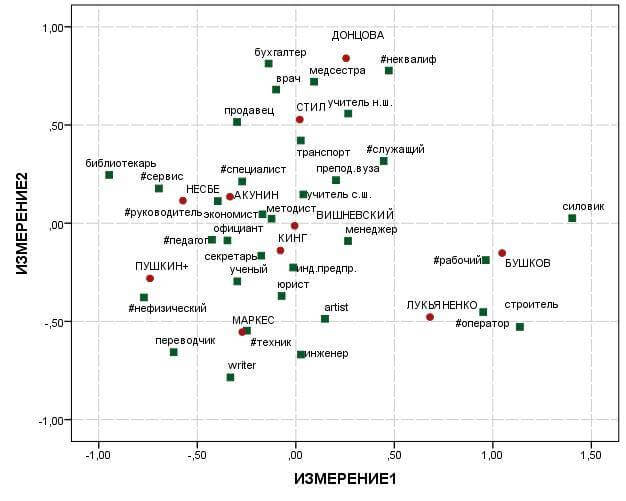

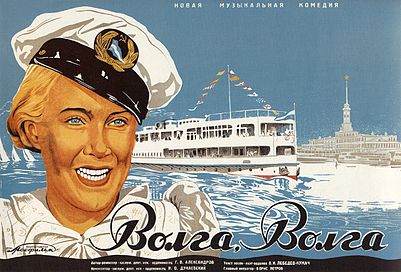

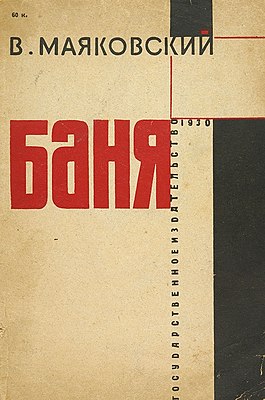

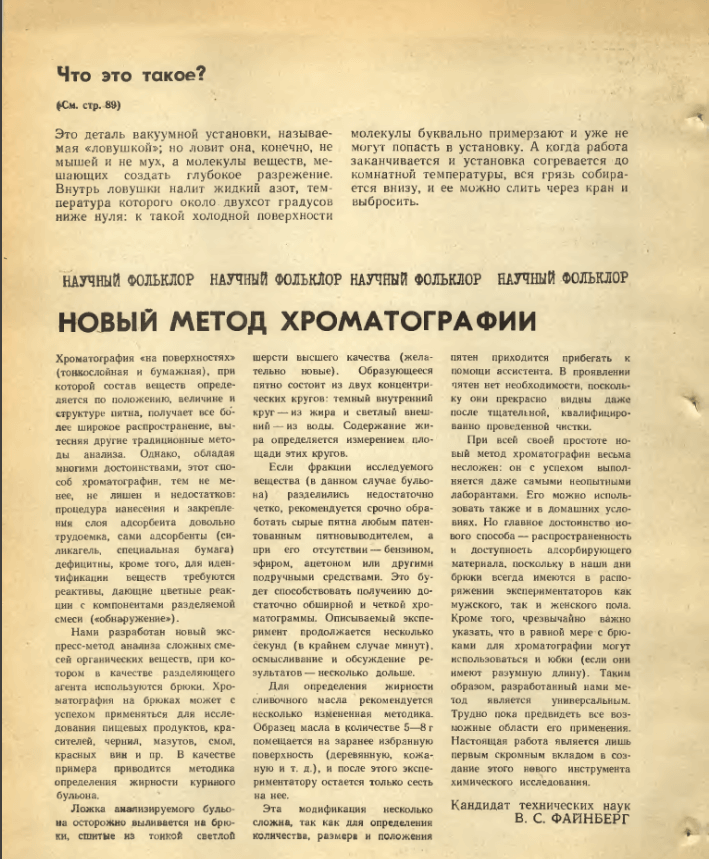

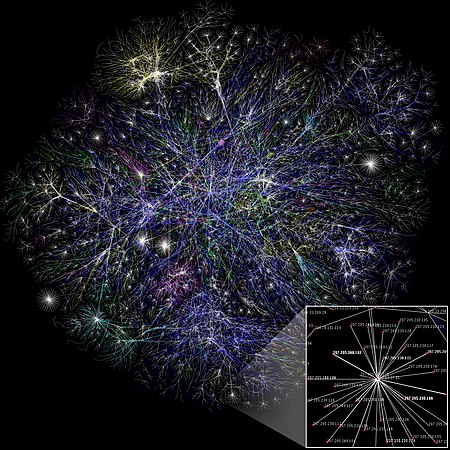

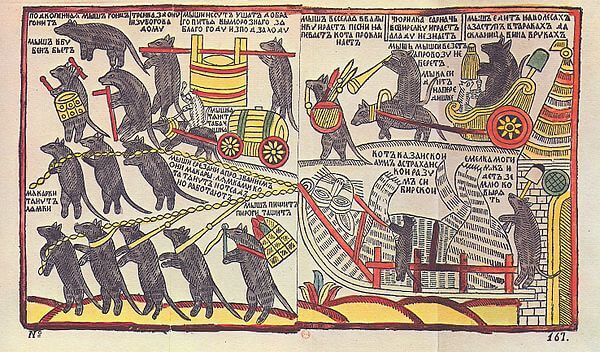

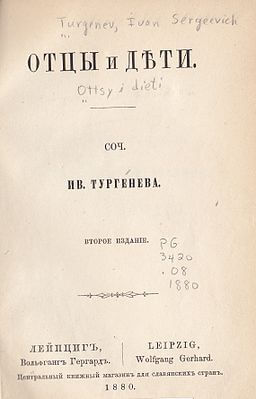

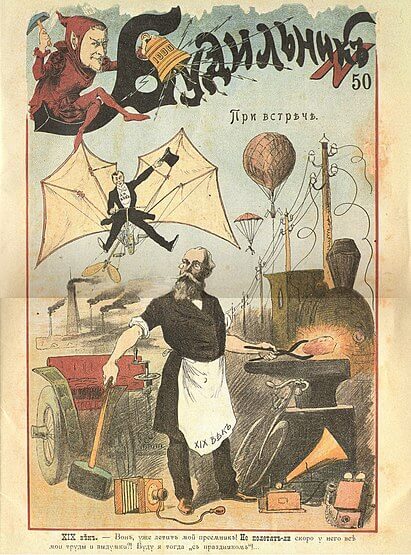

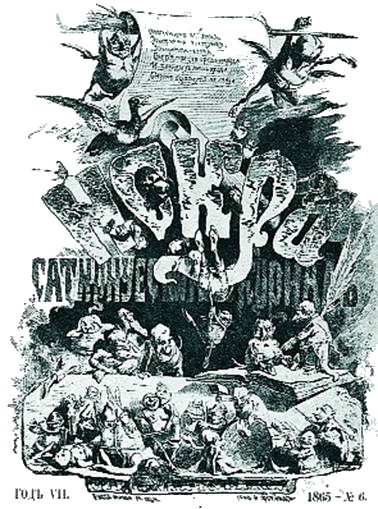

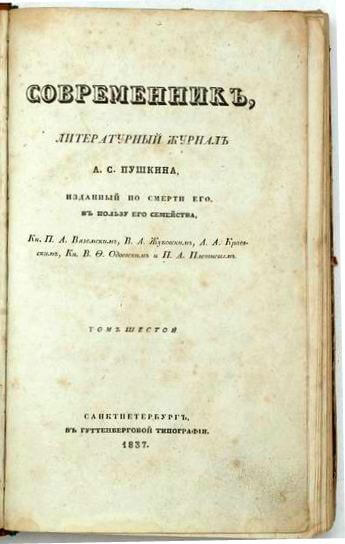

The Worm Runner’s Digest: Peer Review Versus the 1960s CountercultureMcConnell’s name is inevitably linked with the infamous The Worm Runner’s Digest, McConnell’s house organ. Today McConnell would have set up a Web site on the World Wide Web, but there was no Web site in McConnell’s day, so he founded his own journal. The journal is hard to pigeonhole. It is funny and strange: an improbable, flawed, and ultimately unworkable combination of a humor magazine and a scientific journal. It is one of the great cultural relics of psychology from the 1960s, a scientific incarnation of the counterculture. Cmiel, a social historian of the counterculture of the 1960s, analyzed the rhetoric of the counterculture and observed that it represented an attack on the prevailing norms of discourse. For McConnell, the rhetoric of the scientific establishment was serious, so as an antiestablishment scientist he countered with humor. The Digest was a counterculture version of the Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology and was born in the burst of public enthusiasm for planarian learning that followed the story that appeared in Newsweek in September 1959. Below the masthead, the digest was identified as An Informal Journal of Comparative Psychology. The idea was to provide a clearinghouse for research with planarians, that is, to publish pilot studies before final versions were published in traditional scientific journals. At first, a clear consequence of McConnell‘s editorial policy was that articles would escape the rigorous peer review of the establishment journals. After the Digest was founded, McConnell never again published an article in the Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. The Digest soon became a home for memory transfer research. At first, the ideas about memory transfer that McConnell placed in the Digest were taken very seriously by other scientists until failure to replicate letters and articles in Science consigned memory transfer to the scientific fringe. In addition to the serious science, the Digest was clearly part of a counterculture effort to poke fun at the scientific establishment. The masthead of each volume of the Digest included a shield with a two-headed planarian, below which was a Latin inscription Ignotum per Ignotius, translated humorously as the unknown explained through the still more unknown. The problem was that as the head of the Planarian Research Laboratory at one of the finest research institutions ever assembled and as a scientist whose research grants were subsidizing the Digest, McConnell was attacking himself because he was part of the scientific establishment. The scientists who published the serious articles in the Digest wanted to receive credit from others for their work. Citation by others is one of the clearest ways of providing credit. One issue that surfaced early was Does one dare cite an article from The Worm Runner’s Digest? (McConnell, 1960, p. 3) in a peer-reviewed journal. For some editors, the answer was clearly no. McConnell was never able to achieve a satisfactory resolution between his sense of humor and his sense of science. McConnell’s first solution was to put the serious articles at the beginning of the journal and the satire at the end. When the serious authors of the scientific articles complained that abstracting services refused to consider citation for any article that appeared in a journal with such a strange title as The Worm Runner’s Digest, McConnell twinned the journal. The front half was called The Journal of Biological Psychology, but the back half, which was published upside down, was The Worm Runner’s Digest. Suddenly, libraries wanted to subscribe to The Journal of Biological Psychology, and Psychological Abstracts requested a copy of this new journal for abstracting. By 1967, McConnell announced a policy of peer review for both journals; thus, even McConnell was forced to adopt a policy of peer review. McConnell poured thousands of dollars over the years from his own pocket to keep the Digest alive, so the journal represented a financial loss for him. In his closing editorial, he recognized that it is impossible to publish a journal these days without the backing of some organization. McConnell was a precursor of the neuroscientists who took up the biochemistry of memory where he left off. McConnell only got inside his organism with biochemical rhetoric, never with a valid neurophysiological technique. Today planaria are no longer used in research in the biochemistry of learning, so McConnell’s planarian learning program represents the end of a line. However, the torch of the search for the engram was passed to the next generation. The location of the books in the library at Michigan State University provides a metaphor for this historical transition. The Worm Runner’s Digest was passed to history when it ceased publication in 1979. In this library, a few feet away from the last volume of the Digest, is the first volume of The Journal of Neuroscience, which began publication in 1981. No one could ever confuse The Journal of Neuroscience with a humor magazine. That journal was published by the Society for Neuroscience, and in its first volume there was an article on classical conditioning of a simple withdrawal reflex in the invertebrate, Aplysia californica, by Carew, Waiters, and Kandel. After a quarter of a century, this article is a worthy successor to Thompson and McConnell‘s first article on planarian classical conditioning. There is no reference to McConnell or the controversy over planarian learning, but Carew et al. followed in McConnell’s footsteps with the following procedures: visual observation of the dependent variable; five control groups, each of which had been used earlier in invertebrate learning; and the testing, which was carried out using a blind procedure. The lessons from the planarian controversy had been mastered by those who were about to write the next chapter in the search for the engram by watching siphons withdraw instead of planaria turn. With settlement of the invertebrate learning controversy by the specification of control groups, McConnell liberated the next generation. The dream of a Nobel prize for unraveling the biochemistry of memory now belongs to a new group. | Как написать статью, которую не примут в англоязычный журнал — 24 совета Статья написана по мотивам Kenneth D. Mahrer- Пишите на ломаном английском через пень-колоду – так, чтобы никто ничего не понял. Дружно плюем на грамматику английского языка с высокой колокольни. Понапридумывали там у себя в Англии времена дурацкие, да причастия всякие. Нефиг их баловать! При этом попытайтесь изложить материалы статьи, как можно бестолковее.

- Никогда не приводите в статье всех данных о своих результатах или алгоритмах. Иначе, найдется чудак, который обязательно захочет их проверить.

- Никогда не объясняйте в статье предположения или ограничения, на которых построена ваша модель. А то найдутся крючкотворы, которые брякнут, что модель-то работать не будет!

- Не забивайте себе голову мыслями, что ваши модель и данные не согласуются друг с другом. Зато, какая красивая картинка получилась!

- Пишите аннотацию как можно короче или так, чтобы никто ничего не понял. Без этого вашу статью всё-таки могут принять в журнал. А лучше вообще вставьте пару строк, которые не имеют к вашей статье никакого отношения. Запутайте читателя сразу – во введении. Сделайте его куцым и совершенно непонятным.

- Запутайте читателя сразу — во введении. Сделайте его куцым и совершенно непонятным.

- Оторвитесь в резюме статьи! Напишите его так, чтобы наивный читатель буквально позеленел от злости, поняв, что он только зря потратил время на ваш опус.

- Содержательную часть статьи лучше писать казённым, скучным языком, огромными предложениями, с кучей деепричастных оборотов. Пусть читатель уснёт крепким и здоровым сном уже на второй минуте.

- Не думайте о каких-то там читателях! Пишите статью для себя и своей мамы. Уж мама то будет рада любой вашей галиматье – лишь бы ребенок не хулиганил! Также не стоит показывать написанную статью неспециалисту или не совсем специалисту. А то еще услышите: Что это за фигня!

- Как можно сильнее запудрите мозги возможному читателю. Никогда подробно не объясняйте основную идею. Обязательно включите в статью материалы, которые не имеют к этой идее никакого отношения.

- Как можно подробнее развезите математические выкладки или описания алгоритмов. Обложите читателя формулами, желательно 3-х или 4-этажными, чтобы за ними потерялся весь смысл того, о чём вы хотели рассказать.

- Никогда не начинайте подраздел статьи с краткого плана изложения и причин его появления в статье. Иначе читатель быстро смекнёт, о чём ваша статья.

- Желательно закончить статью как-бы на вздохе, без обобщения наиболее важных моментов статьи. Пусть подумают, что вас в это момент подстрелили…

- Структуру статьи лучше всего запутать. Высший шик – вообще перепутать разделы статьи между собой! Или, начать во здравие, а закончить заупокой!

- Не медлите ни минуты с отправкой статьи в журнал. Как только вы шлёпнули по последней клавише, тут же распечатывайте, и отправляйте через канцелярию. Перечитывать – лишнее. Иначе вы стопудово обнаружите ошибки. Совсем лишнее – это дать статье отлежаться, как минимум неделю, на полочке. В этом случае в вашу голову может закрасться крамольная мысль: А нафига я вообще написал эту ерунду? Или вы найдете в ней такую кучу ошибок, что никогда бы ее не отправили.

- Отбросьте в сторону сомнения о том, что кто-то что-то уже написал по этой теме. Подумаешь, что эти результаты описаны 20 лет назад! Мысль не ржавеет! Особенно ваша. Пусть радуются вашей статье уже по факту ее появления! Оригинальничать с новизной не стоит. Можно писать и о том, что пережёвывается в журналах уже много лет. Считайте читателей идиотами, ни черта не смыслящими в вашей работе.

- Поскольку все обязаны досконально знать о полученных вами ранее результатах, никогда подробно о них не пишите. Если и давать ссылку, то не нужно утруждать себя такими мелочами, как номера страниц. В конце концов, пусть читатель пороется в паре сотне страниц. Ему же всё равно делать нечего!

- Описывайте полученные результаты с некоторой долей небрежности, оставляя читателю простор для воображения. Неплохо бросить фразу о том, что приведенные результаты составляют сущность вашего изобретения, и поэтому не могут быть полностью раскрыты. Читатель сразу же проникнется к вам глубоким уважением и признательностью за возможность пофантазировать.

- Избегайте четких и кратких формулировок, когда пишите статью. Подпустите туману. Лучше всего использовать такие фразы, чтобы вас можно было понять и так, и эдак. Это же интересно! Пишите статью в своем неподражаемом стиле, чтобы никто ничего не понял. Поток мыслей должен быть при этом бессвязным. Это запоминается и вызывает дополнительные эмоции.

- Не обращайте внимания на замечания рецензентов. Это – злые люди и ничего не понимают в вашей науке. Поэтому никогда не переделывайте свою статью! На просьбы рецензентов или редактора пересмотреть статью, лучше всего ответить презрительным молчанием!

- Никогда не посвящайте статью какой-нибудь одной идее. Нужно вывалить на читателя целый ворох своих идей, методов и рассуждений. Пусть оценят ваш интеллект в полной мере!

- Сложно писать предложениями на целую страницу, поэтому попытайтесь писать предложениями хотя бы на треть машинописной страницы.

- Не следуйте профилю и тематике журнала. Как, впрочем, и требованиями журнала к оформлению статей. Это скучно.

- Круче всего – это когда в статье отсутствует вообще какая-нибудь идея! Это класс! Удаётся это немногим, но всё же, постарайтесь!

Материалы Ann-Arbor District Library

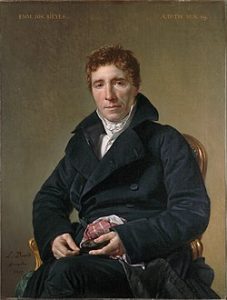

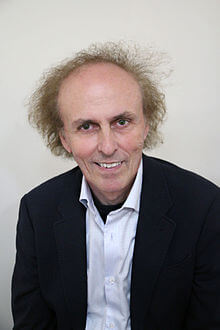

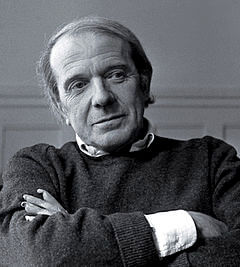

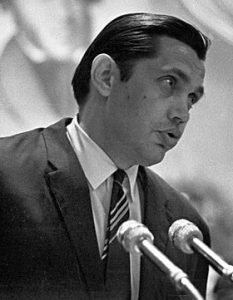

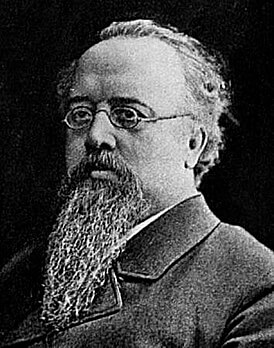

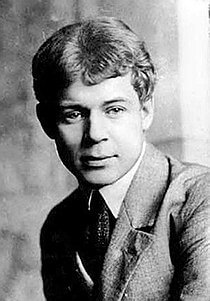

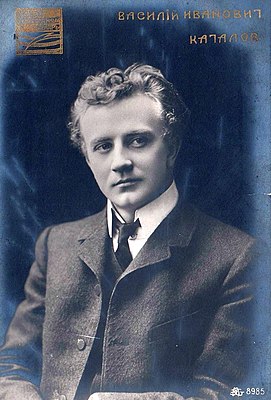

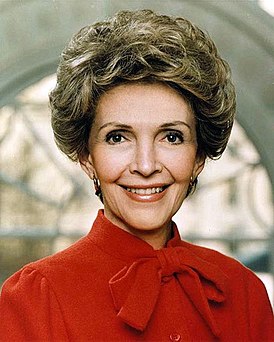

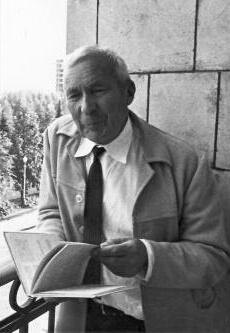

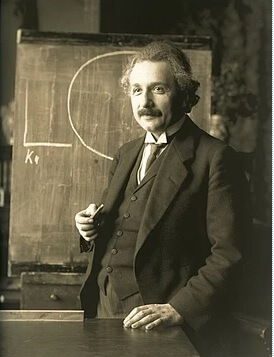

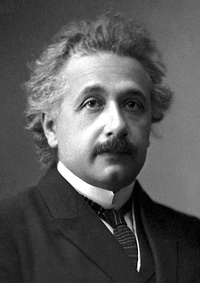

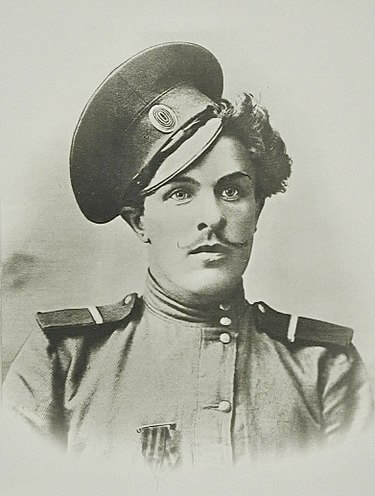

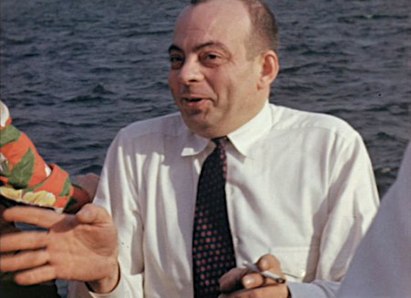

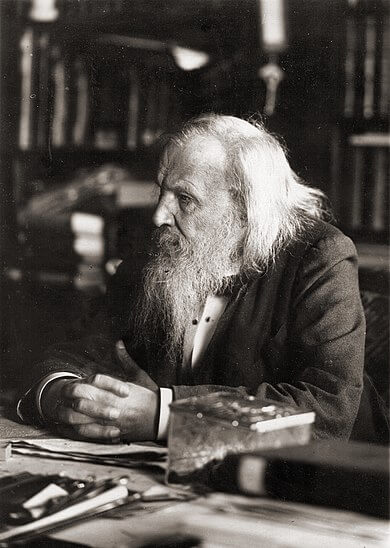

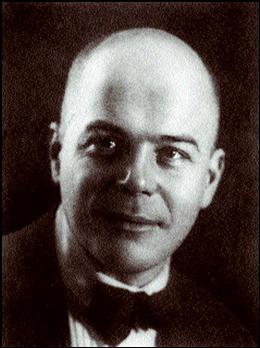

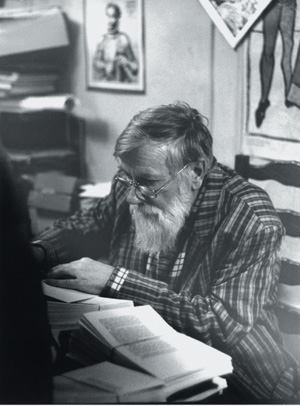

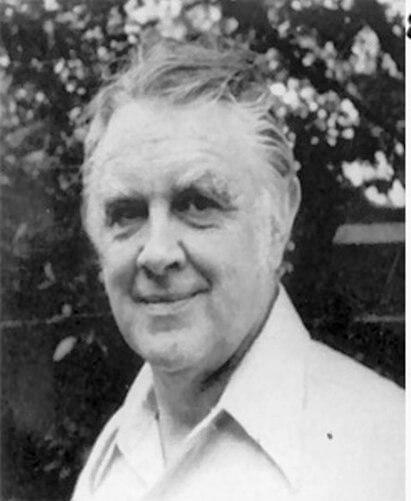

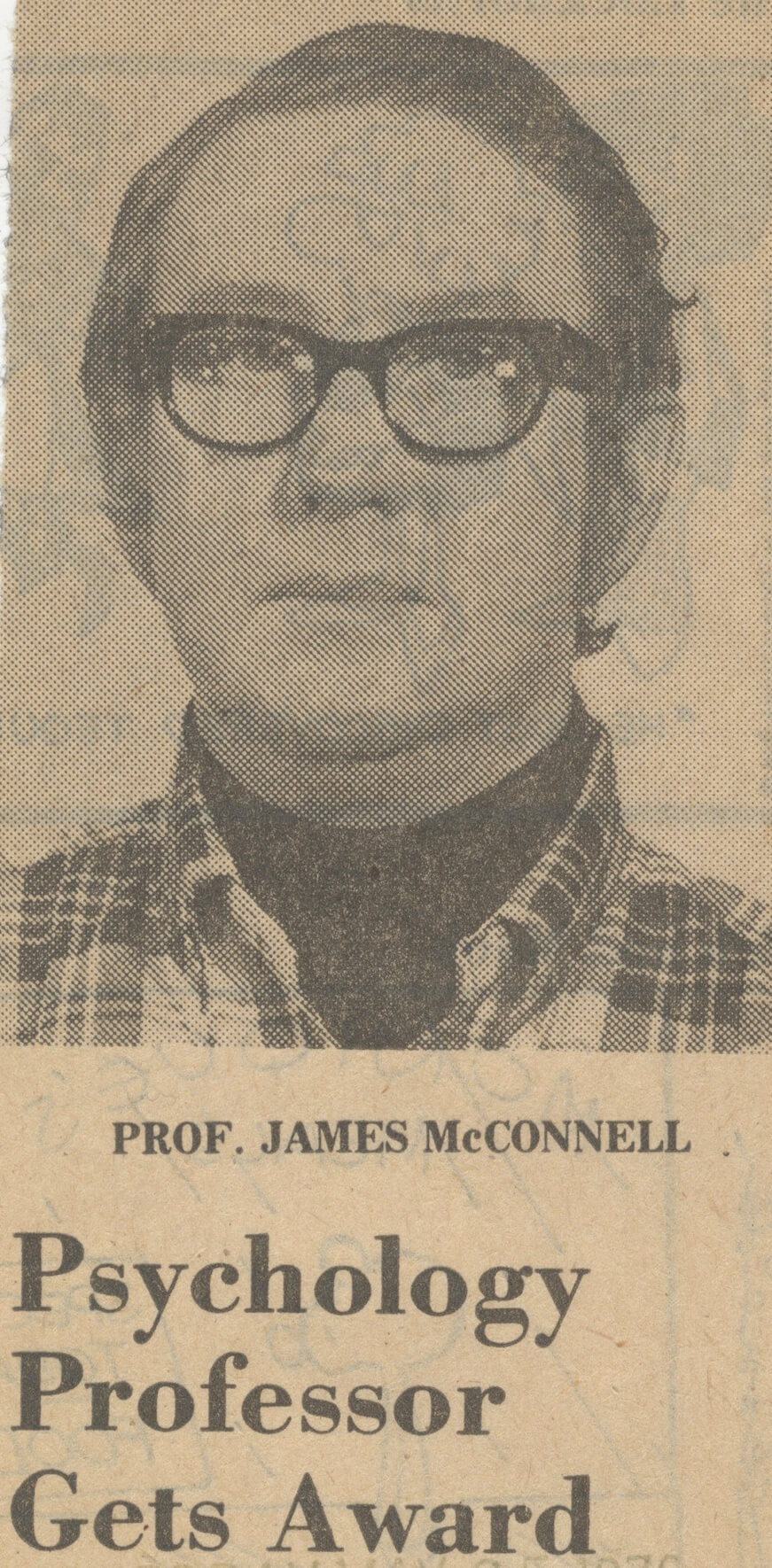

U-M psychology Prof. James V. McConnell will receive the American Psychological Foundation’s annual Award for Distinguished Teaching in Psychology for 1976.

The award including a check for $1,000, will be officially presented at a dinner ceremony Sept. 4 during the Foundation’s annual convention in Washington D.C.

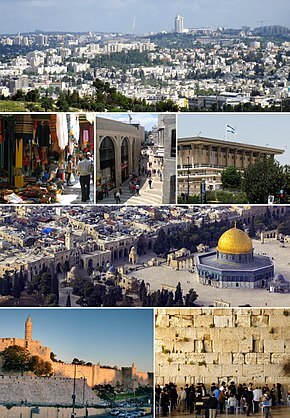

McConnell joined the U-M faculty in 1956, and has been a full professor in psychology and research psychologist with the U-M Mental Health Research Institute since 1963.

The teaching award closely follows McConnell’s recent selection as one of 26 outstanding college and university teachers by Change Magazine. McConnell has attracted national attention for his undergraduate psychology course, Introduction to Behavior Modification, in which U-M students have successfully worked as behavior therapists in area mental hospitals, schools, prisons and other institutions.

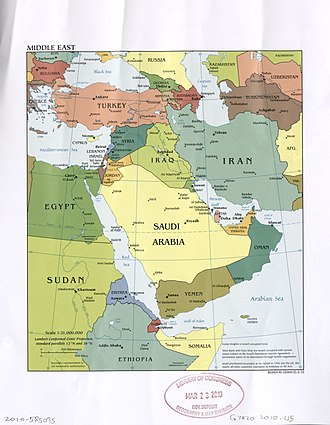

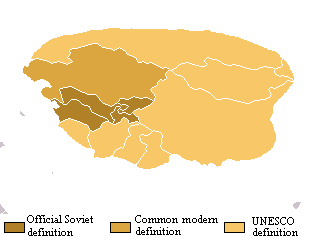

He is also known as the founder and editor of the humorous scientific magazine, The Worm Runner’s Digest, whose origins he describes in the current issue of The UNESCO Courier, an international monthly publication of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

Published as a joke in 1959, the Digest immediately drew serious as well as satirical contributions, and today the publication divides the two carrying a second title of The Journal Biological Psychology.

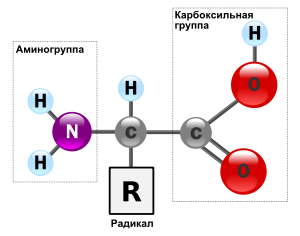

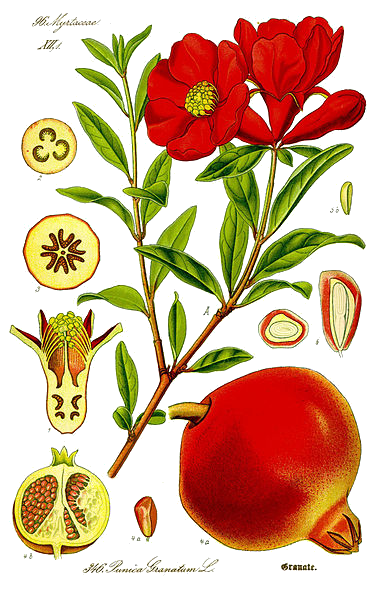

The Worm Runner’s Digest derived its name from McConnell’s landmark planaria research. In the late 1950’s, he found that could be transferred, via the chemical RNA in cells, by feeding pieces of trained flatworms to untrained flatworms. The findings continue to influence national research on RNA and memory.

McConnell, who has written extensively in both the professional and popular press, is also the author of Understanding Human Behavior, an introductory psychology textbook published in 1974 and currently in use by more than 300 college and university campuses. Текст публикуется по The Ann Arbor News Cal Samra. New Publishig House formed: He deals in controversy

A new publishing house called Planarian Press has been formed locally by a U-M psychologist in order to bring to the reading public those books so controversial that many people would cry for their suppression.

One of house’s first productions is a book called The Law Unto Themselves, the case histories of troubled policemen put together by a police psychologist who gave them psychotherapy. The author is clinical psychologist Peter R. Runkel.

Planarian Press has been organized by Prof. James V. McConnell of the U-M Psychology Department, who is editor of The Worm Runner’s Digest, with the intension of publishing controversial books so important in content that they deserved to see print despite the hue and cry their printing would raise.

And The Law Unto Themselves is undoubtedly controversial, so controversial in fact that for seven years Runkel sent the manuscript around to various established publishers and none of them, he says, had the courage to print it.

Over the years, Runkel says he has performed psychotherapy and maintained friendships with hundreds of policemen. He tape-recorded many of the sessions, and this book contains his verbatim converations with 11 cops. The book is fantastic, says McConnell, put together by one of the wisest, most humane madmen I’ve never met.

The author is not at all unsympathetic with police officers. In fact, he counts many of them as his friends, and he explains he wrote the book because the ranks of those hostile to the police appear to be growing, and few voices have been raised in their support.

It may, of course, be debatable whether the police will welcome Runkel’s support.

Runlel says he merely intended to show that police are human beings, vulnerable to all of the doubts, anxieties, and frailties that plague other mortals. Police unlike eggs, says Runkel, do not come prepackaged in cartons of a dozen each, all Grade-A, medium. Policemen are like the rest of us; each is a man unto himself … For some reason, police seem to be in season at this moment of crisis within our national institutions … This sort of all-inclusive condemnation of police is surely not going to get us anywhere … I’m tired of reading about the New York police or the California police, or the Colorado police do not exist. Each officer on each police force is a man unto himself — endowed with his own inheritance of intelligence and his own brand of morality. Our police are men and it is as men that they must be judged, individually, and separately, as each of us wants to be judged — if, indeed, it is for any of us to judge our fellowmen.

McConnell notes that one of the conversations was published in the magazine Psychology Today not long ago.

Runkel is presently a clinical psychologist working at the Winston C. Churchill Clinic outside London. This man, says McConnell of Runkel, is a psychotherapist par excellence.

Runkel notes that the public often treats police officers unfairly. For example, he says, if a doctor is accused publicly of misconduct, the majority of the public assumes that the doctor is innocent. If a policeman is accused of misconduct, the majority assumes his guilt.

Runkel has talked at length with both American and British cops. They very much alike, he says.

Professionally, says Runkel, American police officers are every bit as good as the Bobbies

Does Runkel have any suggestions as to how to improve the caliber of police departments? His answer should win him many more friends among police officers: They very much alike, he says.

I’m sure that if the salaries were at a more realistic level, he says, police departments would attract more first-rate men.

Runkel also believes that police should be given more diverse training, especially training in basic psychology, personality structure, and public relations. When I was at the police academy, he recalls, I tried to get them to read Dostoevski’s Crime and Punishment.

Runkel’s book is available from Planarian Press, Box 644, Ann Arbor. Текст публикуется по The Ann Arbor News Smile, says U psychologist; It’s good for you People who smile a lot tend to manage an office more capably, teach more effectively, sell more merchandise and raise happier children.

And they get more smiles in return. That alone is reason enough for smiling more, says University of Michigan psychologist James V. McConnell.

Imagine what life would be like if you never got feedback for your action or accomplishments. A smile tells us right on! Continue what you are doing! You are reaching your goal! McConnell says.

A FROWN ONLY tells us we’ve done something wrong, but seldom tells us what we should do instead to win a smile. There’s more information in a smile than a frown, McConnell says. Thats why encouragement is a much more effective teaching device than punishment.

His comments were made in response to a letter received by the U-M. The letter writer asked, What is the value of a smile? How does a smile, given and received, enrich our lives? How can we learn to smile more often?

McConnell does not claim to be an expert on smiling, but he does know its effect on people. We smile at others when they please us, because we absolutely need to be smiled at when we do something right. We can’t see ourselves behave, so we act as mirrors for one another. It is the Golden Rule all over again.

IN HIS INTRODUCTORY psychology classes, McConnell has taught people to smile simply by asking them to count the number of times they think they are smiling in a 10 minute period. Then he asks them to increase that number by one or two smiles during the next 10 minutes, and plot the results on a graph. |